I am somewhat astonished to find that I haven’t written about the New York Public Library’s amazing menu collection on Edible Geography before.

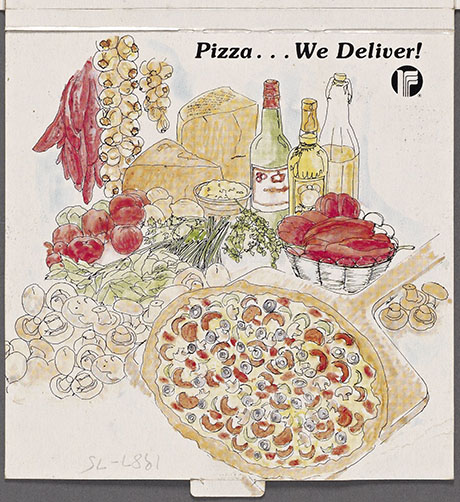

IMAGE: A pizza delivery menu from Radisson Hotels, 1987. NYPL Menu Collection.

NYPL Culinary Collections Librarian Rebecca Federman spoke about it during Foodprint NYC, describing the ways in which researchers have used the archive to trace the drop-off in New York harbour oyster numbers through the bivalve’s gradual disappearance from all but the fanciest of menus, the boom in French restaurants in New York City following the 1939 World’s Fair, and the supersizing of the American menu:

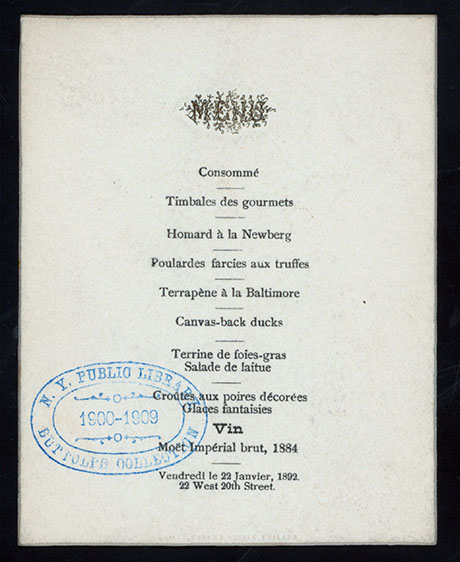

One pattern I’ve noticed is that the early menus are tiny. As we get into the 50s, 60s, and 70s, we have to find these huge boxes to fit the IHOP menu, which is an enormous globe. We have a really simple menu that was from the Bradley Martin Ball […] — it was this enormous ball in 1892 in Manhattan that was completely over the top, but the menu is just a simple little tiny menu.

IMAGE: Menu from the Mrs. Bradley Martin ball, 1892. NYPL Menu Collection.

The collection began thanks to the efforts of a library volunteer, Mrs. Frank Buttolph, who was described by former New York Times restaurant critic Bill Grimes at Foodprint NYC as “an enigma wrapped in a riddle or whatever Churchill said about Russia.” Federman agreed:

In terms of who she was, you’re right — there’s very little information about her. She collected menus and she collected postcards with lighthouses on them and she did some translations, so she was obviously fairly learned, but other than that… […] We have this amazing collection and the bulk of it is really from 1900 to 1923, and those are the years that she was at the library.

There’s a pretty steep drop off from the 20s to today. So, if anyone has menu collections, I take everything!

As soon as I heard this, it became my secret ambition to contribute to the collection myself. My donations may never reach Buttolphian proportions, but in 2010, I asked whether Federman would be interested in a menu from the special Quarantine dinner created by a razor, a shiny knife as part of the Landscapes of Quarantine exhibition that Geoff Manaugh and I co-curated at Storefront for Art & Architecture, and she graciously accepted.

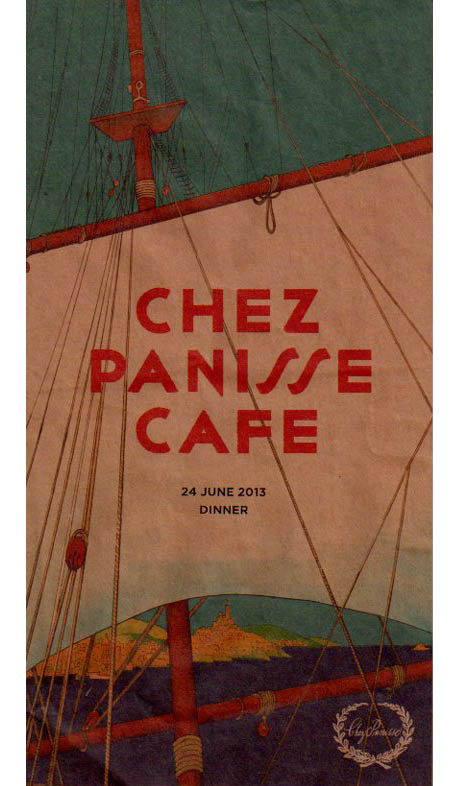

Today, I put my second contribution in the mail: a menu from Alice Waters’ iconic Chez Panisse cafe, from the first night it re-opened after the fire.

I was lucky enough to eat dinner there that night as part of the inaugural UC Berkeley-11th Hour Food & Farming Fellowship cohort. Fellow Fellow Bridget Huber grabbed a menu at the end as a souvenir, which reminded me to take mine home too, in the hope that it might be worthy of accession into the New York Public Library collection.

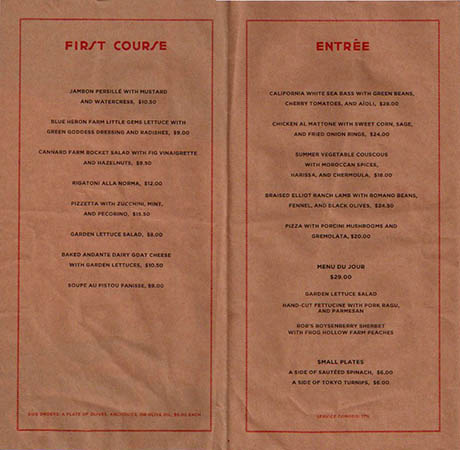

IMAGE: For the record, I had the Little Gems, followed by the sea bass, which was quite plain and tasted utterly incredible.

IMAGE: I was led astray by the wild strawberries that came with the pannacotta, and ordered that despite not really liking pannacotta. I should have had the galette, but I was too full to think straight.

As someone with serious archive fever — I can lose hours and find endless inspiration browsing the ephemeral detritus of daily life, from a collection of state gifts to the German Democratic Republic (one of my more bizarre former jobs) to the complete run of Display World, the trade journal of department store window design (discovered during a Venue visit to the Prelinger Library) — I feel inordinately proud to be contributing, in some small way, to the procrastinatory diversions and/or valuable research of future generations.

As it turns out, it’s possible to combine my two impulses, and contribute to the collection while exploring it, by helping with the NYPL’s menu digitization effort. Thus far, volunteers from all over the world have transcribed and geotagged 1,256,995 dishes from 16,895 menus, in order to make the archive searchable by food type (e.g. sundried tomatoes) and preparation name (à la king, for example), as well as by restaurant location.

There are many more menus to go (right now, a set of 1912 menus from the Waldorf Astoria is awaiting transcription), and getting started is remarkably easy. There’s even an open API for any aspiring app creators — imagine being able to browse historic menus from whatever restaurant you happen to be sitting in, as well as its predecessors at the same address, to see how the way we dine in public has shifted over time.