William L. Fox (Bill) is a writer and the Director of the Center for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art. His ongoing interest, whether writing about Antarctica, the Great Basin, or Los Angeles, is in the ways in which people make sense of landscape. To that end, he has accompanied NASA astronauts to Devon Island, where they practice Martian exploration, driven for miles on the dirt roads of the Nevada desert with earthworks sculptor Michael Heizer, and hung out with Hollywood special effects expert Bob Hurrie as he builds and then blows up a model French village.

IMAGE: A half-dozen examples of Fox’s prolific and excellent output: Aeriality: On the World from Above, Terra Antarctica: Looking Into the Emptiest Continent, Making Time: Essays on the Nature of Los Angeles, The Void, the Grid & the Sign: Traversing the Great Basin, Mapping the Empty: Eight Artists and Nevada, and Driving to Mars.

He has also, I discovered recently, spent some time moonlighting as a wine label writer.

Food writing and its various subgenres, from Japanese sushi manga to beer bottle fiction, are a source of endless fascination to me, shedding equal light on the way we think about both food and language. In the world of wine, descriptors are particularly loaded, as the vagaries of sensory perception meet the marketing language of value attribution.

In an understandable reaction to the flowery bouquet of anise, graphite, and persimmon often conjured up on the same label, a recent New York Times article by Eric Asimov suggested that wine descriptions should be limited to two words, sweet and savoury. Meanwhile, just last week, Slate ran a fantastic article by Coco Krumme that correlated words and cost, finding, for example, that expensive wines are described using singular flavour analogies such as “tobacco” or “chocolate,” whereas a cheap wine tends to get abstract terms such as “fruity” or “clean.” “Armed with this information,” Krumme writes:

We could, for example, create the most expensive-sounding review in the world: A velvety chocolate texture and enticingly layered, yet creamy, nose, this wine abounds with focused cassis and a silky ruby finish. Lush, elegant, and nuanced. Pair with pork and shellfish.

And then there is terroir. In their Food for Thinkers post, Smudge Studio quoted geologist Terry Wright saying that “A label without reference to soils types and roles is leaving one half of the story of the wine in the dust.” The idea that place affects the taste of food, so that in turn, wine or chocolate or coffee made from berries or beans from a unique geographical location can be interpreted as an expression of the land is, of course, an endless source of interest for a site called Edible Geography.

So you can imagine my delight when Bill, BLDGBLOG, and I had the chance to sit down and talk about all of these things recently. Our conversation is below, and in it, Bill describes his education as a wine label writer, the history of the blurb, the influence of minimalist poetry on the language of advertising, and much more.

•••

Edible Geography: How and why did you get into writing wine labels?

William L. Fox: Here’s the story: I’m in Portland, Oregon, and I’m working as an independent writer. I’m writing catalog essays for people, I’m working on books, and I’m going to the Antarctic. And I’m completely broke.

Then Robert Beckmann, a painter from Nevada, calls me. His high school buddy from Pennsylvania has moved to Oregon and started a winery. This guy, Dave Grooters, is an ex-software engineer — really smart and a wonderful guy. Winemaking is his new life, so he’s moved to Oregon.

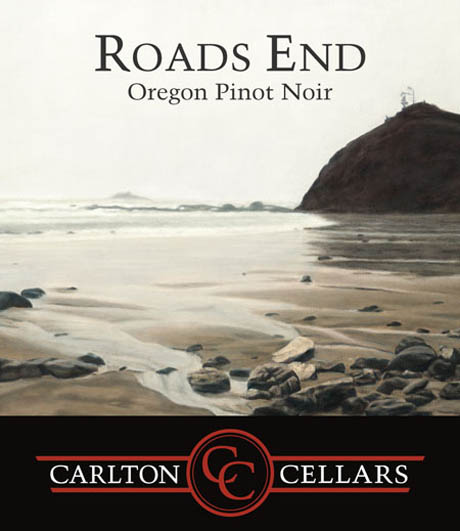

So Dave Grooters hires his buddy Beckmann to paint the wine label for the first release, a high-end Pinot Noir called Roads End. The winemaker is a man named Ken Wright, who’s a god of pinot makers in North America.

IMAGE: Robert Beckmann’s painting on the label of Carlton Cellars’ Pinot Noir.

While they’re talking about the label, Dave says to Beckmann, “God, I wish I knew someone who knew how to write about wine.” Beckmann replies, “Well, you should talk to Bill Fox. He’s never written about wine, but he’s a writer. And he’s in Portland.”

Dave Grooters calls me, and I immediately call my friend David Abel, who’s a professional book editor and an all-around genius, and tell him, “David, I’ve got to drag you into this because I’m not going to do this by myself. We’ve got to do this together.” So the two of us go and meet with Dave Grooters and his wife Robin.

David and I are sitting in Dave and Robin’s living room, at their coffee table, across which is spread a phenomenal array of some of the world’s great pinots. Dave says to us, “I want you to taste these pinots. We’re going to walk through these so you understand the terroir from which each of these wines comes.”

From the start, there was nothing about blackberries and chocolate and all that nonsense. It was all about where the berries are grown, how the vines are treated, how the berries are picked, and so on. It was really about terroir: land, place, and our connection to it. Dave explained that the first release was going to be called Roads End, because that’s a particular beach he and Robin went to that for them represented Oregon and the aspiration they had for the wine.

In that first conversation, it was clear that we had to write about place and climate, and that our label would have nothing to do with all of these California affectations about how we describe taste in terms of other foods. We weren’t going to go there. We weren’t going to become this analogue wine. We wanted to be true to where the wine is produced and where the berries are grown.

That’s how I learned how to describe wine: writing the back labels of wine for Carlton Cellars. They have their own vineyard now, and it’s an exquisite site. It reminds me of Wallace Stevens’s “jar upon a hill” around which the landscape is ordered — there is a tree around which this vineyard is ordered.

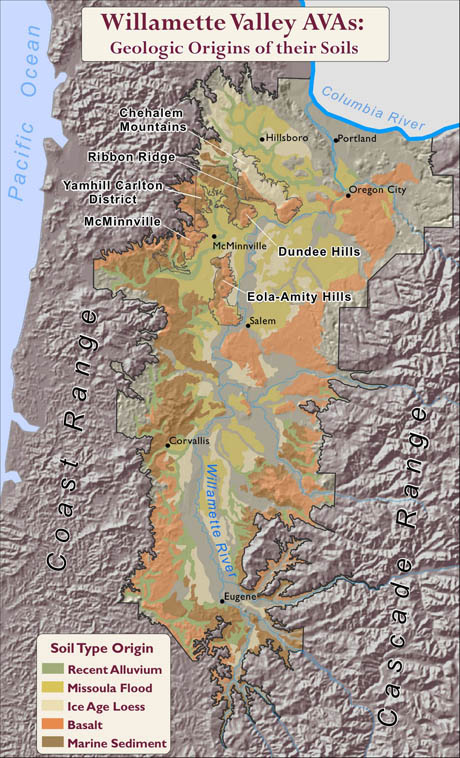

Their wines show a sensitivity, in both the wine-making and, hopefully, also the writing, to the soil and the climate. We thought about it in terms of the clay to sand to volcanic mixtures and how that affects what the berries express, what direction the wind comes from, and the temperatures at certain times of the year — in particular, how close can you get to freezing to intensify the sugars at that crucial moment when the fruit is coming to a state of ripeness.

BLDGBLOG: So when it comes to describing the wine, it’s almost like you’re treating each wine like a Weather Channel report on the exact climate that exists on a certain hilltop during a certain month?

Fox: You could combine a Weather Channel report with a USGS geologist’s field report with a geomorphologist’s soil analysis, and you still wouldn’t quite have it.

So many vineyards are archaeological sites, for example — maybe they are post-agricultural of some other output, or maybe Native Americans burned the site as part of their landscape management. There are people who pretend that if apricots, for example, were once grown on a plot of land, they can still taste them in the wine. I think that’s possibly the silliest thing I’ve ever heard — but it is true that you can tell the difference between major soil regimes and how the soil has been treated.

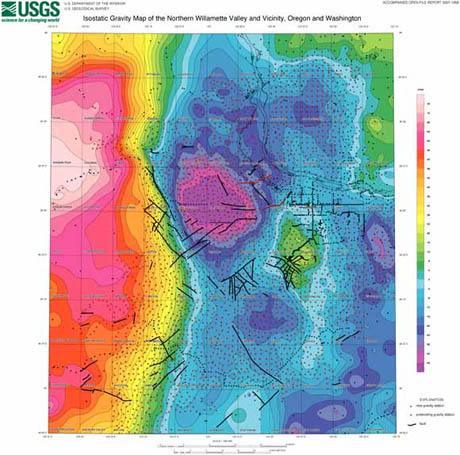

IMAGE: Soil map of the Willamette Valley, via.

Edible Geography: Did you taste the soil?

Fox: No. I walked the land, but I don’t eat dirt. [laughs] That said, I have spent a fair amount of time with geologists in the field, and they love to taste rocks. It’s one way that they can tell how the world has acted upon materials. They can also tell a little bit about the composition by taste.

It’s like when I’m working with NASA on Devon Island and everyone is in pressure suits, wandering around trying to figure out how we would do geology on Mars. There are several complaints that geologists have about working in a pressure suit. The vision — and that’s where eighty percent of your information comes from every day — is actually not so bad in a suit, because the bubble’s pretty big. One problem is that you can’t touch anything — you can’t actually feel anything on your skin, because you have gloves in the way. That makes it hard to tell the texture of rocks, which would tell you how hydrology has acted on it. What’s worse for the geologists, though, is that you can’t taste the bloody thing. On Devon Island, for example, if you put rocks in your mouth, you’ll often taste hydrocarbons. When you’re in a suit, you can’t do that.

I will occasionally taste coarse materials — with small rocks in the Southwest, for example, I can sometimes use taste to figure out what’s going on in terms of stream action. But I wouldn’t have a clue where to start in terms of tasting dirt in the Willamette Valley. People who really know their wines don’t even have to taste the soil. They can walk onto a piece of property and smell it. Of course, wine growers always hire a scientist to come in and do the soil analyses, because you don’t spend a lot of money planting a vineyard without knowing everything about the soil and the drainage and so on.

IMAGE: The K1 robot exploring Battle Herc Ridge, near the Haughton Mars Project research station on Devon Island, in August 2010. Photo by Dr Trey Smith (NASA Ames), NASA/Mars Institute/Haughton-Mars Project.

Edible Geography: What effect do inputs — organic fertiliser versus non-organic, or pesticide sprays — have on the flavor?

Fox: Most people that I know who make high-end wines put as few chemicals as possible in the soil because it distorts everything. On the other hand, you can’t afford to be wiped out, you know? It’s a balance.

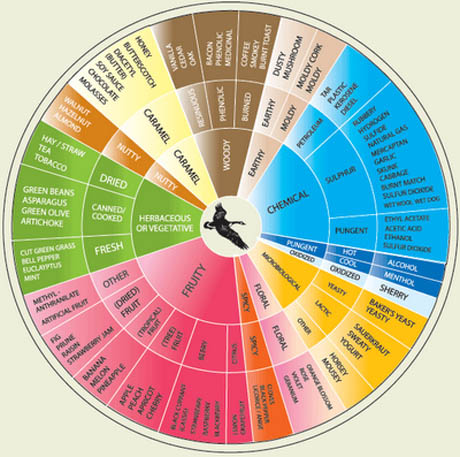

Edible Geography: I’ve come across something called the UC Davis Wine Aroma Wheel for describing wine. Is that something you drew on, or not at all?

Fox: UC Davis does great work and they’re amazing research scientists, but the school has a very particular and highly financialised relationship to the California wine industry. I’m talking about Oregon wines. Utterly different.

Edible Geography: And descriptors are one of the ways you would set them apart, as well?

Fox: Yes, absolutely. California wines are defined by flavour analogy; Oregon wines are framed in terms of the land.

IMAGE: UC Davis Wine Aroma Wheel by Ann Noble

Edible Geography: How long did you write wine labels for?

Fox: I only did it for a short time — about a year. It was one of the most intimate and inclusive and intelligent introductions I’ve ever had to a landscape. There was the geology and meteorology, but also the wine culture of the Willamette Valley — the entire terrain, not just the terroir, and how that translates into territory.

As a result, I’ve come to appreciate wines that are produced out of grapes grown upon hills, rather than in valleys. Duckhorn Cabernet, which is grown on Howell Mountain in Napa, is a great example. A Howell Mountain Cab isn’t that typically sweet California Cab where it’s almost got too much sunshine—it’s almost too benign a climate. Howell is just big enough of a mountain that the vines get stressed a bit more, and that gives the wine more complexity.

IMAGE: A USGS isostatic gravity map (measuring rock density) of the Willamette Valley.

Edible Geography: So you can taste the difference between grapes from a hill and grapes from a valley?

Fox: Absolutely. You can tell that the micro-climate is different. It can get very confusing, because there are ways of making the wine that will structure it differently, so you can change one thing into another. But in general, if it’s a pretty honest wine — in other words, if you’re not trying to change the character of the wine through the way in which you make it, but instead you’re trying to express the terroir — you sure can tell the difference. The valley has a less vivid taste in your mouth. It’s not going to have the highs and lows — the depth — that a wine produced from grapes on a hill has the potential to produce.

But it is entirely possible to fool people, to a certain extent. There are so many things that you can do in a vat that will change the nature of how things are tasted — where the wine comes alive on the tongue, for example, whether it be in the front or in the back, or almost in the throat, it’s so deep. I’m nowhere near clever enough to straighten out all that stuff.

But in a true blind tasting, what you taste and what you appreciate is founded on things that are so much more fey than that.

Edible Geography: Your personal infrastructure of analogies takes over.

Fox: Exactly. For true blind testing, you have to do a really large sampling of both people who know about wine and people who don’t. I find most blind testing competitions sort of silly, because they’re so unscientific. It’s just an extremely selective group of people with predetermined tastes and ways that they understand wine.

Look, what you ate the night before affects how you taste the wine the next day. What time of the month it is, if you’re a woman, will affect how you taste wine. How hungry you are, what perfume you’re wearing or laundry detergent you used — basically, everything else that is going on in your olfactory system will affect it.

If I bring a bottle of Roads End down to Reno, I have to let it sit for at least three months before the molecular structure settles down enough for it to taste like what it tasted like in Portland. A wine gets shaken up a bit just by driving down a road from Portland to Reno, and it’s not quite the same wine until it’s had the chance to settle down. So that’s a variable affecting taste: from how far away did the wines come, and how long did they sit before you tasted them?

There are some objective standards. You can really tell whether a wine has one, two, or three dimensions, to use a whiskey metaphor. You can tell when a wine is large and has rooms to walk into versus something that’s more like a closet — you taste it and it’s done.

You can also taste the amount of money that was spent to buy the care to make the wine. Actually, if you wanted to say what’s more apparent in taste than anything else, it’s probably money. You can taste the level of care that was taken in making the wine, and care costs money.

In a way, oddly enough, the terroir becomes financial, not necessarily geographical or geological. Of course, in reality, it’s always a mixture. The money will just enhance and take the best advantage of each terroir. But, if you’re willing to only take the very best berries as they’re moving along the belt, and only berries from vineyards that this year had a really good week at the end of a particular month, so they have a specific profile in terms of tannins and sugars, and so on — you can taste that level of care.

That said, you can be the most scientific and experienced vintner in the world and still blow it. Some guy next door who’s a tyro can make a better wine than you that year, just because of how things come together.

Edible Geography: How did your experience affect the way you read wine labels? Is there an element of competition for you, still?

Fox: I do still go to the store and read the back labels. I chortle sometimes, and other times I’m in awe. I’m the same way with books, as an author. That’s what a wine label is — a small book.

IMAGE: Although he was reluctant to name names, Fox later cited Duckhorn Vineyards as an example of a label he admires, noting that “The wines are so good that they can afford to make puns.”

BLDGBLOG: What are some of the best labels you’ve read? What do you look for in a label?

Fox: I’m not going to name names, but there are some I really admire. Of course, you can tell a lot from the front label. In the store, the really high-end wines are on the top shelf, and the really bottom-end are on the lowest shelf — in that respect, wine is just like toilet paper. The stuff everyone’s going to buy is in the middle, and you try to distinguish yourself in that range if you want to sell a lot of wine. So there are the catchy names and vivid labels, which are designed to appeal primarily to women because they do more of the shopping than men, and they sell better than labels that are dry or stern and forbidding, and don’t give you a lot of information on the front.

Edible Geography: Are there any words that are particularly meaningless on a wine label, the way “natural” on food packaging means nothing at all.

Fox: You’ve hit on a key issue. It’s interesting: olive oil is in a similar state of linguist confusion right now. I’ve spoken with guys in Australia who are making absolutely spectacular olive oils, and they were scratching their heads and cursing at what the Americans and the Europeans have done to the olive oil trade. These Australians are making really incredible olive oil, but they have no nomenclature by which they can explain and defend the virtue of what they do.

What we’ve done in the highest consuming nations, in a peculiar kind of way, is that we’ve valorised a certain kind of vocabulary that is shared in common with high-end wine, chocolate, olive oil, coffee — all things that you don’t have to have but you really want. These foodstuffs have adopted a particular vocabulary to make a hierarchy of value in their industries, and, of course, that is subject to corruption the minute enough consumers believe that A means something better than B.

I think wine started the process. Chocolate and coffee and so on are all are imitating wine. It’s a Pandora’s Box sort of situation — it’s actually quite interesting to watch how the vocabulary filters through into how all of these other luxuries are described. Wine labels are sort of a telling document in this process of how we establish and then co-opt hierarchies of value.

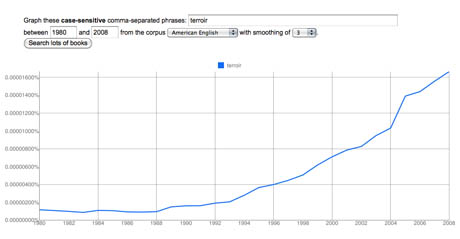

IMAGE: Google N-gram showing the frequency of usage of the word “terroir” in books published between 1980 and 2008 in American English.

Edible Geography: And yet French wine labels, from the most exclusive to your standard table wine, say nothing.

Fox: Exactly. You have to know something about the region, which is to say, either the geology and geomorphology and climate where the wine was produced, or you have to know the reputation of the wine-makers themselves or that a particular village is known for a particular balance. Which is to say, you have to know the terroir. French wine labels don’t even list the grape — it’s all about the terroir. And the terroir is not just a region — it’s a style that’s evolved to take advantage of the conditions in that region.

And Americans are a loquacious people.

BLDGBLOG: I wonder if you can find parallels to that in the different ways novels are packaged in Europe and the US. In France, novels never say anything on the back, whereas I want to know what it’s about before I buy it.

Fox: I think the British can actually take credit for that. There was a period after the Second World War where the British were beginning to mass import continental products — from cheese to literature — and the art of the blurb was invented.

Penguin was publishing French novels, for example, and they were trying to describe the sophisticated cultural pleasures of Europe to a relatively inexperienced population. Of course, England has spectacular novels and fantastic cheese. But in order to commodify products coming from Europe, in order to build up a market where there wasn’t one before, and in order to ratchet up national economies after the war, you get the deployment of the blurb.

Obviously, there had been advertising before World War II — but I’m willing to argue that the blurb came into its own as a literary form in Britain in the Fifties. Of course, no one can own the blurb — it’s a pretty large genre, and Americans have certainly embraced it. It actually works the same way for us — the Brits know more than we do, the French know more than the Brits, and so on.

There’s a whole history of blurbism that allows us to become more sophisticated and experienced as a culture. It’s all about how you sell stuff — you have to educate the consumer.

A back wine label is the ultimate in the blurbing business. If you think Stephen King’s blurbs have to be a paragon of precision, think about how compact the back label of a wine bottle is. You have so few words — eighty would be lengthy.

I started out as a minimalist poet, and that served me well. My friend David Abel is also a trained poet, and he used to run the best avant-garde bookstore in New York City — The Bridge. He edits down to the quantum level. He really can take a screwdriver to anything anybody ever wrote and simply get the fuel mixture very lean. The wine labels on those early Roads End vintages are, I think, quite clean.

BLDGBLOG: Are there anthologies? The 150 Best Wine Labels Ever Written?

Fox: No, but I think it’s a book we should do! I think it’s a great idea.

BLDGBLOG: There’s an anecdote I remember about the minimalist poet Aram Saroyan. He also worked in advertising, and he’s the author of one of those catchphrases that most Americans will know, which is that “Raid kills bugs dead.”

Fox: It’s like James Dickey — he wrote “The pause that refreshes!” for Coca-Cola. Wallace Stevens, to go back to the “jar on the hill” I mentioned earlier, worked in advertising too. That kind of concision in American language: you find it in advertising, minimalist poetry, and the best wine labels.

Edible Geography: Do you know what the wine label writing industry looks like now?

Fox: I have no idea. But I do know that there’s a real self-consciousness among high-end winemakers about not being flowery — not trying to take your wine and hook it to a cake, you know? There’s a real notion of trying to be honest about here’s how and where we make the wine.

But the bottom line is that language is a great deceiver. You’ve just got to taste stuff yourself, whether it’s a cheese or a wine or a restaurant, to know if it’s any good.

BLDGBLOG: What’s the wine label editorial experience like? Did wine-makers come back to you and ask you to use or not use certain words?

Fox: Absolutely. Someone will say, for example, “I just don’t want our geology to be identified with that of the Willamette Valley. I want to make sure we’re distinct from that, because we’re not actually in the valley, and it makes a difference.” To make that distinction, at the level of language, means there are words you just can’t use.

When you look at a vineyard, it’s a really small piece of property. Compared to a wheat field, it’s tiny. Everyone’s trying to parse out the finest level of distinction that they can draw, so that the mind of the consumer has a hook to put their product on. It’s never not a sell. Even the most serious, honest, committed wine-maker is aware of the fact that if he or she cannot sell the wine, then they can’t continue to make wine or keep the land.