During the Edible Archaeology panel at Foodprint NYC, Bill Grimes, former restaurant critic and current obituary writer for The New York Times, briefly referred to “one of the great mysteries for all culinary historians — what did it taste like?”

What did the vegetables that they sold at Washington Market back in 1880 and 1890 taste like? You just go nuts thinking about it because you can’t know.

The issue is that the challenge of flavour reconstruction is not simply biological — combining particular varietals with the appropriate growing conditions — but also contextual.

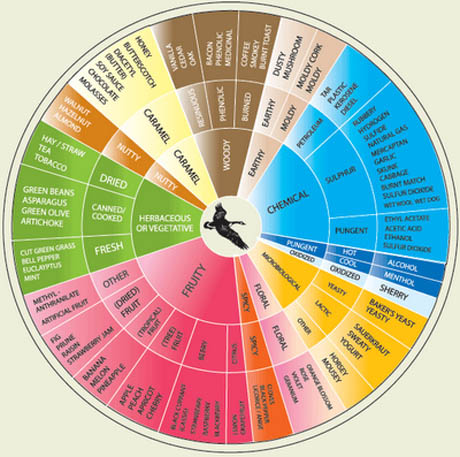

IMAGE: The ubiquitous Wine Aroma Wheel, developed by Ann C. Noble of UC Davis, which both describes and shapes California wines today.

Historical agricultural technologies, processing, storage practices, and preparation styles can, for the most part, be reconstructed, but the sensory and analytical framework through which we taste food, on both a personal and cultural level, shifts over time in ways that we don’t even have the language to describe, let alone recreate.

Nonetheless, two interesting experiments in bio-reconstruction, each with a claim to recreate historical flavour, recently popped up in my reading list. The first comes via architectural historian and wine cartographer David Gissen’s blog, HTC Experiments, and concerns franc de pied wines.

IMAGE: Vineyards in France, Bibliothèque nationale de France, via HTC Experiments.

In the 1840s, a third of the population of France derived a living from wine — the nation’s second most valuable export after textiles, despite the fact that indigenous consumption was an already impressive fifty litres per head (and rising) each year.

“French viticulture,” writes Christy Campbell in The Botanist and the Vintner, had “entered a golden age,” with improved machinery and methods of cultivation as well as the invention of “a convenient glue that fixed paper to glass” and thus allowed producer and place-specific labeling. “Every owner, it seemed, had to have a ‘chateau,'” as wealthy investors created a speculative boom in vineyards and the great wines of Bordeaux and Burgundy began to acquire the characteristics we still value today.

In other words, the stage was set for disaster.

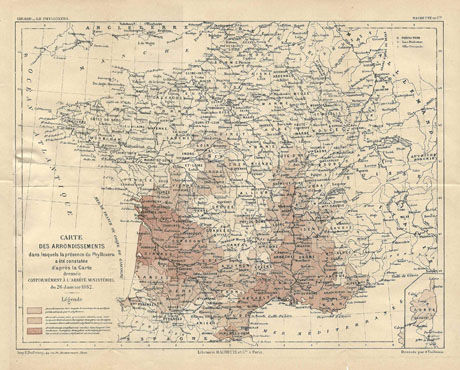

IMAGE: 1882 map showing the advance of phlloxera in France, via Wikimedia.

In 1863, a small wine merchant with a back garden vineyard in Roquemaure, on the right bank of the Rhone, planted some clippings of American vines sent as a gift from a friend. The following summer, his native Grenache and Alicante vines turned yellow, shriveled up, and died. By the 1870s, almost fifty percent of France’s vineyards were destroyed — a scene that would appear “to our contemporary eyes,” Gissen writes, as if “vast stretches of French wine country” had been “chemically attacked or industrially poisoned.”

IMAGE: The lifecycle of phylloxera, via.

The culprit was a tiny aphid-like insect, native to North America and innocently imported on the gifted vine clippings. Called phylloxera vastatrix, the microscopic pest sucked sap from vine roots. The resulting root galls were not fatal to American vines, due to biochemical responses developed over years of co-evolution — but French vines had no such defenses, and succumbed en masse.

The impact on wine culture and French society was enormous, and Campbell’s book (to which I plan to return in a future post) details the enormous lengths — research commissions, quarantine zones, and the invention of chain-mail vine gloves and giant cast-iron syringes for injecting explosive pesticides into the soil — that France’s desperate wine-growers, government officials, and botanists went to in their search for a cure.

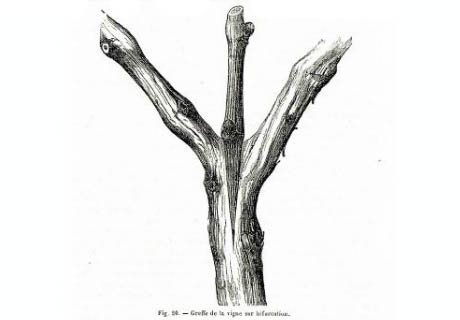

IMAGE: Vine grafting instructions from Charles Baltet’s Arboriculture fruitière et viticulture handbook of 1870, via the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

To make a long story short, however, by the end of the nineteenth century, agricultural officials and scientists had determined that the best way for French viticulture to overcome the phylloxera plague was by grafting French vines onto already resistant American rootstock. The process was called “reconstitution” and, as Gissen points out, it was not without challenges of its own.

Planting such a hybrid, almost Frankenstein-like plant must have been torturous for a nineteenth-century French wine maker. They experienced a panic twice-over: the initial loss of their vineyards and their replacement with “American” root stock. American vines produced notoriously strange-tasting grapes. And French wine-makers must have wondered if the typical (and odd) flavors of American vines would transmit into the French grape.

Many had their fears assuaged when, in spring 1894, white Burgundy from a three-year-old grafted vine won a gold medal at the Paris wine concours. For most, “a grand cru on American roots was still a grand cru,” writes Campbell. But some disagreed, arguing that “wines from grafted plants have by no means the constitution of the old wines,” that they became ready to drink more quickly, but went off more quickly too, and even that certain crus had lost their distinctive characteristics and had taken on a distinctively American “taste of fox.”

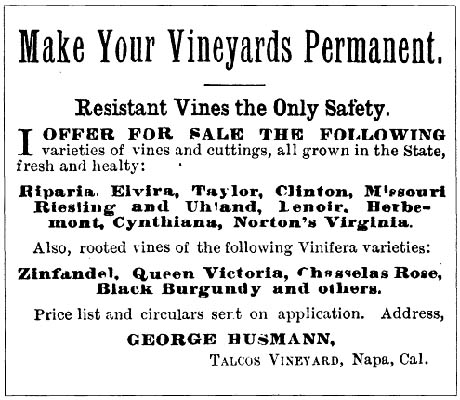

IMAGE: Advertisement for resistant American rootstock, Pacific Rural Press, 1883, via.

If you buy a bottle of wine today, it is almost without exception made from grapes grown on grafted vines.* Almost, because, as Gissen explains, “a small number of French winemakers have attempted to reconstruct nineteenth-century vineyards with new and small plots of ungrafted vines. These latter vines, planted in historically important French wine regions, are called franc de pied.”

The resulting wines are an attempt to recreate the long-lost flavour of pre-phylloxera French wine. These experimental winemakers, and other franc de pied enthusiasts, believe that “French wine lost something when it was forced to graft all of its vines over to American rootstock” — a certain flavour, texture, and even purity.

IMAGE: Pre-phylloxera vines growing in the Benanti vineyard, via the Asia Wine Society.

There is no way to compare the taste of this “bio-historical reconstruction,” as Gissen terms it, to its lost original. Perhaps the closest we can come is a pre-phylloxera Chateau Latour, made in 1863 and sampled by Wine Spectator in 2000. It was described as astonishing in terms of its “purity and clarity on the nose and palate,” with the “texture of finest silk,” aromas of “tobacco, cigar box, leather, berries, plums, and wet earth,” and flavors that “remained on the palate for minutes after each sip.”

IMAGE: Cellars at Chateau Latour, via the Wine Cellar Insider.

“Extraordinary silkiness” seems to be a common characteristic of today’s franc de pied wines, too — but comparing a wine made in 2011 with one that has been aged for more than a century is hardly apples to apples.

More interestingly, Gissen, while acknowledging that we can’t taste history, proposes tasting the difference instead — an experiment that I would also love to try:

I hope to taste a few of these franc de pied wines. But I want to taste them alongside wines made from grafted vines from the same vineyard. Arranging this is not easy. To taste the difference, everything must be identical – soils, vintage, and the techniques used to transform grapes into wine.

•••

IMAGE: Oostvaardersplassen in 2008. Photograph by EM Kintzel, I Van Stokkum.

A few days later, with Gissen’s post fresh in my mind, I read Elizabeth Kolbert’s “Recall of the Wild” in the New Yorker. The article, which is well worth reading in full, tells the fascinating story of Dutch efforts to recreate Europe’s paleolithic ecosystem in a fifteen-thousand acre park built on reclaimed land half an hour east of Amsterdam, within the larger context of the “rewilding” movement.

Oostvaardersplassen, as the Dutch reserve is known, was originally drained in the 1950s and was intended for industrial use until “a handful of biologists convinced the Dutch government that they had a better idea.” They stocked the landscape “with the sorts of animals that would have inhabited the region in prehistoric times — had it not at that point been underwater.”

IMAGE: Heck bull in Germany. Photograph by Walter Frisch.

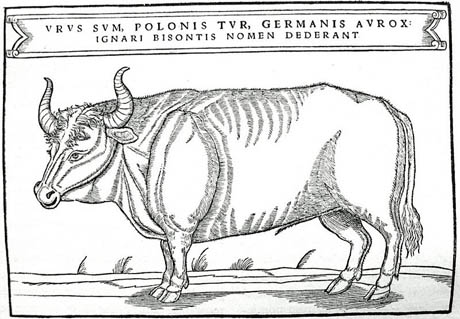

The fact that, in some cases, those animals were now extinct did not deter the biologists. “For example,” writes Kolbert, “in place of the aurochs, a large and now extinct bovine, they brought in Heck cattle, a variety specially bred by Nazi scientists.”

Later in the article, Kolbert visits the nearby TaurOs Programme, a contemporary, de-Nazified attempt to backbreed a more authentic aurochs. The basic idea, she writes, is that:

If different breeds of primitive cattle preserve different stretches of the aurochs’ genetics material then reassembling those stretches should produce something close to — thought not exactly like — the original.

IMAGE: Aurochs, illustrated by Sigismund von Herberstein in 1556, via Wikipedia.

The four-year-old programme expects to generate herds of its new aurochs (which it plans to call a “tauros”) by 2025, at which point, they “expect that large tracts of Europe will have been rewilded and the animals will be allowed to roam across them.” Already, however, they are supporting their research by renting proto-tauroses to nature parks, and — most interestingly, from my perspective — butchering them. To quote Kolbert again:

The meat is marketed as “wild beef,” and it commands a premium in Amsterdam, where it is available only to customers who sign up for delivery in advance.

This gastronomic aspect of rewilding has caught on in recent years, as ecconomically depressed areas across Europe join the movement: Kolbert writes that “it is expected that visitors to the continent’s rewilded regions will be able to enjoy not just the safari-like tours but also the local cuisine.” The chance to eat man-made recreations of a long-lost ecosystem, Diego Benito, who runs a thirteen-hundred acre nature preserve in far western Spain, tells Kolbert, is exactly the kind of story that will sell.

Once again, the authenticity of these historical flavours — and of the new wildernesses they come from — is both a key part of their attraction and an acknowledged impossibility. No one is claiming to be able to recreate an originary wine or an extinct animal — but they are appealing to a powerful nostalgia for a lost pre-modern landscape nonetheless.

In the end, Wouter Helmer, a co-founder of Rewilding Europe, explains to Kolbert that they are “not looking backward but forward,” and that, in the end, whether the landscape they created is a wilderness or not, “it will be wilder than it was, and that’s what matters.”

•••

While acknowledging its appeal, Kolbert concludes her article unconvinced of rewilding’s ultimate viability. Meanwhile, Gissen points out that franc de pied vines, by their very nature, frequently succumb to phylloxera and have to be replanted again, and again. And, as William Grimes (and I) assert at the start of this post, tasting historical flavour is impossible, if only on the level of our own perceptual framework.

Nonetheless — and despite the fact that these kinds of biological reconstructions are all-too-frequently hijacked in the name of pseudoscience or, worse, racists and eugenicists in search of a mythic lost purity — these experiments are important, as much for what they can’t do as what they can.

As Gissen writes, franc de pied wines “dare history as much as they rebuild it.” They and the tauros are what he calls elsewhere an “agitational reconstruction” — a form of historical reflection on contemporary issues.

By proposing an alternate history, this expensive “wild beef” and obscure, extremely silky wine can provoke us to reconsider our own assumptions as to what wine, or the landscape, can and should be. It is historical reconstruction as a method for critiquing the present and re-imagining the future, rather than recapturing the past.

* Curiously, due to its geography and climate, French vines imported into Chile never succumbed to the pest. Christy Campbell, in The Botanist and the Vintner, reports that many Chilean wines take great pride in the fact that they are still grown on “original” French rootstock — but, of course, not on French terroir.