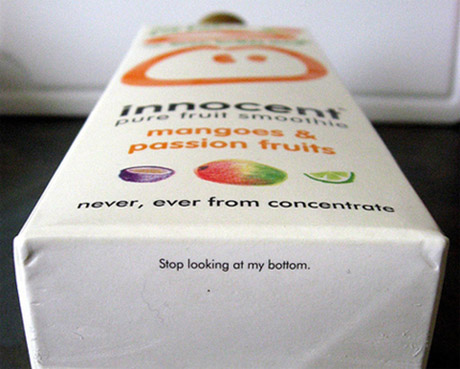

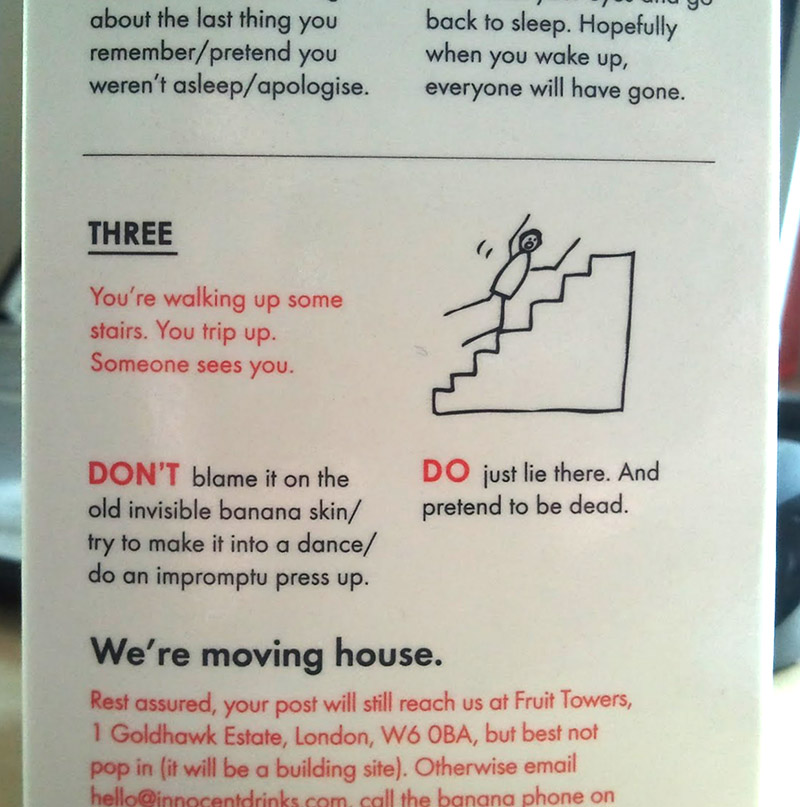

IMAGE: Innocent wackaging via.

If you’ve bought juice, crisps, cereal bars, soups, “breakfast pots” (porridge, as was), or any number of other ready-to-eat packaged foods in the U.K. this millennium, you may have noticed that your snack fancies a chat.

“British food packaging now has a matey, at worst babyish, tone that simply didn’t used to be there—commonly, food is describing itself in the first person,” explained an unimpressed Sophy Grimshaw, writing in The Guardian in 2014. “My basket of groceries now addresses me as though we are killing time on Facebook.”

This phenomenon has a name: wackaging, coined by journalist Rebecca Nicholson. Nicholson launched a tumblr to collect examples of the form in 2011, with the tagline “I blame Innocent smoothies.”

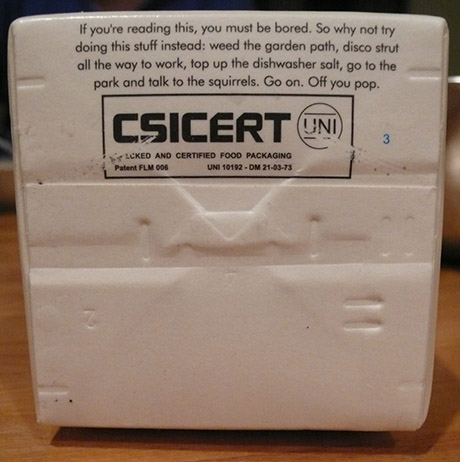

IMAGE: Innocent wackaging via.

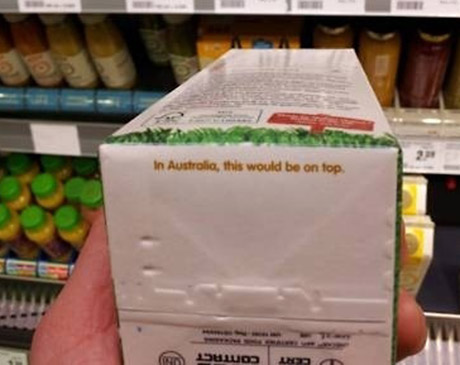

IMAGE: Slightly blurry Innocent wackaging via Buzzfeed.

An interview with Innocent Drinks’ co-founder, Richard Reed, in today’s Observer confirms Nicholson’s suspicions. In a Q&A, Reed describes founding the company in 1999, with his “two closest mates,” outlines his philosophy of success, and confesses to the wackification of British packaging.

Is it true you were personally responsible for “wackaging”—the quirky labels that are now everywhere?

Yes, that was part of my beat. I do think, oh my God, will my long-term contribution to the species be that I was the guy who introduced really annoying body copy on packaging?

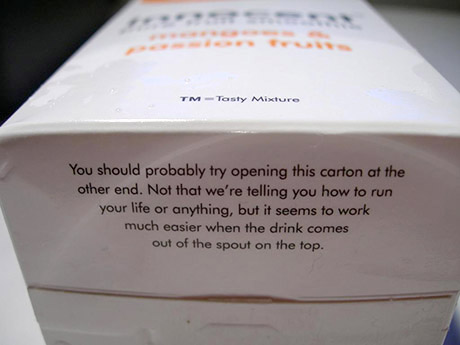

IMAGE: Innocent wackaging via London Copywriter.

The standard media reaction to wackaging seems to be a pained grimace: for The Independent it triggers “a cute sense of irritation” at being treated “like idiots or children”; Buzzfeed’s listicle on the subject is headlined “16 Enraging Examples of Cutesy Packaging”; and Grimshaw concludes her article with a despairing plea, “Let’s please stop before ‘store in a cool, dry place’ becomes ‘I love it in the cupboard!'”

I, on the other hand, have quite a soft spot for it—a sentiment that is only increased by learning the inspiration behind Innocent’s labeling copy:

Was it an Innocent innovation?

If we can make one claim, we can make this—that was new. I’ll tell you where it came from: have you seen Kingpin?The tenpin bowling movie with Woody Harrelson? Of course.

Well, there’s one scene, it’s not an integral scene, where somebody goes round to somebody else’s house and says: “Oh, I’m desperate for a dump, have you got anything to read on the toilet?” The guy looks around and passes him a bottle of shampoo and he looks at it and goes: “No, I’ve read this one already.” That’s where the idea came from.

IMAGE: Innocent wackaging via.

This revelation raises a couple of thoughts. Firstly, might Dr. Bronner’s be true progenitor of wackaging? And, secondly, given that the rise of smartphones over the past decade has taken care of any possible bathroom- (not to mention commute-, kitchen table-, supermarket queue-, solo dining-, etc.) reading material shortage, why has wackaging become so ubiquitous during the same timeframe?

IMAGE: Reddit user IRONFIRE.

The answer, I think, lies in seeing wackaging as simply a novel and perhaps peculiarly British chapter in the long story of packaging’s efforts to engender trust in an era of mass production. As I’ve written before, on the subject of butter packaging, the widespread decline in personal knowledge of food producers from the end of the eighteenth century is reflected in the simultaneous rise in packaging design that attempts to fill that gap.

As Gary Cross, co-author of Packaged Pleasures, explained on a recent Gastropod episode all about the history and science of packaging, the first labels promised a sanitary, standardised product—a cereal or cracker you could trust by virtue of its being made by machine.

More recently, as consumers have begun to mistrust “industrial” food, and sought instead to know where their food has come from and who made it, label copy has provided carefully edited personal stories and (frequently fake) geographies.

Seen in that light, wackaging is simply another iteration in this long shift from trusting people, to trusting institutions and companies, to trusting people again—a change that is playing out across society, not just in terms of food.

The difference, of course, is that if I had bought squashed fruit before the Industrial Revolution, I would likely have known the person who grew it; today, my only acquaintance with Richard Reed and his friends is through their label copy and media presence. In a way, Reed is like an online friend: the labels aim to communicate that same sense of knowing someone that you get from following the Twitter feeds of people you’ve never met, a technologically mediated kind of intimacy that is still real in its own way. Indeed, if packaging is a form of literature, wackaging is the social media equivalent.

Today, though, Innocent Drinks is ninety percent owned by Coca-Cola, a company that is synonymous with the industrial food system. Wackaging is simply part of Innocent’s brand now, rather than being any kind of personal connection to the people who made your smoothie. And corporations, despite the opinions of the U.S. Supreme Court, are not people. That, combined with its ubiquity, likely spells wackaging’s eventual demise, its authenticity eroded beyond belief. Enjoy those quirky labels while you can!