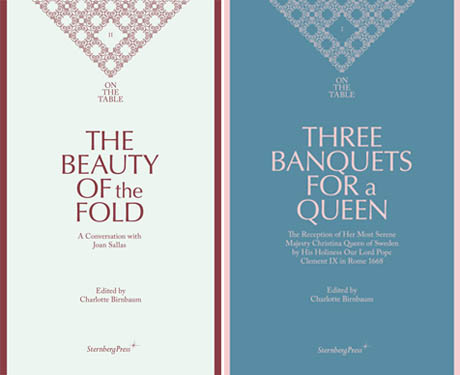

For the second in her lovely “On the Table” series exploring “the encounter between food and art,” writer Charlotte Birnbaum has focused on the overlooked riches of European napkin-folding culture.

IMAGE: The covers of the first two books in Charlotte Birnbaum’s On the Table series, published by Sternberg Press (distribution seems to be relatively limited, although signed copies are available to buy or order at McNally Jackson).

In The Beauty of the Fold, an extraordinarily gorgeous little book, Birnbaum shows that, contrary to popular belief, folding is not a Japanese invention. Instead, the “earliest instruction manual for the artistic folding of napkins” was published in 1639, as part of Le tre trattati, a series of treatises on the culinary arts written by Matthia Gieger, a German who worked as a meat carver in Padua and who “learned the art of napkin folding so well that he taught the subject at the University of Padua on the side.”

IMAGE: A meat carving diagram from Matthia Gieger’s Le tre trattati (in German translation), via A Little History of Carving.

It is quite astonishing to read about the golden age of European napkin folding, when “Nuremberg was the home of an entire school devoted to the art,” butlers had shelves of “how-to” manuals to stay up-to-date with the rapid pace of fold innovation, and Samuel Pepys paid an expert 40 shillings to teach his wife the craft.

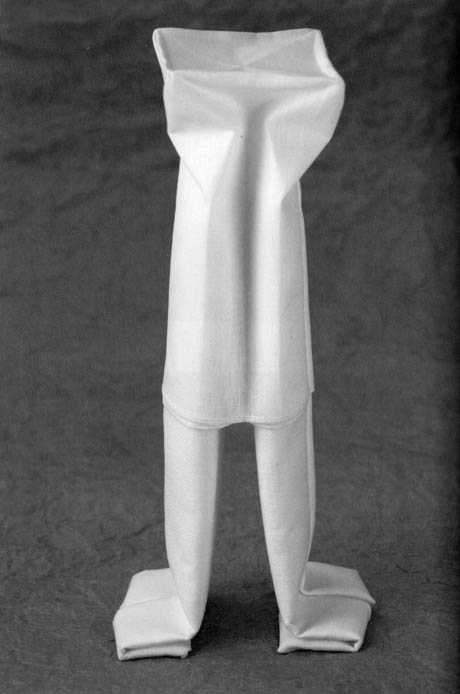

IMAGE: The Watchtower, a member of the obelisk family of folds, dates back to a fashion for architectural forms in napkin folding from the baroque era onwards (from Sallas and Birnbaum’s illustrated and annotated catalogue of the nine folding families in The Beauty of the Fold).

As Birnbaum explains, napkin-folding culture “evolved in close dialogue with the elaborately pleated clothing of the Renaissance and the culinary extravagances to which the garments were worn,” reaching its zenith in the early Baroque:

The napkins, frequently perfumed with rose water, were not only used to protect clothing and to wipe one’s mouth: the eye-catching folded fabric was often designed to accommodate other decorative and utilitarian elements of the table, like place cards, menus, and toothpicks. Or to present eggs, sweets, or bread rolls in an elegant and playful manner. Sometimes beautiful songbirds were hidden in the napkins to charm the guests as they, twittering and fluttering their little wings, made their delightful escape.

At grand banquets such as coronation celebrations, the importance was not so much on taste and appetite as on ingenuity and display; the meal was not intended to feed so much as delight the senses and impress the guest with the host’s wealth and status.

IMAGE: The Dutch Bonnet, a member of the cap family of folds, is still used on the royal tables of Queen Elizabeth II (from Sallas and Birnbaum’s illustrated and annotated catalogue of the nine folding families in The Beauty of the Fold).

By the eighteenth century, Birnbaum writes, these folded table sculptures, and their equally transient decorative companions — wine fountains, marzipan statues, and sugar fantasies — had begun to be replaced by porcelain decorations.

However, in addition to providing an illustrated catalogue of the nine folding families (blintzes, caps, fans, layers, lilies, obelisks, rolls, sachets, and twins), Birnbaum also interviews a contemporary napkin folding artist, Joan Sallas, who is bringing this “cultural fossil” to life.

IMAGE: A whale napkin illustration from Matthia Gieger’s Le tre trattati, via A Little History of Carving.

IMAGE: A porcelain whale used as table decoration, made c. 1750, by the Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, via A Little History of Carving.

Sallas, a Catalan artist who came to Germany to work as a cartoonist, fell into napkin-folding after a contract to illustrate three yoyo-trick books gave him the idea to pitch one on how to fold. Despite the fact that the resulting book was a commercial disaster, he tells Birnbaum that he “had so much fun that I decided to change my profession, and, since 2000, I’ve been a professional folding artist.”

Sallas trained himself by re-reading obscure treatises and reverse-engineering the napkin sculptures he found in historical banquet descriptions, and dreams of opening a folding museum “somewhere in Europe.”

IMAGE: The Basic Rose, a member of the blintz family of folds, was part of series of symmetrical forms inspired by Fröbel Blocks used in the first kindergartens (from Sallas and Birnbaum’s illustrated and annotated catalogue of the nine folding families in The Beauty of the Fold).

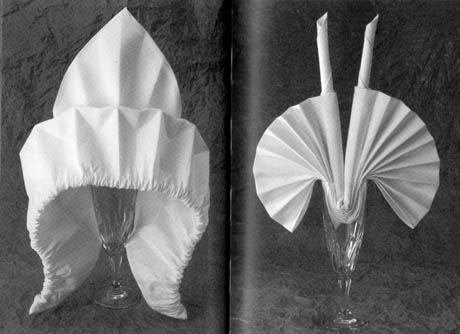

IMAGE: The Mother Hubbard and The Stanley, members of the fan family of folds, are named after a nursery rhyme and an explorer respectively (from Sallas and Birnbaum’s illustrated and annotated catalogue of the nine folding families in The Beauty of the Fold).

However, his folding is not simply a revival of lost traditions: Sallas tells Birnbaum that the art of the fold is currently “undergoing huge developments,” as an understanding of the possibilities of the form can be used to “build an airbag or satellites, research DNA, discover new medications, question Euclidean mathematics, reproduce philosophical thought.” His own ambitions include developing “the erotic and even pornographic side of the art of folding,” complete with a “dance of the seven folded napkins.”

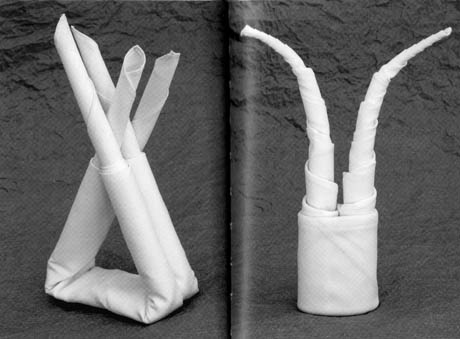

IMAGE: The Rifle Pyramid and The Ram, members of the roll family of folds, were invented by Heinrich L. Fritzsche while working in a canteen during the Franco-Prussian war, “where he had time to develop napkin-folding models.” (From Sallas and Birnbaum’s illustrated and annotated catalogue of the nine folding families in The Beauty of the Fold.)

Watching Sallas fold, as you can online, is curiously hypnotic: he admits that it “can be somewhat boring, especially when practicing and repeating the same folds,” and yet there is also what Birnbaum calls an “almost mystical moment” when the form emerges.

VIDEO: Joan Sallas shows how to fold a water lily napkin as part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Vienna Circa 1780: An Imperial Silver Service Rediscovered exhibition in 2010.

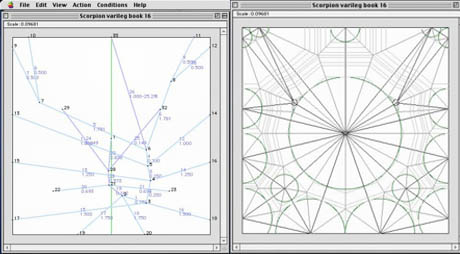

IMAGE: The design screen and computed crease pattern for a folded scorpion in TreeMaker, a software created by physicist Robert Lang.

In a era when folding software allows almost anyone to prototype new designs almost instantaneously (leading to what origami enthusiasts called the Bug Wars of the 1990s, when folders competed to create paper models of ever more complex species), this slim and beautifully designed book is a wonderful reminder of a lost European tradition of napkin folding, and its origins in gastronomy.