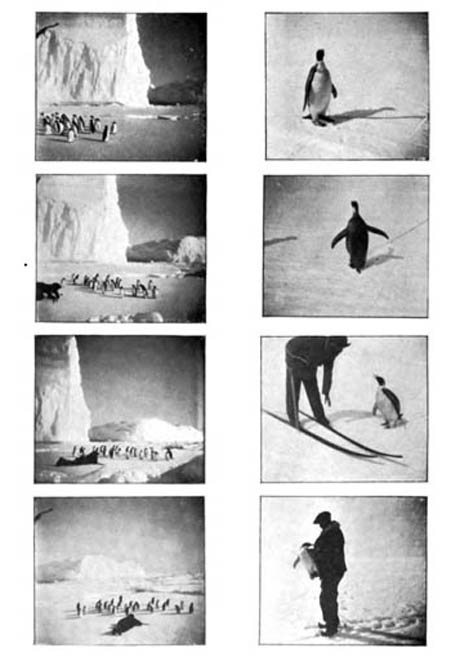

IMAGE: “Penguin Interviews,” from Frederick Cook’s Through the First Antarctic Night, 1896-1899, via Peter Smith, Food & Think.

Very good news: my former colleague at GOOD, Peter Smith, has joined the Smithsonian’s Food & Think blog as a regular contributor. Among his early posts is this one, on a highly effective scurvy prevention technique pioneered by Frederick Cook, an American surgeon and polar explorer.

Cook’s achievements have been overshadowed by his controversial claims to have been the first man to reach the North Pole as well as the first to climb Mt. McKinley. Nonetheless, as a member of the first expedition to spend an entire, dark winter icebound in the Antarctic, Cook’s innovations included recommending that the Belgica crew members sit in front of hot, bright fires to counteract the as-yet-unnamed Seasonal Affective Disorder, pioneering sled and tent designs, and the eating of penguins to ward off scurvy.

The latter was a trick that Cook had learned from the Inuit during his earlier expedition to the Arctic. While other Westerners had certainly noticed that the Inuit thrived despite their lack of access to antiscorbutics such as citrus fruits or cabbage, Cook was the first to realise that their secret lay in eating fresh meat, raw or lightly cooked, rather than the canned fish balls and sausage hashes with which the Belgica was provisioned.

Smith quotes a recent paper, “The Importance of Eating Local: Slaughter and Scurvy in Antarctic Cuisine” by Jason C. Anthony, on the taste of penguin, which Cook compared to “a piece of beef, odiferous cod fish and a canvas-backed duck roasted together in a pot, with blood and cod-liver oil for sauce.” On the other hand, Roald Amundsen, a fellow crew member, declared it “excellent,” but recommended the smaller fourteen-pound Adelie penguins over the much larger Emperor penguins, and warned that “you must ensure that all the fat is cut off the meat. It does not need to be treated with vinegar to make it taste good; you simply take the meat as it is and fry it in a pan with a knob of butter.”

Anthony’s paper contains many more fascinating details on penguin egg omelettes and penguin-fried seal steak, and is well worth a read. Meanwhile, Smith’s post explores the curious method the crew of the Belgica developed to hunt the poor birds: playing a tune on the ship’s cornet to lure them in, and then seizing them alive. The image this conjures up, of a sponge-gummed, half-mad sailor playing the cornet on an ice-bound boat in the dark, as penguins gather round solemnly to listen, is almost unbearably sad and strange.

Read Smith’s post in full to discover the musical preferences exhibited by the penguins, and keep an eye on his forthcoming contributions to Food & Think.