When Fuschia Dunlop, a British cook and food writer specialising in Chinese cuisine, was compiling material for her recent book on Hunanese food, she faced a difficult decision: to include, or not to include, a recipe for General Tso’s Chicken.

IMAGE: General Tso’s Chicken as served in San Francisco, via Flickr user Rick Audet.

For readers unfamiliar with the dish, General Tso’s Chicken consists of battered, deep-fried bits of chicken, coated in a spicy sweet and sour sauce. It is also the pad thai of Chinese food in America: broadly popular, guaranteed to be on the menu, and the single-dish shorthand for an entire cuisine.

As Dunlop explained during a lunchtime lecture at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) last week, the case against including General Tso’s Chicken in the Hunanese canon is persuasive. For starters, in Hunan itself, it is impossible to find either the dish or anyone who knows what it is.

IMAGE: Chinese man encountering a fortune cookie for the first time, from Jennifer 8. Lee’s TED talk. As she demonstrates, baffled curiosity is quite a common Chinese response to the American version of Chinese cuisine.

There was another problem with including General Tso’s Chicken in a regional cookbook: it doesn’t taste anything like typical Hunanese food. Hunan (or Xiang) cuisine is one of the eight traditional schools of Chinese cookery, known for its distinctive dry heat, and sour, salty flavours. General Tso’s Chicken, on the other hand, not only uses larger chicken pieces than are typical in Hunan cuisine, but is also deep-fried (not a typical cooking technique in the region) and is far too sweet for Hunanese palates.

Nonetheless, and despite the weight of evidence against it, not including General Tso’s Chicken in one of the first English-language books solely focused on the cuisine of Hunan seemed, in Dunlop’s words, “a little perverse, given that it’s the only dish most people know from the region in the first place.”

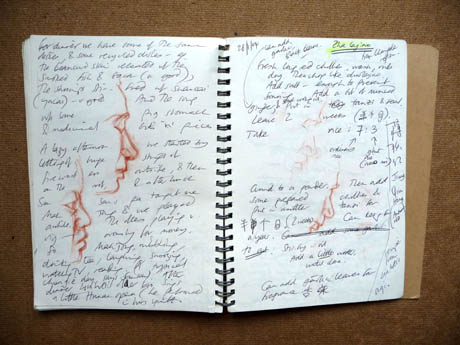

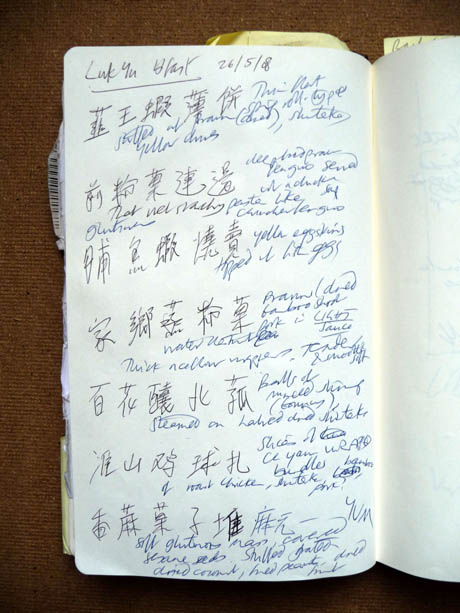

IMAGE: One of Dunlop’s notebooks from her research in Hunan.

More interestingly, Dunlop went on to claim that in some syncretic way, General Tso’s Chicken actually tells a compelling story of place that can’t be found in the more traditional Hunanese hot pots, steamed fish heads, and smoked bean curd – although uncovering that story required a fair bit of detective work.

China’s Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward (with its subsequent famine) were a “culinary disaster,” explained Dunlop, during which traditional dishes and cooking techniques went underground or were lost altogether. Restaurants were nationalised, the quality of produce nose-dived, apprentices were encouraged to denounce master chefs, and fine dining restaurants were expected to forget the grand Mandarin tradition and serve plain, hearty food for the masses.

Although Mao was himself from Hunan and traveled with a personal chef from the region, he preferred traditional peasant dishes that were ready in twenty minutes or less. Meanwhile, the elites of the Kuomintang, for whom eating well was one of the accomplishments expected of an educated man, retreated to Taiwan with their chefs in tow.

And Taiwan is where Dunlop eventually found the original General Tso’s Chicken, or at least its close relative, Viceroy’s Chicken.

The dish was a little less sweet than the American version (it used tomato paste rather than sugar – Dunlop’s version of the recipe is here) and it had been on the menu at Peng’s, a restaurant specialising in Hunanese cuisine, since the 1950s.

IMAGE: Peng Chang-kuei and Fuschia Dunlop in Taipei, in 2004.

The restaurant’s owner told Dunlop that the dish was created by his father, Peng Chang-kuei, who had originally learned to cook in Changsha, Hunan’s capital city, as an apprentice to the celebrated and classically-trained chef Cao Jingchen. When the Nationalists fled to Taiwan in 1949, Peng accompanied them – along with talented chefs from all over China.

Peng soon began preparing traditional Hunanese dishes for government banquets, as well as at his own restaurant. In 1973, he then moved to New York City to open another eponymous restaurant, adjusting his fusion-inflected Hunanese to suit American palates. The restaurant was a critical success – incredibly, Henry Kissinger was a regular customer – and Peng’s version of Hunan cuisine was replicated across America, becoming the “official” version despite its two-step mutation.

IMAGE: One of Dunlop’s notebooks from her research in Hunan.

The final twist to Dunlop’s tale involves the adoption of General Tso’s Chicken – this hybrid dish of civil war and exile – by a new generation of celebrity chefs from Hunan, some of whom were even trained by Peng during his brief visits to the gradually opening China of the 1980s.

Doubtless, these chefs were asked about General Tso’s Chicken when they visited America for book tours or cooking demonstrations. Dunlop speculates that they claimed it as an authentic regional speciality – papering over the cracks in China’s recent culinary history rather than risk losing face by admitting that Taiwan was the source of Hunan’s most famous dish.

Many well-known dishes have names or stories that explain their origins. One common story in China tells of the emperor or king in disguise, visiting his people anonymously. At the end of the day, he goes into a restaurant to order a meal – but there’s nothing left. Nonetheless, the unsuspecting chef manages to invent some kind of dish out of the few ingredients he has left in the kitchen, the emperor (or king) finds it delicious… and so on. Attaching this story to a new recipe makes it seem somehow familiar – part of a culinary tradition.

The story behind General Tso’s Chicken, as Dunlop tells it, is more complex and less comforting. Nonetheless, it embodies many aspects of China’s twentieth-century historical and culinary (r)evolution: the traditional master chef/apprentice system, the nostalgia of exile, the promiscuous mixing and adaptation of diaspora, and finally, the opening of China and its new generation of celebrity chefs, eager to show off their regional cuisine to the world but uncomfortable dealing directly with their country’s recent past.

IMAGE: Billboard outside the real General Tso’s ancestral hometown, from Jennifer 8. Lee’s TED talk.

Finally, in case you were wondering, there is indeed a real historical figure called General Tso, but he preceded his namesake dish by nearly a century. Chef Peng simply chose to name his chicken concoction after this successful and admired Hunanese military and political leader from the Qing dynasty, perhaps to heighten its nostalgic appeal to his fellow exiles.