Historian Daniel Okrent’s recent book, Last Call, tells the story of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution — otherwise known as Prohibition.

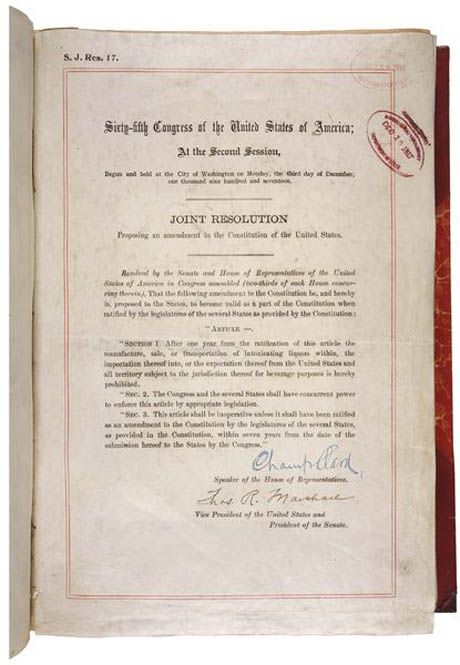

IMAGE: Constitutional Amendment XVIII, ratified January 16, 1919, via the National Archives and Records Administration. “After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.”

Although Prohibition lasted an amazing thirteen years — and though it did result in a drop in alcohol consumption (today, Americans drink roughly 60 bottles of beer less per person per year than than their early twentieth-century forebears) — Okrent concludes that:

In almost every respect imaginable, Prohibition was a failure. It encouraged criminality and institutionalized hypocrisy. It deprived the government of revenue, stripped the gears of the political system, and imposed profound limitations on individual rights. It fostered a culture of bribery, blackmail, and official corruption.

But it was an utterly fascinating failure.

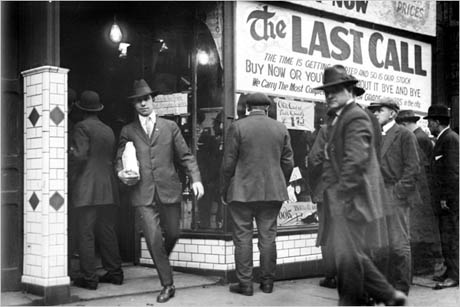

IMAGE: Detroit, the day before Prohibition. Photo from the Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, via the New York Times.

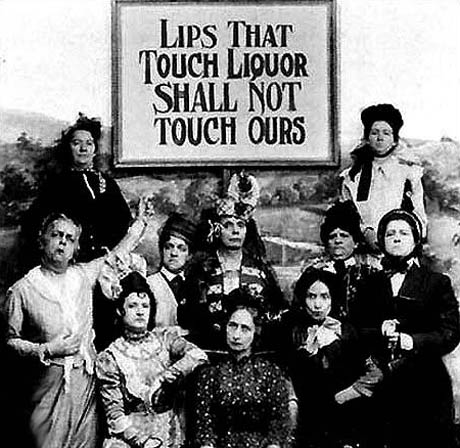

The first third of the book describes the unlikely constellation of social movements that enabled a country with an enthusiastic history of alcohol consumption — even the Puritans sailed to Massachusetts in 1630 with ten thousand gallons of wine in the hold — to outlaw its manufacture and sale outright. United under the dry banner were such unlikely partners as anti-immigration forces resentful of German brewing and Jewish distilling interests, racist Southerners dealing in stereotypes of “drunken Negroes who push white ladies off the sidewalks,” taxation progressives, and female suffragettes.

IMAGE: Without female support, such as that of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Prohibition could never have been passed. Photo via.

The First World War provided further momentum, pushing Prohibition over the edge at what was probably the last moment it could have succeeded. As Okrent points out, America was fast becoming an urban nation, and its cities were wet. Prohibition campaigners were grimly aware that:

Continuing immigration, the prolific birthrate of the largest immigrant groups, and the accelerating flight from the farms to the cities meant that by 1920, the urban population was almost certain to be a majority. After the constitutionally mandated decennial census, congressional districts would be redrawn […] “so as to absolutely insure for the liquor forces more than one-third” of the House.

IMAGE: Prohibition enforcement agents smashing barrels, via.

The rest of Okrent’s book describes the impact of Prohibition, in an extraordinary litany of unintended consequences:

In 1920, could anyone have believed that the Eighteenth Amendment, ostensibly addressing intoxicating beverages, would set off an avalanche of change in areas as diverse as international trade, speedboat design, tourism practices, soft-drink marketing, and the English language itself? Or that it would provoke the establishment of the first nationwide criminal syndicate, the idea of home dinner parties, the deep engagement of women in political issues other than suffrage, and the creation of Las Vegas?

In the first place, the laws drawn up to enforce Prohibition (the Volstead Act) were necessarily riddled with exceptions: for sacramental wine; for industrial alcohol (a necessary ingredient in the production of hundreds of everyday items, from pencils to flavour extracts); and for “the naturally occurring fermentation that takes place in some recipes for sauerkraut (up to 0.8 percent alcohol) and German chocolate cake (0.62 percent).”

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Prohibition, then, lies in the way these loopholes, combined with the immense fortune to be made from providing tax-free, unregulated alcohol to America’s thirsty drinkers, combined to create an entirely new geography of alcohol, reconfiguring homes, cities, agricultural landscapes, and even national borders.

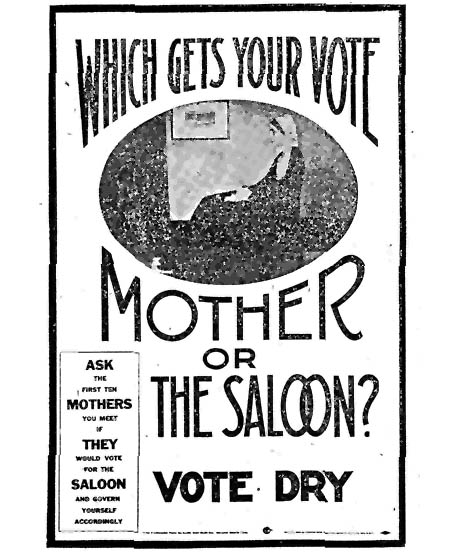

IMAGE: Anti-Saloon League poster, via.

In fact, the dry campaign made its spatial ambitions clear from the start: the largest and most important pro-Prohibition group was called the Anti-Saloon League. According to Okrent, at the turn of the twentieth century, there were nearly 300,000 saloons in the United States: one for every 100 inhabitants in Leadville, South Dakota (“women, children, and abstainers included”), and an astonishing 4,065 below 14th Street in Manhattan alone. In addition to shuttering all of these ubiquitous bars, the Anti-Saloon League and its supporters promised that the “death of liquor” would also mean that “the slums will soon only be a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs…”

IMAGE: Closing a saloon, via.

Chicago did close one of its jails, the first year after Prohibition took effect, while “diminished criminal behavior led Grand Rapids, Michigan, to abandon its work farm.” But the accidental spatial aftereffects of making the manufacture and sale of alcohol illegal were much more radical. As the Anti-Saloon League promised, “a new nation” was indeed born from Prohibition: diverting the flow of booze underground reshaped the physical and cultural landscape of America in ways no one could have imagined.

For example, the “fruit juice clause,” originally inserted into the Volstead Act to allow otherwise dry-voting country dwellers to continue making hard cider, converted America into a nation of wine drinkers.

During the California Grape Rush of the 1920s, wheat fields and fruit orchards across the Napa Valley were ripped up and replanted with vines, with the state agriculture agency reporting that “the acreage in grapes was ‘increasing by leaps and bounds since the enactment of the Federal Prohibition Law.'” As Cesare Mondavi and Joseph Gallo launched their Californian empires, American wine consumption increased from 70 million gallons in 1917 to 150 million gallons in 1925.

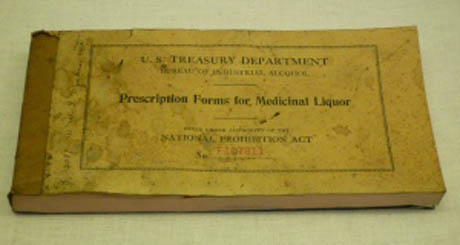

IMAGE: Prescription forms for medicinal alcohol, via the Rose Melnick Medical Museum.

Charles Walgreen of Chicago took advantage of another loophole in the Volstead Act, which allowed “the legal distribution of alcoholic beverages for medicinal purposes.” Walgreens’ official history credits the company’s rapid expansion, from nine locations in 1916 to 525 by the end of a decade of Prohibition, to the invention of the milkshake. Okrent, however, casts doubt on this version of events, noting that “the cash flow from few enterprises gushed with quite the velocity that Prohibition brought to the drugstore business.”

In addition to the proliferation of California vineyards and chain drugstores encouraged by Prohibition’s legal exceptions, the activities of bootleggers and smugglers actually prompted an international redrawing of maritime borders.

IMAGE: “A motorboat makes contact with liquor smuggling British schooner KATHERINE off the New Jersey coast to smuggle the booty ashore.” 1923; photographer unknown; photo courtesy the U.S. Coast Guard.

From early on, boats dropped anchor just outside the three mile limit of U.S. territorial waters, and “hung poster-sized price lists over the gunwales no more self-consciously than if they’d been selling potatoes.” By 1923, Okrent writes, “from the Gulf of Maine to the tip of Florida, an enormous fleet of old freighters, tramp steamers, converted submarine chases, and ships of various other descriptions […] lay at permanent anchor, […] immobile for months at a time, functioning as floating warehouses.”

Off major ports, this floating Rum Row, or “inverse blockade,” as Okrent terms it, took on almost urban proportions:

In many places nightfall unveiled a constellation of ship’s lights so dense, recalled a captain who serviced vessels anchored off Highland Light on Cape Cod, “you would think it was a city out there.”

This is an incredible image: a floating ship-city, thousands of miles in length, bobbing up and down in place along the coast of America, and serviced by a fleet of much smaller, nimble rum runners that slipped to and from the mainland under cover of night.

IMAGE: “Captain Byron Laverne Reed, USCG, Commander of the New York Division and Captain of the Port of New York, takes a group of Prohibition officials on board the USCGC MANHATTAN to observe the Rum-Row fleet, coast of New Jersey, in November 1924.” Photographer unknown; photo courtesy the U.S. Coast Guard.

The State Department countered by attempting to extend the demarcation line between national and international waters an extra nine miles, or “an hour’s steaming distance from shore.” Despite initial reluctance on the part of the British and French, whose winemakers and distillers were making money hand over fist selling to smugglers, and who despised Prohibition as “Puritanism run mad,” the U.S. succeeded in enforcing these new maritime borders — a global geopolitical realignment enacted purely on the basis of alcohol control.

Ridding the American landscape of its thousands of saloons also resulted, perhaps predictably, in the domestication of drink. The ’20s were notable, according to critic Malcolm Cowley, for the “invention of the party,” as Americans started to invite each other round for cocktails and alcohol-fueled dinner parties. Okrent even credits Prohibition with the rise of the mixer, as drinkers sought to mask the harsh flavour of industrially-produced alcohol.

Quinine water, or tonic, originally developed in India as an antimalaria nostrum, became a standard masking agent for gin of dubious origin. Ginger ale replaced soda water as the standard mixer for whiskey because its flavor could smother the laboratory odors of fake rye.

IMAGE: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Several of these cocktails were enjoyed in a more temporary spatial innovation in the American landscape (albeit one that is undergoing a contemporary renaissance): the speakeasy. While describing the various permutations these “hooch joints” could take, depending on the neighbourhood, Okrent adds a fascinating aside: several culinary historians “attribute the American fondness for southern Italian cuisine to the exposure it received” in the grappa-serving parlours of Italian rooming houses, “from Boston to San Francisco.”

Other temporary distortions to the built environment inspired by Prohibition included a string of “boozoriums,” or bottling and storage warehouses along the Canada-U.S. border, as well as hundreds of home stills, which in Chicago formed a “network so large the entire Near West Side reeked of alcohol fumes,” while canny Denver distillers “placed animal carcasses near their distilleries, thus disguising the telltale scent of sour mash with the more potent aroma of rotting flesh.”

IMAGE: Police with confiscated still equipment. Photo via Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

When prohibition was finally repealed in 1933, Napa Valley, Walgreens, and the expanded definition of coastal waters survived as Prohibition’s legacy (along with NASCAR, female voting rights, and a national taste for Coca-Cola). But many of the speakeasies, illicit stills, and cross-border smuggling infrastructure vanished — leaving little but criminal syndicates, vast wealth, and, in the case of the row houses adjacent to the legendary “21” Club in Manhattan, an “odor of alcohol that permeated the soil,” as reported by workers digging the foundations for a new public library branch in the 1950s.

In fact, for most Americans, it actually became “harder, not easier, to get a drink” after Repeal, as states enacted their own patchwork of closing hours, blue laws, and zoning regulations to restrict access to alcohol. These laws encourage their own spatial responses today, as towns on the Jersey side of the Pennsylvania/New Jersey border or the Wyoming side of the Utah/Wyoming state line boast vast discount liquor warehouses, complete with ample parking.

IMAGE: Prohibition protesters. Photo via Getty Images.

Okrent concludes Last Call by suggesting that perhaps Prohibition’s most lasting legacy is as an example.

In the past, it has been used to argue for abortion rights and against school integration. Today, it is most frequently invoked to argue for the legalisation of marijuana. But it is also a fantastic, if extreme, example of the way food and beverage policy can reshape the physical and cultural environment — both intentionally and not.

In other words, while Daniel Okrent’s stories of Prohibition’s impact on the American landscape make wonderfully enjoyable bedtime reading, they might equally well serve as both inspiration and caution to today’s urban planners and health policy makers as they attempt to redesign the geography of food.