A couple of years (!) ago, I mentioned that I would be working with the Center for Land Use Interpretation on an exhibition exploring the U.S. cold chain. I’m delighted to announce that the result of that collaboration, Perishable: An Exploration of the Refrigerated Landscape of America, is now on display at CLUI’s Los Angeles headquarters.

IMAGE: Birds Eye frozen food plant, Darien, Wisconsin. CLUI photo.

Regular readers will be aware of my ongoing refrigeration obsession, which I’m currently channeling into book form. As a long-time admirer of CLUI’s work, the opportunity to work alongside Matt Coolidge, exploring the national cold chain using the Center’s distinctive methodology was extremely exciting. We were lucky enough to secure a generous grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, which made the travel necessary to “ground-truth” each site (a crucial step in the CLUI process) possible.

IMAGE: CLUI’s understated exterior on Venice Boulevard. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: Perishable: An Exploration of the Refrigerated Landscape of North America installed in the diminutive CLUI gallery space. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

As is often the case for CLUI exhibitions, Perishable relies on a handful of video displays and interactive touchscreens in order to survey a vast geography in a space that is the same size as the average living room. For this show, however, the gallery is specially accessorized with insulating vinyl strip curtains and a “refrigeration tone,” sound-designed by George Budd.

IMAGE: Perishable: An Exploration of the Refrigerated Landscape of North America; photograph by Nicola Twilley.

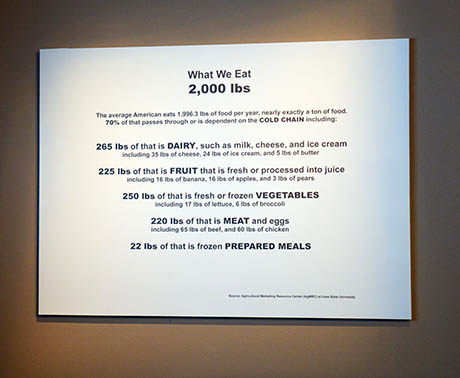

The exhibition begins by emphasising that the diet of the average American is almost entirely dependent on the existence of a vast, distributed winter—a seamless network of artificially chilled processing plants, distribution centers, shipping containers, and retail display cases that creates the permanent global summertime of our supermarket aisles.

IMAGE: At least 70 percent of the food we eat each year passes through or is entirely dependent on the cold chain for its journey from farm to fork, including foods that, on the surface, seem unlikely candidates for refrigeration. Peanuts, for example, are stored between 34 and 41 degrees Fahrenheit in giant refrigerated warehouses across Georgia (which produces nearly half of the country’s peanut harvest).

IMAGE: Three video screens divide the national coldscape survey into Produce (on the left), Meat, Dairy, and Processed Foods (in the middle), and Distribution (on the right).

Taking our cues from the contents of the American plate, we traced the most consumed foods back through the cold chain to their point of production or arrival, seeking out refrigerated sites that are either superlative or representative, or both.

In the banana’s case, for example, these include the largest ripening facility in North America (Coast Tropical of Los Angeles, which boasts fifty pressurized rooms), as well as the banana ports of Wilmington and Hueneme (Dole and Chiquita prefer these smaller ports, which specialize in perishable products and where delays are less likely, over their much larger and busier neighbors, Newark and Long Beach).

IMAGE: Tropicana, Bradenton, Florida; photograph by Nicola Twilley.

Meanwhile, the orange juice trail led us to Florida, where Tropicana’s Bradenton facility boasts the largest tank farm in North America, and thus also one of the continent’s largest refrigerated enclosures, at 29 million cubic feet.

Although Tropicana is the largest orange juice brand in the US, with 28 percent of the market, the largest orange juice company in the world, Citrasuco, is Brazilian. Their juice discharge and storage terminal at the Port of Wilmington boasts three 1.5-million gallon aseptic tanks for not-from-concentrate (NFC) juice, and twenty-four 265,000-gallon tanks for orange and apple juice concentrate.

IMAGE: The exterior of the not-from-concentrate (NFC) tank farm at Citrusuco’s dockside facility at the Port of Wilmington. A tiny Geoff and our guide Brian provide scale toward the building’s bottom right. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

Although the CLUI modus operandi typically restricts site documentation to exterior shots, I can never resist the opportunity to get behind the scenes, so here are a few extra shots of the Citrasuco facility from the inside, which are not in the exhibition.

IMAGE: Slightly smaller tanks house frozen concentrate at Citrasuco; the juice can stay frozen for up to two years. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: The hose trailer: “a beast to handle,” according to our guide. OJ is piped in these large rubberized tubes from the hold of specially designed refrigerated ships. This facility receives eight to ten shipments per year, and it takes three to six days to unload each ship. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: This mixing board allows Citrasuco to dial in the precise ratio of NFC juice to oil and essence to achieve the flavor profile required by each customer. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

Other highlights of the produce cold chain include strawberry giant Driscoll’s packing house in Watsonville, California, the Lamont, California, home of the world’s largest carrot producer, River Point Farms’ Oregon onion empire, and, of course, several coldscape hotspots for that king of vegetables, the French fry.

IMAGE: Billboard near the Simplot plant in Nampa, Idaho (top); Ore-Ida plant in Ontario, Oregon. CLUI photos.

More than 50 percent of the nation’s potato output is cut, processed, frozen, bagged, and distributed as French fries.

Idaho-based agri-giant J.R. Simplot Company, inventor of the industrial frozen French fry and McDonald’s largest supplier, is represented by two of its six frozen potato plants—the Nampa and Caldwell facilities. The air around them is thick with the smell of mashed potato, as they churn out frozen shoestrings, thin cuts, regular cuts, wedge cut, batter-coated, tater gems, and hashbrowns. Meanwhile, the primary plant for rival Ore-Ida, inventor of the tater tot, is just over the border in Oregon.

IMAGE: Albertson’s Southern California cold storage warehouse in Brea (top left); a Tyson Meats cold storage loading dock in Russellville, Arkansas (top right); Preferred Freezer Services refrigerated warehouse in Vernon, California (bottom left), and the sole source of Tofurky, in Hood River, Oregon (bottom left). CLUI photos.

Two additional screens offer similar tours of notable refrigerated facilities in the meat, dairy, and processed foods industries, and major hubs in the distribution cold chain. These range from the predictable (Tyson’s beef-packing plant in Amarillo, Texas), to the unexpected (Advanced Fresh Concepts, in Compton, CA, is the largest sushi provider in the United States), via mega-dairies (also in Compton) and TV dinners (such as the Russellville, Arkansas, ConAgra plant that makes frozen entrees for the P.F. Chang’s brand).

Stops on the distribution cryo-tour include the headquarters of C.R. England in Salt Lake City, home of the nation’s largest fleet of “reefer” trucks, the new Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market, which boasted the largest central refrigerated system in the United States when it opened in June 2011, and, of course, the 3 million square feet of former limestone mine operated by America’s largest cold storage company, Americold, in Carthage, Missouri.

IMAGE: Carthage, Missouri, whose already cool underground storage chambers are made even colder by refrigeration plants located on the surface. The former limestone mine is a popular excursion for urban explorers, who go boating and spot turtles on the flooded lower levels. CLUI photos.

A final screen is devoted to the external architectural clues that point to a thermally-controlled interior, of which the most noticeable is the orange wind sock, visible at all cold storage and food processing plants where ammonia is used as a refrigerant, so that in case of an accidental leak, employees can head upwind.

The one element of the exhibition that also lives online is a touchscreen map, with pins representing a selection of refrigerated sites around the country.

IMAGE: This interactive map lives on the CLUI website.

The geography of cold, for the most part, traces the curious logic of the food industry.

In the case of fruit and vegetables, meat, dairy, and fish, refrigeration often maps onto production. In other cases, it is aligned with transportation nodes—for example, a logistics hub near Allentown, Pennsylvania, where U.S. Foods, Americold, Millard Refrigerated Services, Kraft, Ocean Spray, and others all maintain facilities, owes its popularity to its location at the intersection of I-78, I-476, and several East Coast railway lines. It is also close to major urban markets in the north-east corridor—but not so close that the land is expensive. City officials in such areas often compete for warehousing business: the city of Vernon, in California is notorious for charging rock-bottom rates for its utilities, and boasts block after block of cold storage.

IMAGE: A visitor explores the coldscape using the touchscreen map; photograph by Nicola Twilley.

As an exploration, rather than a survey, the exhibition and associated map are selective rather than exhaustive. It is, apologies for the pun, merely the tip of the iceberg. Instead, we tried to offer a selective but representative overview of the distributed winter in which we house our food, in all its geographical logic and architectural variety, and, in so doing, shed light on the overlooked infrastructure of thermal control that underpins the way we eat. I hope you enjoy it.

Perishable: An Exploration of the Refrigerated Landscape of America is on display until September 1, 2013, at the Center for Land Use Interpretation, 9331 Venice Blvd., Culver City, CA 90232. It is open from 12 to 5 PM, on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, or by appointment, and admission is free.

Although the exhibition is co-curated, Matt Coolidge is the genius behind its organization and presentation, and members of the CLUI corps, particularly Aurora Tang, Steve Rowell, and Jenny Lion, logged thousands of miles in order to document the sites on display. The exhibition was supported by a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, and I also owe thanks to Paola Antonelli and Joseph Grima for their support for our application. On my end, Geoff Manaugh has unhesitatingly accompanied me on many of my far-flung refrigeration expeditions (and will do so, I hope, on many more, despite the often unglamorous destinations and uncomfortable temperatures). Marissa Looby helped me wrangle U.S. consumption data to arrive at a solid set of statistics (never my strong point) for average annual consumption of various perishable commodities. An enormous number of cold storage plant managers have shared their time and expertise to show me around their facilities and explain their operations: I should single out Adam Feiges of Cloverleaf Cold Storage, in particular, for his generosity in helping me understand the nature of the business as a whole.