IMAGE: Walmart, Mexico City. Walmart sells more food each year than anyone else in Mexico. It is the country’s biggest private employer, with a range of supermarkets (the high-end Superama and discount Bodega), department stores (the wonderfully named Suburbia) and restaurants (VIPS, El Portón, and Ragazzi) to suit all budgets and tastes. Rachel Laudan took me to her local Walmart (a convenient five-minute walk away) and commented on the Walmart-induced improvement in Mexico’s customer service.

Apologies for the prolonged silence here at Edible Geography. It is one of the ironies of Postopolis!—the blogger-curated “Ponzi scheme of ideas” (in the words of its co-founder Joseph Grima) whose most recent iteration took place last week in Mexico City—that there is not really enough time to post during the event itself.

Now—post-Postopolis!—I’m excited to begin belatedly reporting on a frenzied and fascinating week of presentations, excursions, and garañona. One of the highlights of my time in DF was the chance to meet Rachel Laudan, whose blog is on my regular reading list.

IMAGE: Rachel Laudan holding Mexico’s favourite snack, the Twinkie-esque Gansito.

Rachel Laudan’s background is as a historian of science but, while teaching at the University of Hawaii, she became interested in the history, geography, and politics of food. Her subsequent book on the fusion cuisine of Hawaii, The Food of Paradise, won the prestigious Julia Child Award in 1997. Although she is originally from the UK, she has been living in Mexico for the past twenty-odd years—and luckily for me, she moved to Mexico City itself in February.

Despite being busy with the final draft of her forthcoming book (“a world history of food”) for the University of California Press, Rachel took me on a lovely guided wander round the varied foodscape of her neighbourhood. Beginning at Walmart and ending with a filling and economical meal at a comida corrida, via a traditional bakery, we explored the intersection of food, class, and economics in contemporary Mexico.

From the broccoli in our lunchtime tortitas (originally grown for export to America, it is now replacing the more traditional cauliflower) to the upper-class custom of a pre-marital stint in culinary school with one’s servant, Rachel traced the edible archaeology behind almost everything we saw.

IMAGE: Wedding cake model at a Mexican bakery; traditionally, upper-class girls would be sent to culinary school with their servants before they got married, so that they could learn how to supervise (and the servants could learn how to make fancier European dishes).

Our mini-tour was then capped by Rachel’s presentation at Postopolis! DF, where she spoke to an eager audience of designers, architects, urbanists, and bloggers. I’m delighted to be able to publish the transcript of Rachel’s provocative explanation of the direct link between advances in grain processing technology and the emergence of a thriving middle class in Mexico City, below.

In due course, Domus, one of the event’s co-sponsors, will be releasing the edited video of her presentation (and all fifty others) online, so that you can fully appreciate Rachel’s maize-grinding demonstration!

•••

Rachel Laudan: All cities require fuel: oil, gas, electricity, and so on. What I want to talk about today is the energy that fuels the people in the cities—food. Without food energy, a city is nothing. A city is nothing without the people who work and play and enjoy or suffer through the city, and they require food.

IMAGE: Tortillas. Photo by Nick Gilman, author of a handy guide to Mexico City’s food, via Rachel Laudan.

I want to talk in four short bursts. The first is about what all cities need in the way of food. The second is the reason why Mexico City had a particularly hard time with food. The third describes a revolution in the food of Mexico City that has taken place in the twenty years since I first saw it. And the fourth is about the kind of trade-offs that had to be made to undergo that revolution in food.

So: what do cities need in terms of food? There’s only one way to feed a city, at least historically, and that’s to feed it with grains—rice, wheat, maize, barley, sorghum, etc.. You can go round the world, and there just aren’t cities that aren’t fed on grains, except for possibly in the high Andes. Basically, to maintain a city, you’ve got to get grains into it. Be it Bangkok, be it Guangzhou, be it London, or be it Rome—throughout history, grains and cities are two sides of the coin.

And what do you need in terms of grains? For most of history—really, until about 150 years ago—most people in most cities, except for the very wealthy, lived almost exclusively on grains. They got about ninety percent of their calories from grains.

That meant that for every single person in a city you had to have 2 lbs of grains a day, turned into something that people could eat.

IMAGE: Rachel Laudan holds up a kilo of tortillas—the daily grain requirement for each city dweller.

[Holding up a standard supermarket package of tortillas.] This is a kilo of tortillas. That’s what one person in a city needed. It’s the same weight, more or less, whatever the grain is—you can go to the historical record, you can research in China, in India, in the Near East, and you will still be talking about 2 lbs of grain-based food for every person in the city every day.

So you can do some calculations. If you’ve got a city of a million, like ancient Rome, you’ve got to get two million pounds of grain into the city every day. It’s the same for all the cities in the world— it’s 2 lbs of grain per person. That’s the power, that’s the energy that drives cities.

So let’s start with that for Mexico City. What are Mexico City’s grains? Pre-conquest, of course, it was just maize. Post-conquest, it’s maize and wheat. I want to talk primarily about maize, and we’ll move onto wheat later on.

Maize is not the greatest grain for the person who is preparing it. Because when I say that cities live off grain, I’m actually telling a lie. Cities don’t live off grain. Grain is not edible. Maize is not edible, wheat is not edible—if you eat a lot of wheat or a lot of maize, it will go straight through the system. Grains—maize, wheat, or rice, it doesn’t matter which—are only edible once they have been processed and cooked into boiled rice, bread, tortillas—whatever the end product is. That’s what you eat.

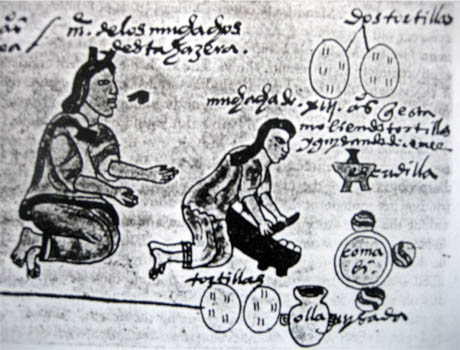

IMAGE: Women grinding maize: a processing technique that remained the same from antiquity until surprisingly recently. Image courtesy Rachel Laudan.

Yesterday, Nicola was saying that food blogs can be a bit girly. Let me tell you, there’s nothing girly about processing maize to make tortillas.

The Mexicans in the audience will know this, but if you don’t, here is what you have to do to turn maize into a tortilla. First of all you have to cook the maize with something alkaline. Today you can use cement, but in the past they used the salt from the dry lake bed around Mexico City. You have to take the grains off the maize, which is very time-consuming, and then you heat it, you cook it, and you rub the husks off.

Then, when you have got your wet-cooked maize, you have to grind it. For thousands of years, Mexican women ground maize like this. [kneels to demonstrate] I’ve spent some time grinding. You have a metate, and you start with your handful of maize and you put it here and you grind it down to end of the grindstone, and it’s not fine yet. You use your fingers to move it back up again, and you grind it all the way back down again. Then you move it back up again—and to get it fine enough to make tortillas you have to do this five times for each handful of maize.

IMAGE: Rachel Laudan mimes wet-grinding maize at Postopolis! DF.

Depending on how good you are, it takes somewhere between fifty minutes and an hour to do enough maize for tortillas for one person. That means for a family of five someone is going to be spending four or five hours a day doing nothing but grind. [gets up] It’s very exhausting, grinding.

When I first got to Mexico, young women, particularly in the country, would say to each other, “Do you grind?” Imagine it! The girl who worked for me when I first came here, when she was twelve years old, her parents handed her the mano, the thing you grind with, and they said, “OK, girl, now it’s time you start grinding.” That meant, in sickness and in health, from Monday to Saturday—on Sunday, you ate stale tortillas—she ground for four or five hours a day.

When I was twelve years old, I had my first period. I though, “Oh my god, is this what I’m going to have to put up with for the rest of my life? Roll on menopause!” But imagine if I’d been a little Mexican girl, twelve years old, and I’d not only had my first period, but I’d also been handed the grindstone and I knew that from then on, for five hours a day, six days a week, I was going to grind…

It is a very, very time-consuming thing. It’s terrible for the individual: arthritis, bad knees, no time to spend with the children, and no opportunity to go to school. It’s also, obviously, not a great thing for the society if you’ve got one fifth of your adults doing nothing but grinding.

IMAGE: Masa on a traditional metate, photo via.

That kind of labour-intensive grinding was what they did in Ur, and in ancient cities of the Middle East and Egypt. By the time you get to Rome, roughly—by about the birth of Christ—in the Middle East and in Europe, they get a rotary grindstone, and instead of requiring one person per every five to spend all day grinding this two pounds of grain that everybody in the city needs, they get it down to one in thirty. Then they get watermills and it goes down to one in three hundred—and nowadays we don’t even think about it! There are big steel rollers up there in Minneapolis and they’re grinding grain for hundreds of thousands of people, using just a handful of workers.

Now why didn’t Mexico do that? Was it just backward? Why didn’t it move to other forms of grinding? The trouble is if you grind wet, you cannot use these other rotary grindstones. So even if the Mexicans had had them, they couldn’t have used them. When the Spaniards came here they brought rotary grindstones, but you just can’t grind wet maize with rotary grindstones. And if you want tortillas—which we now know have nutritional advantages, but they are also a flexible bread, and hence more appealing than the kind of porridge-y things or tamales that you would have otherwise—you have to grind wet.

IMAGE: Atole, a kind of sweetened corn porridge drink, which to me tastes like thin, lumpy rice-pudding. Photo via.

Therefore, in Mexico, right up until about twenty years ago, large numbers of Mexican women were spending five hours a day grinding. Just imagine Mexico City: every household had somebody grinding tortillas. The landscape of Mexico City up until fifty years ago, and in many ways even later, is one of bakeries that make wheat breads for the upper class or perhaps for breakfast or the evening meal, and then in every household, somewhere in a back room, somebody grinding maize to make tortillas for the main meal of the day.

IMAGE: Mexican pastries at Walmart’s in-store bakery.

That’s all changed. You can still find the odd person who grinds in Mexico City, but it doesn’t happen very much.

So, what’s the revolution that’s occurred? What’s happened to Mexico?

It took about a century. In the late nineteenth century, people began trying to find ways of mechanizing this business of grinding and cooking tortillas. Three things happened: first of all, they worked out how to make a mechanical mill that could grind wet. You still find these mills in many rural villages today—people cook their maize at home, and then they take it to the mill and grind it, and then they take it home and cook their tortillas. Those mills really came to Mexico City in the fifties and sixties—it had been invented earlier, but it needs electricity, and the early ones weren’t very good, and so on.

The second thing is that they invented a tortilla machine. If you live in Mexico, or even if you are a visitor here, and you go into any of the big grocery stores, you can see a tortilla machine back in the corner. It’s a kind of Heath-Robinson-esque contraption that cooks the tortillas.

IMAGE: Walmart’s in-store tortilleria

And the third thing that happened, finally—this really took place in the seventies and eighties—is that the company now called Gruma (Grupa Maseca) discovered a way to take the wet, alkali-treated maize, grind it, dehydrate it, and put it into packets. You’ve seen those packets in the grocery stores, I’m sure.

IMAGE: Maseca, photo courtesy Rachel Laudan.

By the 1970s, five percent of the maize for tortillas in Mexico came from Maseca. By the 1990s, it was fifteen percent. Maseca now has plans—whether they’ll pull it off, I don’t know—to take over all the tortillerias in the country.

Another thing that happened, during this crucial fifty-year period between 1945-ish and the end of the twentieth century, was that bread changed in Mexico. Traditional bread in Mexico was bread by the small piece, made in the traditional oven: the bolillo, the semita, and the numerous small breads you still see in Mexican bakeries today.

IMAGE: A bolillo and a semita, photos courtesy Rachel Laudan.

Beginning in 1945, an immigrant from Catalonia, Lorenzo Servitje, bought two second-hand loaf-making machines from the United States—the kind that make sliced white bread. The Servitje family founded the Bimbo company, which is now, as you know, omnipresent in Mexico. Bimbo bread lasts a long time and became widely available, and Bimbo now the largest bakery in the world. It is the fifth biggest food company in the world.

And so now, what does the landscape of Mexico City look like in terms of grains? It’s a whole series of Walmarts with in-house tortillerias and bakeries and shelf after shelf of Bimbo.

IMAGE: Bimbo bread, photo courtesy Rachel Laudan.

Of course, there are trade-offs. Bimbo is not as good as a bolillo. A machine-made tortilla is not anything like a homemade tortilla – it’s not even in the same universe.

Mexican women that I have talked to are very explicit about this trade-off. They know it doesn’t taste as good; they don’t care. Because if they want to have time, if they want to work, if they want to send their kids to school, then taste is less important than having that bit of extra money, and moving into the middle class. They have very self-consciously made this decision. In the last ten years, the number of women working in Mexico has gone up from about thirty-three percent to nearly fifty percent. One reason for that—it’s not the only reason, but it is a very important reason—is that we’ve had a revolution in the processing of maize for tortillas.

Audience Member: What do you personally think about Gruma trying to take over the tortilla business?

Rachel Laudan: I think I’ve got the same mixed feelings that many Mexicans do. It would be nice if there were more masa harina companies, and it would be nice if Gruma couldn’t get a monopoly, but are we going to go back to grinding at home for five hours a day? No.

IMAGE: Walmart’s in-store tortilleria, photo courtesy Rachel Laudan.

Am I terribly upset that there seems to be a near one hundred percent takeover of not-such-good tortillas? Well, one of the interesting things about this story is that we’re apt to assume trends go on forever—but think about two of the things I just mentioned in my talk. There wasn’t a Bimbo company in 1945 and there wasn’t a Walmart in 1945. So I think all kinds of things can and might happen.

One of the negative effects of having had tortillas subsidized for so long in Mexico—which has really aided the poor—is that nobody has wanted to invest huge amounts of money into developing better tortilla machines and flour mills and things. Now, maybe, we’re at a point where we’re developing a boutique market for good tortillas. And there are better tortilla machines coming out now—we’ve got ones that rotate and flip the tortillas like you do on the comal, so they’re much closer to the taste of the handmade ones. So I think there will be a movement for good tortillas.

IMAGE: A Bimbo employee stocking the shelves at Walmart. Rachel pointed out his suit and tie, and explained that the Bimbo company was founded along Fordist “welfare capitalist” principles, paying above the average and demanding, in return, hard work, loyalty and adherence to a conservative social code.

Edible Geography: Did the move away from grinding at home have spatial repercussions? Was there an empty room in people’s houses all of a sudden?

Rachel Laudan: In the city, I’m not so sure. In the country, there used to be two kitchens—the regular kitchen and the black kitchen. In fact, there still often are. The black kitchen is where you grind and where you cook tortillas and the regular kitchen is where you might have your other stove. But I’m sure people can find something to do with that extra space in the house, especially in the city. Now, of course, you’d probably put a great big refrigerator on the floor space that used to be occupied with your grindstone, because with a refrigerator, you don’t have to make your tortillas every day, because they last from one day to the next.

Audience Member: Can you talk about other gender divisions in the production of food?

Rachel Laudan: It’s a good question—I’d like to think more about it. Agriculture was always male, and bakeries were always male. I think a lot of street food is female.

Edible Geography: Just to range further a little further afield, into the global geography of culinary techniques, I’d love to hear more of your thoughts about something you blogged about recently: the Columbian exchange that did or did not happen in 1492.

Rachel Laudan: Well, we’ve all heard about the Columbian exchange. It’s a cliché at this point: Mexico’s gifts to the world and so on. In fact, there may have been an exchange of plants, but there was no exchange of cuisines.

What happened was that European techniques—wheat mills and bread-baking, for example—came to Mexico, but what Mexicans knew about how to process food did not go to the Old World. The process of adding alkali to maize and grinding it wet didn’t go. The Europeans ground maize like they ground wheat, and they got pellagra, and they went blind, and they died.

The technique of dehydrating chiles and grinding them and rehydrating them to make some of the healthiest sauces in the world has never moved out of Mexico. It hasn’t even got to the United States, for goodness’ sake—what most of the United States thinks is a salsa is some chopped-up tomato with a few chiles in it. I mean, that’s a sort-of salsa, but it’s nothing like the wonderful salsas you find in Mexican cuisine. So no, there wasn’t a Columbian exchange in food. But the question of why not needs a much longer answer than we have time for today.

[NOTE: A huge thanks to Rachel Laudan for agreeing to speak at Postopolis! DF, preparing and delivering such a fascinating talk, and allowing me to publish it online here—not to mention generously showing me round her corner of the metropolis earlier the same day. To find out why there was no Columbian exchange, as well as much more, you will want to read Rachel’s blog at www.rachellaudan.com and follow her on Twitter @rachellaudan.

More recaps and round-ups from my week in Mexico City are forthcoming; meanwhile, many thanks to the organizers, sponsors, and fellow bloggers who made Postopolis! DF such a fantastic, overwhelming, and fun event.]