Hot on the heels of my menu donation to the New York Public Library comes this intriguing news story about a team of ecologists using Hawaiian restaurant menus to reconstruct long-term changes in local marine populations. The menus provided the evidence needed to trace historical ecological shifts during “a critical 45-year gap” in the state’s early twentieth-century fishery records.

IMAGE: Menu cover, Monarch Room, Royal Hawaiian Hotel, March 25, 1977. NYPL Menu Collection.

Drawing on library and museum collections, but mostly on souvenirs saved by friends and colleagues, Kyle S. Van Houtan of Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, Loren McClenachan, assistant professor of environmental studies at Colby College, and Jack Kittinger of Stanford University’s Center for Ocean Solutions analysed 376 menus from 154 different restaurants in Hawaii, dated from 1928 to 1974.

The menus, Van Houtan et. al. explain in a peer-reviewed letter in the August 2013 issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, came from “a range of eateries from local businesses to larger restaurants serving tourists (we excluded 60 cruise-ship menus because their pantries were not locally sourced).”

IMAGE: Entrees, Monarch Room, Royal Hawaiian Hotel, March 25, 1977. NYPL Menu Collection.

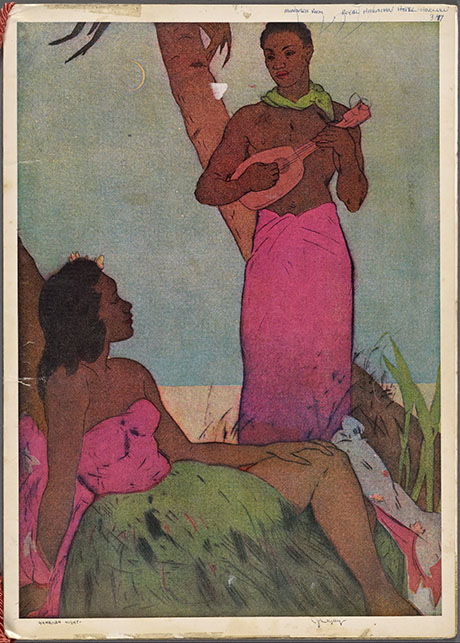

By counting the mentions of different species on the menus over time, the team were able to track a striking decline in Hawaii’s nearshore fishery stocks and an increasing reliance on larger, oceanic species. Reef fish, jacks, and bottomfish went from being extremely common before 1940 to appearing on less than 10 percent of menus by 1959, the year Hawaii became a state. Restaurants filled the gap by serving large pelagic fish, such as tuna and swordfish, which appeared on 95 percent of menus by 1970.

The scientists benchmarked their menu-derived data against early market surveys and later government fishery statistics from either side of the gap in the historical record, giving them confidence that their findings accurately reflected shifts in wild fish populations rather than just consumer preference or culinary trends.

Hawaii, the team admitted, was particularly well suited for their experiment in menu archaeology as historical ecology because “its remote location meant most locally consumed seafood was locally sourced.”

Nonetheless, the menu presence of some species didn’t accurately reflect changes in the marine environment: molluscs and shrimps were mostly imported from the mainland United States, frogs were sourced from local aquaculture operations, and the majority of the islands’ sea-turtle harvest was sold in fish markets rather than restaurants. “These latter instances,” Van Houtan noted, “may still present important information, such as the market forces supporting wildlife harvests.”

IMAGE: Menu occurrence of fishery items follows the rise and fall of local fisheries: wild-caught offshore fish species (top panel), imported and aquaculture species (middle panel), and wild-caught inshore species (bottom panel). Chart from Kyle S. Van Houtan, Loren McClenachan, and John N Kittinger, 2013, “Seafood menus reflect long-term ocean changes,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 11: 289–290.

The team conclude their report by comparing restaurant menu analysis to the archaeological excavation of a midden in terms of its potential contribution to the historical environmental record — an unwitting testament to over-consumption, ecological pressures, and resource shifts. These menus “were often beautifully crafted, date-stamped, and cherished by their owners as art,” Van Houtan added, but “the point of our study is that they are also data.”