IMAGE: Soil samples (the darker ones are carbon-stained), via.

In the United States, soil protection is typically discussed in terms of erosion. Through a model law disseminated during the 1930s Dust Bowl, states were encouraged to create soil conservation districts with the authority to plan and carry out irrigation, drainage, and erosion control programmes, and this continues to be the standard American framework for soil legislation and protection today.

Meanwhile, under entirely separate legislation, the EPA focuses on remediating contaminated soils through its Brownfields and Superfund initiatives.

IMAGE: Urban farmers at Berlin’s Prinzessinnengärten grow food in mail sacks and plastic crates to avoid soil contamination as well as remain mobile in case the site is redeveloped. Photo by Nicola Twilley.

In Germany, however, as I learned from my foodscape mapping collaborator (and soil expert) Alex Toland, federal soil legislation encompasses not only erosion control and remediation, but also recognises the importance of soil as “an archive of natural and cultural history.”

The soil, in other words, is not simply a natural resource, but also a memory bank of sorts — an evolving record of accretion, erosion, contamination, and manipulation that bears witness to processes occurring on timescales as radically different as continental drift and human inhabitation.

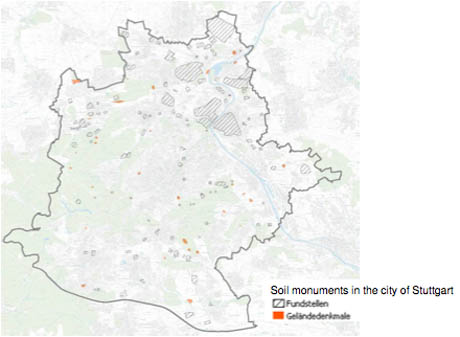

IMAGE: Stuttgart mapped according to its archaeological sites (Fundstellen) and soil monuments (Geländedenkmale).

According to Alex, the soil archive clause is rarely invoked, although it has been used to protect a couple of Neolithic sites. However, as this inventory of Stuttgart’s soil archive [PDF] makes clear, the law does indeed define soil as a repository of “information about specific conditions of soil formation in the past or information about human culture and agriculture” — which means that, sealed beneath the pavements of the city, are hundreds of protection-worthy “soil monuments” that include everything from rare geological formations to areas of increased phosphate levels that trace former cattle yards.

IMAGE: Rubble map of Berlin by Alexandra Regan Toland in collaboration with Prof. Dr. Gerd Wessolek, as installed at the Altes Museum Berlin-Neukölln in September 2010.

In Berlin, Alex has created her own soil memory maps, focusing in particular on sulphate leaching from the city’s post-World War II rubble mountains. In the aftermath of heavy Allied bombing, Berlin was covered in more than 75 million cubic meters of rubble and debris that had to be “cleared, sorted into recyclable and non-recyclable material, and moved to suitable storage and dumping sites before the city could begin rebuilding.”

IMAGE: Rubble women at work in Germany’s ruined city centres; photo via Der Spiegel.

The work was mostly done by women, called “Trümmerfrauen” or rubble women, who dismantled the city’s ruined buildings and piled them up into artificial hills in Berlin’s public parks, according to reconstruction plans drafted by architect Hans Scharoun and colleagues. As Alex explained, Berlin is in a glacial spillway, washed flat by meltwater, so its rubble hills — particularly the 80-metre tall Teufelsberg — significantly redefined Berlin’s topography.

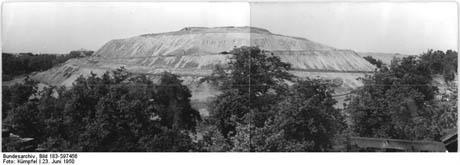

IMAGE: The rubble mountain in Volkspark Freidrichshain, photographed in 1950, via.

IMAGE: Teufelsberg today, and a rubble mountain soil section; photographs by Alexandra Regan Toland.

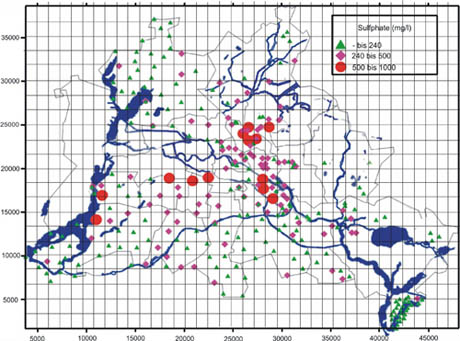

Now, sixty years later, the rubble mountains form a lesser-known monument to the war, an archive of shattered bricks, tiles, and mortar covered with secondary forest that is slowly leaching sulphate into the city’s waterways.

IMAGE: Elevated sulphate levels in Berlin’s soil trace the chemical’s water-borne spread from the gypsum mortar and plaster entombed in the city’s rubble mountains. Map included in Alexandra Regan Toland’s rubble mapping installation.

IMAGE: Rubble map of Berlin by Alexandra Regan Toland in collaboration with Prof. Dr. Gerd Wessolek, as installed at the Altes Museum Berlin-Neukölln in September 2010.

In a city filled with memorials, the soil offers a different perspective: re-framing the environment as an ongoing co-production of both human and natural activity rather than a series of wars and walls.

Previously on Edible Geography: Sweet and Sour Soils and The Dust of Our Ancestors.