IMAGE: An English cucumber straightener from the mid-nineteenth century, via the Old Garden Tools museum.

This is not what you (probably) think it is. It is, in fact, a glass cucumber straightener from the mid-nineteenth century, invented by George Stephenson, who also happened to build the first public railway line in the world.

Apparently, Stephenson grew frustrated with the crookedness of the cucumbers growing in his Tapton House gardens and had several glass cylinders made at his Newcastle steam engine factory in order to control the wayward vegetables.

IMAGE: George Stephenson’s patented cucumber straightener in front of its home at the Chesterfield Museum, Derbyshire, via Tanners Yard Press.

Rumour has it that Stephenson also invented, or at least improved upon, the cucumber slicer, in his pursuit of the perfect sandwich for his afternoon tea.

IMAGE: George Stephenson’s cucumber slicer, from the Millennium Gallery, Sheffield.

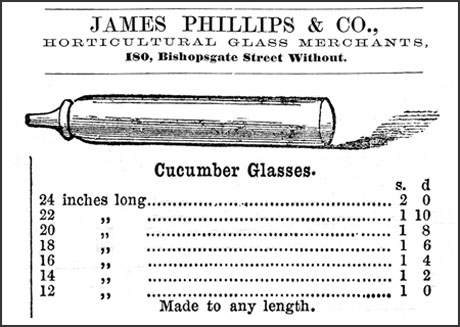

IMAGE: Cucumber straightening glasses advertised in a mid-nineteenth century horticultural catalogue, via the Old Garden Tools museum.

Farmers today use improved, non-bendy varietals, grown on a trellis structure so that gravity helps straighten their cucumbers, but perfectionist Victorian gardeners relied on Stephenson’s blown glass cylinders in order to avoid the kinks that not only make a cucumber harder to slice, but can also affect its taste by restricting water and nutrient passage. It’s a device that embodies the imperatives of economic botany: the aesthetic and biological rationalisation of plants for human use.

A Victorian glass cucumber straightener is just one of the more than 100 such antique gardening tools currently on display at the Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum in the Bronx, alongside mole forks, beet hoes, clod crushers, and wasp catchers.

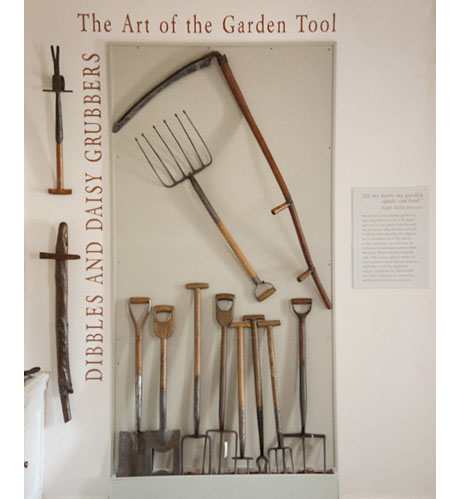

The exhibition, Dibbles and Daisy Grubbers: The Art of the Garden Tool, closes on Sunday, July 1 (meaning, sadly, that I will not have the chance to see it), and represents just a tiny fraction of the 10,000 gardening implements, some of which date back to the 1500s, that landscape architect Mark Morrison has collected over the past thirty-five years.

IMAGE: Antique garden tools on display at the Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum.

The devices on display are organised by function, from seed sowing to pruning and pest control, followed by fruit harvesting and asparagus digging. Some are easily recognisable — a spade is a spade, whether it is today’s assembly-line model with a plastic handle, an elegant lady’s trowel used by Queen Victoria, or a hand-forged, battered, and rusted wood and iron implement from the eighteenth century.

IMAGE: Antique garden tools on display at the Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum.

Others are more obscure, particularly those related to fruit and vegetable cultivation and harvest. Although the keen allotment grower or kitchen gardener might still require them, mechanical, industrial-scale agriculture has for the most part overridden the gastronomical preferences that led the French and English to develop different asparagus knives, one for slicing under the soil to produce a white-stemmed vegetable, and the other for sawing through the spear at the surface, for a springy, green shoot.

IMAGE: Antique garden tools on display at the Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum. Morrison’s collection includes 350 watering cans.

Mechanisation has also made redundant the custom-made nineteenth-century leather lawn boots (seen above), which would have been worn by a horse so that it didn’t harm the grass as it dragged a mower across it.

IMAGE: Antique garden tools on display at the Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum.

But, whether obsolete or simply old, each tool represents an intimate design response that balances the biological and environmental needs of plants with the desires and physiology of humans — they are devices that mediate that domestic relationship, supplementing the limitations of the human body and the shortcomings of environment, defending against the competition posed by pests, and sculpting plant forms to optimise their aesthetic appeal, fruiting potential, and harvestability.

IMAGE: Antique garden tools on display at the Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum.

Together, the story these tools tell is of the ways humans have remade nature (including themselves) — a long and ever-evolving project to terraform the Earth, for subsistence as well as for pleasure.

While walking a New York Times reporter through the exhibition, Morrison explained that, “when he scans his racks of 150 trowels and 350 watering cans, he is reminded of rural subsistence farmers over the centuries and their backbreaking labor and hungry families.”

He can’t help but wonder, he says: “How many people’s lives did these save; how many people did they feed?”

Thanks to Georgia Silvera Seamans (Local Ecologist) for the link — and, if you’re in New York, please check out the exhibition in its final days and let me know what you think.

Previously on Edible Geography: The Agri-Tech Catalogue.