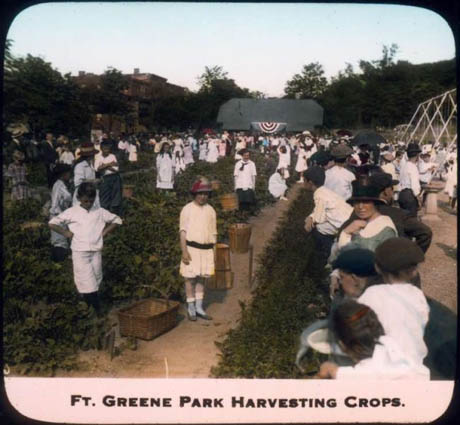

IMAGE: “Judging the fruits of a community garden as part of the Park Farm Contest.” Courtesy of Parks Photo Archive, Neg. 16092. Photo by Max Ulrich, taken at Thomas Jefferson Park, Manhattan, on April 4, 1939.

Despite the rise of rooftop and island farms, old-school community gardens are probably the largest component of urban agriculture in New York City today.

I say probably because, as Mara Gittleman, Compton Mentor Fellow at GrowNYC, told me, “No one knows how much food New York City’s community gardens produce.” In fact, no one knows for sure how many of them produce food, although she considers eighty percent, or about 400 gardens, to be a safe estimate. Until Gittleman spent last year surveying and visiting many of the gardens registered (and not registered) in Green Thumb’s database, no one even had up-to-date figures on the number of community gardens in the city, let alone how many were still active.

IMAGE: “The practical-minded administration of Robert Moses boasted of growing ‘plants of economic interest’ such as cotton, peanuts, flax, wheat, Indian corn, and ‘old-fashioned herbs’ at Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn.” Photo via New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

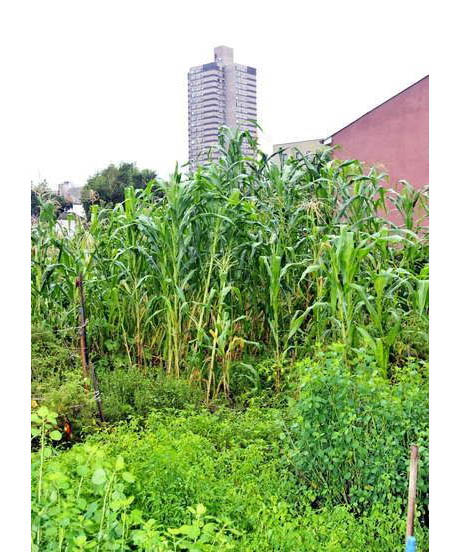

IMAGE: Garden Of Happiness, Bronx . Photo taken by Malcolm Pinckney on September 12, 2009, via NYC Department of Parks and Recreation.

This is a pretty amazing data hole, given the frequency with which New York City’s community gardens are invoked by city officials, activists, and urban planners as a solution to environmental, food security, and public health challenges, as well as a source of green-collar jobs. For example, City Council Speaker Christine Quinn’s FoodWorks New York initiative lists the expansion of “urban agriculture through community gardens” as a key goal, while Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer pledged to “support community gardens” in order to increase urban food production in his policy paper, Food in the Public Interest (pdf).

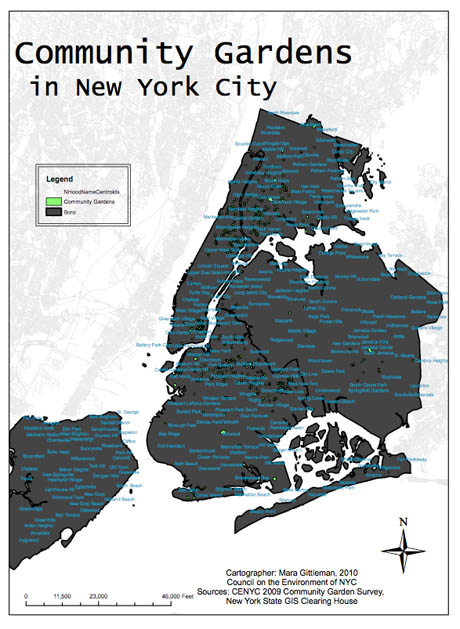

“When I got this fellowship and went to GrowNYC, the only community garden map that existed needed an update,” explained Gittleman, a recent Tufts graduate. “And it included schools and playgrounds and all these things that aren’t community gardens.” Before she could conduct any of her planned analyses of New York City community gardens—finding out which could act as public compost locations, for example, or correlating food-producing gardens with census data and supermarket locations—Gittleman spent a year updating the map, verifying whether gardens are still active, and filling gaps in the database.

IMAGE: Map showing community gardens in New York City, 2010, by Mara Gittleman.

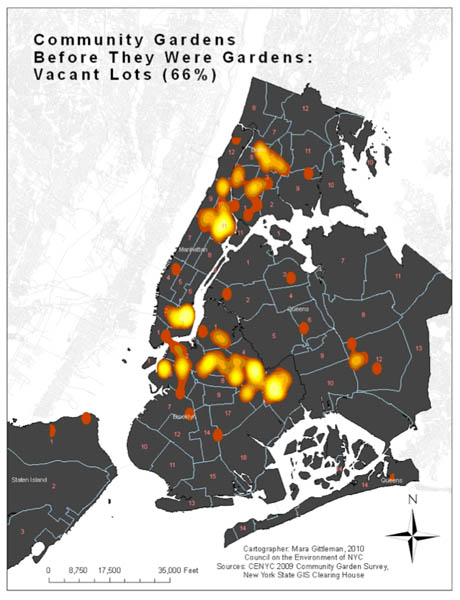

After survey mail-outs, phone calls, and lots of footwork, she arrived at a database of just under five hundred community gardens, of which at least one hundred and fifty were not registered or being tracked in any way. “There are four main concentrations of community gardens,” Gittleman told me. “Central Brooklyn, East Village, the Upper Manhattan/East Harlem area, and South Bronx. The neighbourhoods that that burned down a few decades ago, leaving all these vacant lots.”

IMAGE: Map showing community gardens that were previously vacant lots, 2010, by Mara Gittleman.

Her next project, Farming Concrete, begins this month: her mission for the rest of 2010 is to measure exactly how much food is grown in New York City’s community gardens, on how much land, and with what monetary value.

This is a much bigger undertaking than it might initially sound. According to Gittleman, “the only other time a project like this has been done before was in Philadelphia, last year, which was great, but they used a lot of estimates. My goal is to get these numbers as accurate as possible.”

To that end, Gittleman and her team of volunteers (of which more later) will map all of the areas under production within each garden, measuring exactly how many square feet are devoted to cultivating different foods. Then she will get a statistically significant number of gardens (at least two hundred, she hopes) to commit to weighing all their produce through the end of the season—every single tomato, squash, and sprig of thyme. Mournfully, Gittleman told me about the one exception to her rigour:

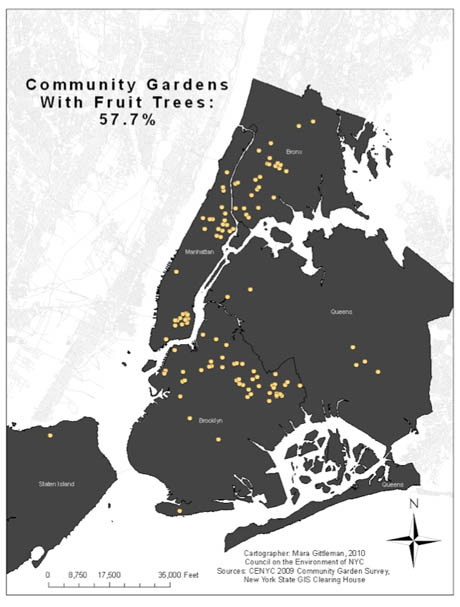

The problem with that is that we don’t get to include fruit trees, which is sad. First of all, the square footage of a fruit tree is really difficult. We can do poundage, but we can’t do entire poundage—the fruit at the top usually doesn’t get picked and some falls on the ground and in any case, nobody at a community garden is going to be willing to take on a fruit tree and weigh every piece of fruit that comes off it. All we can really do is count all the fruit trees and then use an estimate.

IMAGE: Map showing community gardens with fruit trees, 2010, by Mara Gittleman.

The average crop volume from the gardens that measure their harvest can then be extrapolated for the other gardens whose growing area has been mapped: the result will be a map of the area used for food cultivation, a total volume harvested for each crop, and its corresponding dollar value. Gittleman also plans to release her raw data-sets, as well as give “each garden a sentence that says, ‘We at Community Garden X produce X lbs of food for this many people in this amount of space. It’s worth this much money and it prevents this many lbs of greenhouse gas emissions from entering the atmosphere.'”

As a chronic shortcut-taker, I suggested that Gittleman might like to bypass the weighing stage and just rely on existing yield estimates. Her response was quite astonishing: despite all the interest and hype, it seems that there are no good numbers out there for the amount of food different plant species can produce when grown in an urban, community setting.

Of course, there are yield numbers out there for each crop—but they’re for commercial crop production, which is totally different from what happens in a community garden. The conditions, soil, treatment, and scale are just so different.

This kind of data will thus be enormously useful: just for starters, Nevin Cohen and the Design Trust will know what to expect from community gardens as they develop a city-wide plan for urban agriculture. “And,” added Gittleman, “down the line, if the city gets to this point, these numbers could help prove that urban food cultivation is viable and it does have an impact and it is worth something. It would go towards New York City’s climate change emissions and sustainability goals, and so on.”

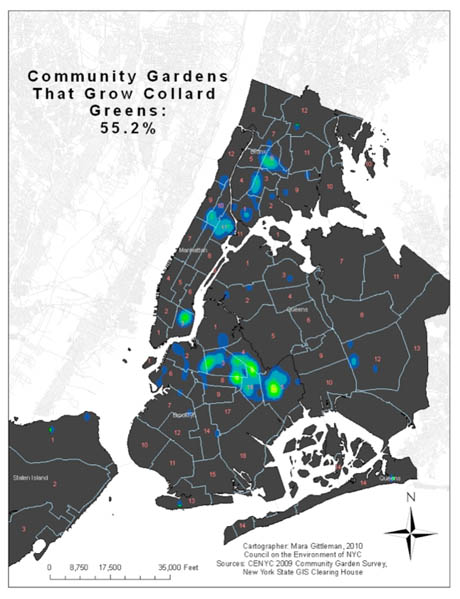

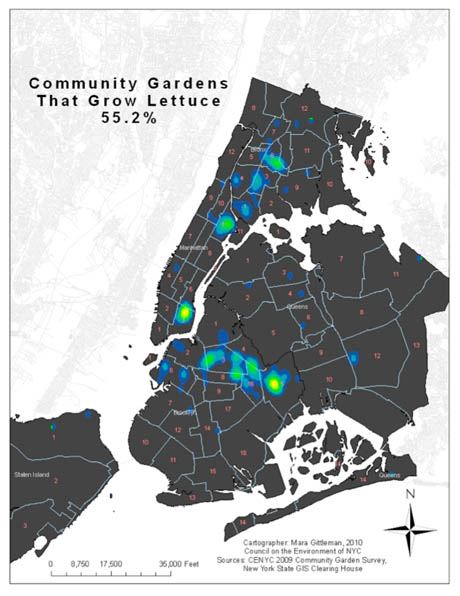

IMAGE: Maps showing community gardens that grow collard greens (above) and lettuces (below), 2010, by Mara Gittleman. Gittleman is a map enthusiast, and is currently working to combine the data on these separate crop maps into an interactive, searchable map, “so people will be able to look at the community gardens near them, and see, for example, if they have a public composting site, or picnic tables, or a herb garden, or whatever they want to know.” Later this year, she hopes to find volunteers who can help her enter old data from Green Thumb’s filing cabinets, to create a map of New York City’s community gardens over time.

Perhaps most importantly, community members will be able to use these concrete numbers to defend existing gardens and advocate more effectively for new ones. Although many New York City gardeners have felt bulletproof ever since they defeated Giuliani’s attempt to sell their land off to developers in the 1990s, Gittleman pointed out that “the legislation that’s been protecting them for a decade expires this September.” In fact, City Council has just issued a draft of the replacement legislation (doc), and although the document praises the “vital environmental and health benefits” afforded by community gardens, it also sets out a clear “Garden Review Process” through which the city can offer existing gardens an alternate site and attempt to develop on their land.

Clearly, Gittleman’s project could not come at a better time. While she is the first to admit that community gardens are not a perfect solution (over time, understandably, they tend to become less community oriented, and more “owned” by the people who cultivate them), they are still an incredibly important amenity for a city that has set ambitious goals to reduce trucking, improve air quality, and increase fruit and vegetable consumption by 2030.

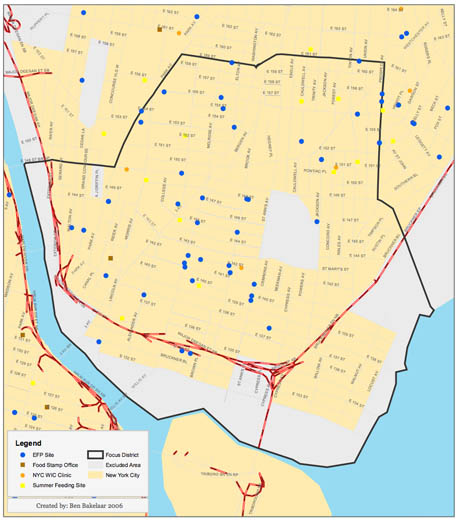

IMAGE: Map showing government and charitable food provision in the South Bronx (including Emergency Food Provision sites, Food Stamp Offices, NYC WIC Clinics, and Summer Feeding Sites). Map created by Ben Bakelaar in 2006 for the New York City Coalition Against Hunger’s report, Mapping an End To Hunger (more, larger, and interactive maps available online there). Gittleman explained that for her thesis at Tufts, she “mapped Boston’s community gardens, food retail of all different sizes, and also socio-economic and demographic data from the census, and then used that to do a statistical analysis of where community gardens and food retailers were in terms of vulnerability to food insecurity.” Eventually, she’s hoping to do something similar in NYC.

I’m on board as a volunteer already, and you can be, too—Gittleman told me that she is still actively seeking sponsorship, interns, and volunteers. Depending on your time and your talents, she has just the job for you, and in return, she promises pizza, beer, and the opportunity to visit the varied community gardens of New York—not to mention your chance to find out exactly how many radishes this city can produce.