Although this week’s Glass House Conversation on the pros and cons of public investment in food design R&D has now closed, the questions and responses it has raised are well worth continuing investigation. The interview below, with PepsiCo’s Senior Vice President of Global Health and Agriculture Policy, Derek Yach, is a longer version of one published on GOOD yesterday, and I have a handful more Q&As on the subject to come. If you didn’t get a chance to say your piece over at the Glass House Conversations site (or even if you did—for which, many thanks!—but have more to add), you are very welcome to jump in in the comments.

IMAGE: Pepsi vending machines photographed by Michael Fillon.

As I mentioned over at GOOD, earlier this year, PepsiCo committed itself to reducing the salt in some of its biggest brands by 25 percent by 2015, and reducing the amount of added to its drinks by a similar amount by 2020. This is a fundamental redesign of foods and beverages that are a daily part of most people in the developed world’s diets (for better or for worse), and it requires a significant corporate investment into food design R&D.

Many of you will think that investing millions to make fizzy drinks and crisps “less bad” is not the way to go, and that the money would be better spent subsidising fruit and vegetable production, building urban farms, fixing school lunches, or any one of a number of possible options for improving the food system.

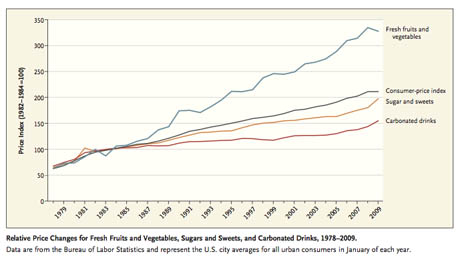

There’s also a strong argument to be made that if PepsiCo cared more about public health than profit, they would not spend so much money opposing the taxation of soft drinks (Kelly Brownell of Yale University’s Rudd Centre for Food Policy and Obesity has estimated that a penny-per-ounce excise tax would reduce consumption by ten percent; PepsiCo’s CEO says such a tax would “hurt the relationship between business and government” and hinted it might move its headquarters out of New York when a soda tax made it onto the state’s electoral ballot earlier this year).

IMAGE: Price changes over time for fresh fruits and vegetables (in blue) and carbonated drinks (in red), pulled from “Ounces of Prevention — The Public Policy Case for Taxes on Sugared Beverages,” by Kelly Brownell in the New England Journal of Medicine.

For myself, I wholeheartedly support soft drink taxation (although making such decisions at the state level, as tends to happen in the U.S., leads to all sorts of stupid inefficiencies). I also believe that food system reform is not a zero-sum game, and that grassroots activism, education efforts, policy changes, social justice initiatives, and corporate R&D all have a part to play in making the food that we as a society consume both healthier and more environmentally sustainable. Even if you never eat crisps and wouldn’t dream of drinking a Pepsi, enough people do both on a daily basis that any investment in their redesign has an enormous potential for impact on public and environmental health.

In any case, pre-emptive defence aside, Yach is a fascinating interlocutor. His background is in public health, including a stint at the World Health Organisation in charge of developing the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and the Global Strategy on Diet and Physical Activity. Our conversation ranges from the use of satellite imagery to redesign agricultural systems to the challenge of bringing new, niche products to market within PepsiCo’s gigantic global distribution system.

•••

Edible Geography: How is PepsiCo thinking about using food design to achieve its goals in the U.S., and also globally?

Derek Yach: The first issue for a discussion like this is how you define the boundaries of design, because you could say that design starts from the ground up. Landscape design has implications for the structure of agriculture, which has implications, based on its relationship with the environment, for the diversity of the food supply that we’ll have in the future.

From there, there are design features all the way along the line, from the science-based issues around plant breeding or transgenic modification to achieve specific nutrient changes, all the way up to packaging and processing.

Starting at the highest level, we are increasingly thinking about non-competitive issues between food and agriculture companies. I’m referring to agriculture-environment interactions, with a particular focus on asking some of the tough questions about how we are going to source the commodities that are going to go into any food product ten, twenty, or thirty years from now. What are the constraints we are going to face, where are the real opportunities, and where does the food that’s currently being grown actually end up?

When you start looking at that level, you realise that we have actually designed a food system that may not be providing the best nutritional impact. The assumption has always been that agricultural activities lead seamlessly into improved nutrition. We now know that’s not the case. There are many examples of large-scale agriculture that may be doing very well in producing—for example—livestock feed, which feeds animals that form part of a relatively small number of people’s diets, and don’t necessarily have the most desirable long-term impact for the individuals themselves, for society, or for the environment.

I mention that because it’s in sharp contrast to the subsistence farming reality of much of sub-Saharan African or India, where much of the food grown goes more directly into the mouths of people. Somehow we need to figure out the best advantages of both of those systems.

IMAGE: Agricultural landscapes photographed by the Terra satellite, via National Geographic. From left to right, top to bottom: Minnesota, Kansas, Germany, Bolivia, Thailand, and Brazil.

The U.S. system has been good at ensuring that there’s no hunger in America, by and large, and it’s been good at providing basic nutrients in a safe, secure way, by and large, for many decades. But now people feel that it isn’t providing the diversity in the diet that’s needed, and that the limits of environmental resources are coming up very rapidly, and we’re going to have to rethink a lot of this at the systems and process level. That means a complete shift to the way we’ve been approaching landscape design, recognizing that by far the biggest impact on the landscape comes from agriculture.

There is fascinating work being done, for example, at the Global Landscape Initiative, which is run out of the University of Minnesota by an astronomer who started turning the telescope down on earth. He’s developed these extraordinary different ways of using satellite imagery to analyse how agricultural land is used, from the U.S,. with its very large scale monocultures, to Europe, with its much smaller scale, more diversified farms, to the highly terraced activities of the Philippines, for example.

What does each of these systems mean for the sustainability of the agricultural endeavour, long-term, given water scarcity and climate change and all of these other things? And, more fundamentally, is the endeavour having the desired nutritional benefit? It’s kind of shocking to think that here we are in the twenty-first century and many of the studies looking into the relationship between agriculture and nutrition are concluding that the relationship is not necessarily all positive.

You might say: What is a food company doing, worrying about that? The reason is that we know, from our own scenario work and from our work with colleagues at Forum for the Future, that water scarcity is going to dictate where and how you can grow which crops, and increasingly we will all be required to think very carefully about the nutrient value as well as the financial value of those crops. Are we using scarce resources in the best possible way? These sorts of questions are at one end of the design spectrum.

On the other end of the spectrum, food design, when applied to altering particular nutrients, has been going on forever. I would say that food design in that context is more akin to cooking. The vast majority of our processes at big food companies can be seen as giant cooking exercises, being done in a more sophisticated, more rapid, and higher volume way.

IMAGE: Frito-Lay plant in Modesto, California, where PepsiCo installed solar concentrators in 2007. Photo by Peter DaSilva for The New York Times.

Every aspect of these processes are now coming under greater scrutiny, to see whether they can be redesigned to provide environmental or human health benefits. Decades ago, it didn’t seem important to worry about the type of oil that we were using, or the type of salt we were using, or even where the flavourings come from.

Now, we’re looking very carefully at all of those things, and finding that we can produce a healthier product by changing from saturated fats to a healthier sunflower oil, or even give heart-healthy advantages to an oil. We’ve come up with ways that we can give people a perception of saltiness without them consuming sodium at levels that they wouldn’t want to have in their bodies. These are some of the design issues to come out of the product.

The most important thing on the product design brief, though, is that it needs to taste good. We wouldn’t want to do anything that’s not going to taste good. There’s research going on now that is allowing us to learn a lot more about taste, so that we have more flexibility to redesign a product so that it’s acceptable from a health and nutrition point of view, and yet still tastes as desirable as it did in the first place.

PepsiCo was really the first big multinational to have very clear nutrition criteria for just about every product line. Some of them we’ve made public in our goals and commitments, and they translate into an enormous effort in redesigning our food processes.

When you take sodium out, it’s not just a question of just dropping it and keeping everything else the same—you’ve got to balance the seasoning, the flavourings, and everything else. When you change oils and fats, you have to actually change your whole agricultural procurement program. Getting hold of healthy oils often means partnering with development agencies to start growing programs, which is something we’re doing in Northern Mexico with sunflowers.

On the sugar side, which is obviously a big issue in our beverages, we’re having to develop new technologies to measure and detect natural sweeteners. Then when we find them, as in the case of stevia, we have to ensure that enough stevia is being grown to provide us with a product line.

The point in the process where people are probably most conscious of design is in the final product, in terms of its packaging and marketing. That’s an area where we’ve made great progress and we’ve made a few mistakes. You probably saw the SunChips story, where we designed for sustainability by creating a package that would decompose within twelve weeks in the ground. The only problem was that it made an almighty noise when you opened it.

In any case, these are just a few examples of how PepsiCo thinks about the relationship between design and food.

IMAGE: The SunChips compostable bag. Though complaints about its noisiness were funny (44,000 people joined a Facebook group titled “Sorry But I Can’t Hear You Over This SunChips Bag”), the fact that they were sufficiently damaging for Frito-Lay to switch back to non-biodegradable packaging was one of the more depressing news stories of the year.

Edible Geography: What is it that you think a transnational corporation is better positioned to do, in terms of redesigning food, than a government or individuals, and what should it be responsible for doing?

Yach: It starts with asking: What is the underlying value of companies and what’s their responsibility in society? The reason that I’m happy to be at PepsiCo is that our CEO and our chief legal officer asked a very simple question, “What is the legal responsibility of a company to sustainable development?” Not the moral or ethical responsibility—that, we know, is obviously very important—but what is its legal responsibility?

They’ve disagreed with Milton Friedman’s approach, which says that the primary responsibility is shareholder return in the short term, and concluded that because as a corporation, we’re given our license to operate forever, we have a legal responsibility to make sure that we are stewards of the environment from which we source our products from, and to make sure that we are also doing the best we can do in terms of the health of consumers, since they are the future consumer base of the company.

For legal reasons, there’s an increasing body of evidence building up that engagement in environmental sustainability and human health sustainability are a must-do, built-in component in businesses. That’s why things like the Dow Jones Sustainability Index or the Global Reporting Initiative are starting to take off. In time, I would suspect, companies will be judged as much by their sustainable development program as well as by their financial performance.

Once we’ve said that, it immediately translates into our roadmap for what we should be doing as a company. We should be ensuring that we source resources in the most sustainable way, which deals with water use, energy use, packaging, and agricultural supply. We should be aiming to increase the level of health and nutrition in our products across the board, and we should be ensuring that we market and sell those products to people in the most responsible way, which relates to marketing code and also to what we place in schools.

For example, one of our goals is that by the end of next year, we will have eliminated the direct sale of full calorie beverages from all schools worldwide. That’s not because we believe there’s something inherently wrong with those products, but because we believe that children need to be given a more diversified set of options in the school environment, and that school is a particularly important environment where kids learn their future food patterns. These are the things I think we should be and are doing to reshape the business.

Having spent time at the World Health Organization, what struck me coming into business is that the incentive systems for us to do the right thing are often not aligned the way they should be. So, for example, governments and consumers want us to do a lot more to lower sodium consumption and increase consumption of fruit and vegetables. You could take those two and ask: If government was a good partner, what would it be doing to make it easier for companies to do the right thing for business and society? On the sodium side you’d expect that there would be a large investment in the noncompetitive research required to lower sodium across the board, whereas in fact there is virtually no funding in that area.

They could also be doing a lot more to advise populations about the value of sodium reduction—even just when added to the meal. In fact I’m not aware of any major programs, outside of places like the U.K. and maybe Japan and Finland, that take salt seriously.

On the fruit and vegetable side, you’ve probably seen Michelle Obama and many others calling for increased fruit and vegetable consumption across the U.S.. The reality is if people were to consume at the level that she wants, the U.S. would have to double its acreage of agricultural land and government would also have to think very carefully about how it places the agricultural subsidies to shape what farmers grow.

At this stage, there’s discussion about these things, but there isn’t the kind of progress here or around the world that align the call of government for healthy diets and healthy eating and the incentives to make it easier for companies—not just ourselves, but even small or medium enterprises—to make that happen.

That’s in sharp contrast, I would say, to the way government and the pharmaceutical industry interact. There are many incentives for the pharmaceutical industry that don’t exist for food. The National Institutes of Health, which funnels $30 billion dollars of public money into basic research, is, you could argue, doing the non-competitive research that allows pharmaceutical companies to then innovate off a base of good, solid, basic science. That doesn’t exist for the food industry.

IMAGE: Lunch, photographed by CarioftheValley.

Edible Geography: What do you think is stopping government from incentivising non-competitive research and from realigning the subsidy program?

Yach: I’ve always thought that the path to policy change tends to come from academia first, with good, grounded science, which eventually seeps up into the policy environment. Obviously that takes time, and that’s why, I think, that we are in the position that we are with pharmaceutical approaches.

The past few decades have seen very successful growth of medical schools, a great deal of high quality science, and many breakthroughs—none of which we have seen on the agriculture, plant, and nutrition side. It’s very easy to point blame at any one or two people or institutions, but I think the real problem is the general neglect and underinvestment in agricultural research and the interface between agriculture and nutrition that we’ve seen since the seventies.

What has happened over these last few decades has been the growth of dependency on a subsidy structure that was created to ensure that nobody starved in America, as opposed to our current focus on how you can enhance nutrient quality and diversity in America.

We are seeing signs of this changing quite dramatically in terms of U.S. foreign policy responses. So, for example, three big initiatives that the Secretary of State is introducing globally are starting to roll back this lack of investment. The first is a very serious commitment to agricultural research in developing countries, partnering with U.S. institutions. This represents probably the first serious effort to invest since the seventies. At that time, the feeling was that the Green Revolution was starting to take shape and the need for the public investment in agriculture and agricultural science was now over. Investment in agriculture collapsed from twenty percent of foreign aid to under four percent within a couple of decades, and it’s only now starting to recover.

The second initiative comes from the recognition that investments in nutrition have economic value for societies long term. The State Department’s “1000 Critical Days” initiative, focusing on the first thousand days between pregnancy and age two, is based on an increasingly shared recognition that the nutrient quality of a kid’s intake until age two determines their intellectual and economic development at age thirty. These are relatively new insights, but they have enormous implications for economic development.

The third effort has been a willingness in the State Department to move away from a very strong focus on shipping food from the U.S. to aid-needing countries, toward now allowing local procurement of local commodities, by transferring funding and the capability to purchase. Those three things together, from an international perspective, are starting to correct some of the neglect. Provided they are accompanied by investments in institution-building and capacity, and a private-public perspective on how they could work together, I think they’ll have a big impact.

In the U.S. it’s always going to be tougher, given the political realities and complexity in this country. I don’t think it’s farmers who are resisting change. I think they would support a realignment of incentives that moved them toward diversified crops and a stronger focus on nutritional quality, provided it was sold to them in an incremental way. The thing about farming is that it’s a very long-term endeavor, often intergenerational, and you can’t change people from one crop to another and expect that you’re not going to have serious dislocation.

Edible Geography: If you were in charge of reshaping government spending and policy, at least in the U.S., how would you go about investing in non-competitive research?

Yach: I’d probably recommend taking a narrow perspective and focusing on the big challenges that we face on the food side—not the agriculture and plant side, because I think there’s a broader set of issues there. On the food side, I think the two priorities are lowering sugar in beverages and lowering sodium across the food supply. Of course, alongside them, a lot of marketing things need to happen—consumer education, smaller portion sizes, and so on. But sodium and sugar specifically lend themselves to an NIH-type of investment in a wide range of approaches that bring together the cutting-edge knowledge we now have on taste, flavour, and texture.

There’s spotty research going on inside the National Institutes of Health on this, but the tendency there will always be to move towards a medicated solution—to develop a pill for whatever ails us. There isn’t a sense of how we could generate food-based solutions. I’d want to see public investment in the basic science on the range of natural sweeteners, and more research into the different means of enhancing certain tastes. There’s been an explosion of research in the area of taste and flavour recently, and I think that science needs to be harnessed as we try now to address these two particular issues: sodium reduction and transforming the sweetness issues in our food supply.

IMAGE: Salt crystals, via.

Edible Geography: What, specifically, is the benefit of having that research happen in a publicly-funded environment, as opposed to individual corporations simply pursuing it in-house.

Yach: I think there are two benefits. First of all, I think it speeds up the process. We have seen how a mixture of private investors and public investment generates a sort of healthy competition. Look at the race for the human genome, for example. In the end, the NIH and the Wellcome Trust got there slightly ahead of the private sector, and the whole process established a cadre of people.

The second big benefit is that what comes out of basic research funded by the public sector is licensed in the public domain. Publicly-funded research has this benefit of equalizing the playing field for everyone and then allowing, for example, PepsiCo and Coke to compete at a higher level on the applied research and the product design—how you get to have great tasting, calorie-reduced products in the twenty-first century, which are also going to help you live to 200, or whatever else the added benefits might be.

It helps you move the shared baseline forward, basically. Have a look at statin development, as an example. The use of statins to lower cholesterol is ubiquitous now. Much of the basic science on statins was done by NIH grant, financed by the public purse. That then started the pharmaceutical industry competing like hell against each other for a variety of applications in the field, which is continuing to drive innovation today.

And we now have examples of consortia in the pharmaceutical industry, linking together the private and the public sector to try and tackle Alzheimer’s together, to accelerate the progress. Why can’t we have the same consortia approach of corporations partnering with the public sector to accelerate progress on sugar and sodium issues? I don’t think it’s beyond the possibility or even the interest of many of companies to do it. I think that what it takes is the recognition that a food-based approach to health is a more desirable route for the long term than a medication-based approach.

Edible Geography: I’d like to hear more about the process of setting priorities and goals. We’ve seen, for example, in Cancún, how enormously convoluted the process of trying to agree on goals for carbon emission reduction and climate change mitigation can get. What goes into setting goals and priorities in the world of food improvement?

Yach: We’re probably a lot more simple minded than the folk in Cancún. When I worked at the World Health Organization in Geneva, part of my task in developing the global strategy on diet and physical activity was to work with a team to figure out what, ideally, we would expect the private sector to do to improve the nutrient value of food. It actually wasn’t that complicated. We focused on reducing sodium, we wanted them to lower the calorie density and fats, and all of those things.

When I came to PepsiCo and we were looking at setting priorities, my business colleagues said, “Well, why don’t you start with what is already out there and agreed upon as the best means of improving population health.” So we made an identical list. And now every month that passes, another company pops up, joining us on one of our commitments. The latest was Nestlé, who recently joined us on sodium reduction. They’re doing 10% by 2015, we’re doing a much bolder reduction, but that’s nice.

I think that when you break things down to the specifics that you can take action on within your own business environment, it isn’t that tough to find what’s going to make the biggest difference. For me, I think the breakthrough was that the CEO and the senior executives of this company were willing to take targets that would have the biggest public health impact, regardless of whether it would be tough to do in business terms. It will become less tough as more and more companies join us.

Edible Geography: Finally, could you give two specific examples of food-design initiatives that have happened while you’ve been at Pepsi—one that has been a success and one where perhaps you’ve hit roadblocks that you weren’t expecting or constraints that limited your success?

Yach: One of the successes we’ve seen in the last eighteen months is Trop 50—Tropicana with 50 percent of the sugar. It went from not existing at all, through enormous internal resistance initially to idea of fiddling with the natural structure of orange juice, to now being a major multi-million dollar brand, growing very fast, and meeting the needs of people who want to have a good quality juice without the calories. On the food side, the expansion of hummus and chickpea-based programs has also been a great success.

On the less successful side, we launched True North, which is a fantastic range of nut and seed clusters that really has not grown as fast as one wants. I think that the problem was to do with the match between our distribution system, and what is a relatively small new product in this giant portfolio of ours.

The way that will be addressed going forward is that we are integrating of our bottlers into the business, which will give us much greater flexibility and allow us to take a wider range of smaller start-ups onto the shelves much faster than has been possible in the past.

I think the future will probably lie in a lot more flexible experimentation with products that will come and go depending on consumers’ likes and dislikes. Coming from a health background, I didn’t appreciate the critical role that distribution systems play. The beauty of PepsiCo is that we’ve got a whole range of them, all the way from very cold to long-life shelf life, in foods, beverages, and everything else.

[NOTE: If you’re interested in reading more perspectives on the possible benefits of redesigning food, and the role of individuals, governments, and corporations in shaping future food R&D, don’t miss this Q&A with Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art, as well as the many thought-provoking responses at the Glass House Conversation website.]