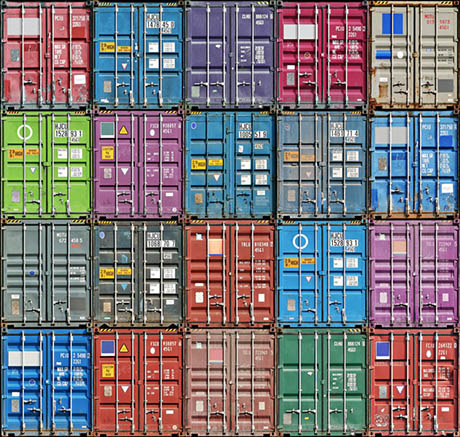

IMAGE: Shipping containers, via.

Intermodal containers — the standardised steel boxes that carry 90 percent of everything* — are ubiquitous: stacked five or six high on enormous ships, tracing their way across the landscape in long ribbons on railways or split up into individual units and hauled by lorries on motorways, before being built into Lego-brick-style fortresses at major ports.

But their ownership, contents, and routes are a mystery to most — the same orange box could hold rubber ducks, spearmint flavouring, and/or tins of cat food, it could be the property of an 86-year-old Taiwanese billionaire or a 165-year-old German company majority-owned by the City of Hamburg, and it could be on its way to Yokohama, the Gulf of Aden, or a logistics hub in suburban Philadelphia. And, although its exterior marking and colouring will provide some clues as to the box’s identity, the ability to decode that information is rather rare.

IMAGE: The Container Guide.

Enter The Container Guide, a new book designed to answer the prayers of any aspiring container-spotters. In the words of its authors, Tim Hwang and Craig Cannon:

The Container Guide, drawing inspiration from classic Audubon birding guides, is a practical field guide to identifying containers and the corporations that own them. Inside you’ll find virtually every major shipping concern brought to life in full-color on durable, tear- and water-resistant paper. The included photographs, logos, and container colors will help you quickly identify the corporation behind almost any container you spot in the wild. Each company’s corresponding entry provides rich historical background and data on their revenue, trade routes, and habits.

Hwang and Cannon are gathering pre-orders for The Container Guide on Kickstarter right now, and aim to have it on backers’ bookshelves by January 2015.

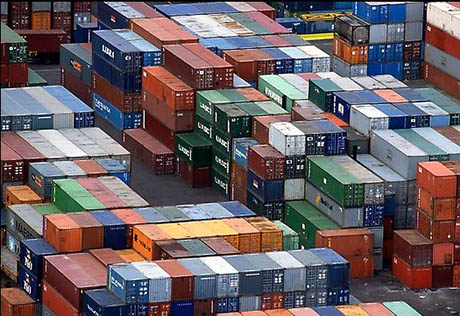

IMAGE: Containers stacked in port, via Gatekeeper USA, a “container security solution.”

Hwang is founder and director of the Bay Area Infrastructure Observatory, “a citizen alliance devoted to exploring and celebrating the large-scale built systems that make modern life possible,” while Cannon is the co-founder of Cultivated Wit and former Graphics Editor at The Onion.

They bring accordingly different motivations to their intermodal investigations: Cannon told me that he is particularly partial to Hanjin containers, “because I worked on a project that involved hand-painting container logos and grew fond of their ‘H’ mark.”

Meanwhile, Hwang is interested in spotting my own personal favourites: reefers (refrigerated containers), the crucial link in the global cold chain that connects growers and consumers around the world.

IMAGE: Reefer plug poles at Maher Terminal, Newark, via Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue’s Geography of Global Transport Systems.

In fact, I will be contributing a short essay to the book, exploring the early days of reefer experimentation. Rose George, author of the recent book Ninety Percent of Everything, is also contributing a primer on the role and history of containers in shipping, and Luke Iseman of Boxouse will add yet another perspective, based on his experience of converting and living in a retired shipping container.

These additions to the classic field guide structure are intended, Cannon explained, “to make it fun to read both at home and in the field.”

IMAGE: Shipping container doors contain identifying information. Photo via.

Curious, I asked Cannon whether there was already a subculture of container-spotters.

“Definitely,” was the response, with spotters dividing into two distinct tribes: those who track container ships, and those who track the containers themselves on port and on land. “Ship trackers,” he explained, “spend time on sites like MarineTraffic, observing shipping patterns and then posting videos of their sightings to YouTube. They’re usually looking for new or rare types of ships.”

Meanwhile, the container spotters focus on “port logistics and their favorite company’s containers”:

Given that containers are all the same size, choosing a favorite is really a matter of personal taste. […] MOL is definitely a popular one — side note: here’s an article about creating the alligator logo. Personally, I like the Hanjin “H” mark and Hapag-Lloyd orange.

Hwang, on the other hand, confesses to being “an enormous fan of the Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL) insignia with the flower design in the ‘O’,” while I am rather fond of the Maersk blue with a white star.

IMAGE: The OOCL “Bangkok” on its maiden voyage, photographed by Daniel Eckhardt.

The book will offer the container-spotting novice a guide to parsing each box’s distinctive exterior plumage: the logo and colour, at first glance, but also the more detailed information hidden behind its unique ISO 6346 number. From that code, Cannon explains, “you can discern the owner, type of container (U = freight containers, J = detachable freight container-related equipment, Z = trailers and chassis, and R = refrigerated containers aka ‘reefers’), and the serial number for tracking.”

There are still many unanswered mysteries that the duo hopes to get to the bottom of in their research. Where are containers born? (Cannon pointed me to this video of a Chinese factory, which we both recommend watching on mute.) Can you tell the age of a container from its exterior? (Discontinued logos such as the MOL alligator provide one clue.) How many containers lie at the bottom of the ocean? Are there container hospitals, or do damaged ones just get scrapped?

IMAGE: The MOL alligater and Maersk star on two model train set reefers.

I asked them to share the most surprising thing they have discovered in their early days as container nerds: for Cannon, it is the fact that Maersk is a real person’s first name, and that “flags of convenience,” in which a Danish ship is registered in, for example, Panama, in order to benefit from its lax regulations and reduced operating costs, are not only legal, but normal practice — roughly fifty percent of the world’s merchant marine fleet is registered in either Panama or the tiny African country of Liberia.

Hwang, on the other hand, has been amazed by “how political the competition between the companies is.”

The making and breaking of cooperative agreements between major shipping concerns — often with pretty dramatic titles like “The Grand Alliance” and “The New World Alliance” — are a big part of the global chess game of container trade.

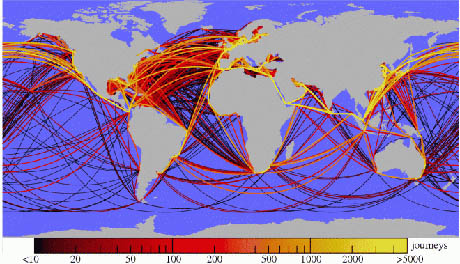

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the project will be the way it illuminates global trade routes: Hwang and Cannon are working with GIS specialist Xiaowei Wang (also of the Bay Area Infrstructural Observatory) to map container migration patterns.

IMAGE: A year of global shipping routes, visualised, 2009. Image by Bernd Blasius from “The complex network of global cargo ship movements,” Pablo Kaluza, Andrea Kölzsch, Michael T. Gastner, and Bernd Blasius, J. Royal Society: Interface, via Wired.

If all this has piqued your interest, you can secure your copy of The Container Guide here. While you wait for it to arrive, you can feed your container curiosity by looking back at the BBC’s Box project, which tracked one container’s movements and contents over the course of a year, taking auto parts from Brazil to Japan, and tape measures from Shanghai to a Pennsylvania outlet of Big Lots. You can also pick up a copy of Mark Levinson’s history of containerisation, The Box, as well as, of course, Rose George’s Ninety Percent of Everything. And, if infrastructural appreciation is your cup of tea, why not sign up for the Bay Area Infrastructural Observatory’s first-ever conference, at the end of May? There are field trips to the Port of Richmond and a construction aggregate quarry, and I’ll be one of the speakers!

* 90 percent of everything that is not bulk or specialised cargo, such as oil (which accounts for a quarter of all goods transported at sea), iron ore, grain, grain, juice concentrate, and cars.