IMAGE: William and Kate’s official royal wedding cake.

The British fruit cake may not taste quite as delicious as Prince William’s favourite chocolate biscuit cake, but its alcohol-soaked sultanas and rock-solid royal icing give it an impressive shelf-life and the sturdiness to survive extensive handling — two qualities much more necessary to the core functions of a traditional wedding cake.

The one served at the newly minted Duke and Duchess of Cambridge’s wedding earlier today is already five weeks old — the time it took to create the sugar paste flower decorations — while the bottom layer formed a foundation solid enough to bear the weight of seven more tiers above.

But fruitcake’s robust longevity is also essential to the wedding cake’s post-ceremony afterlife, in which it is distributed by mail as a token to those who were unable to attend or who were not quite important enough to receive an invitation. This post-event cake-posting is a long-standing tradition, as evidenced by this New York Times report on a disturbing spate of lost cake boxes back in 1894:

Complaints have recently been made that when wedding cake is sent by mail it rarely reaches its destination, and it is generally supposed that it is appropriated and eaten by the Post Office clerks. Whether the latter accusation be true or not, it is certainly true that when a piece of wedding cake is intrusted to the English Post Office the chances are that it will never reach its destination.

IMAGE: A slice of Charles and Diana’s wedding cake, as mailed.

IMAGE: Charles and Camilla’s wedding cake was mailed in a tin, rather than the customary cardboard box.

Although William and Kate’s cake is destined to end up in fragments dispersed across far flung Commonwealth countries, its ingredients were as British as possible (the oranges, spices, and ginger paste all had to be imported).

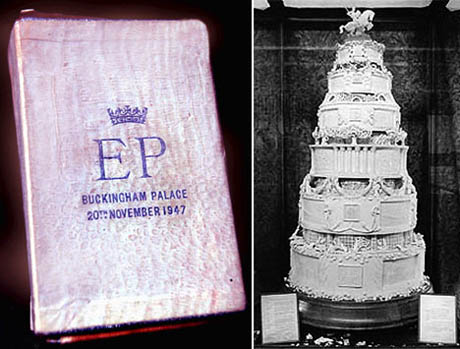

By contrast, in 1947, Princess Elizabeth and Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten’s nine-feet high, 500 lb fruitcake was christened the 10,000 mile Wedding Cake: its ingredients were donated by the Australian Girl Guides. An entire tier of the cake was sent back down under in gratitude, while other Commonwealth countries and colonies, as well as institutions around the United Kingdom, made do with a representative slice.

IMAGE: Cake ingredients from Australia were gratefully received in a heavily rationed post-war Britain.

IMAGE: Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten’s cake was widely distributed in slice form.

A surviving slice of Queen Victoria’s wedding cake, preserved since 1840, was put on display at Windsor Castle in 2007. Librarian Jane Roberts noted that it seemed “mummified rather than actually decayed.” The box was one of thousands distributed as souvenirs: “Victoria was related to all the royal families of Europe,” and, apparently “all would have expected a piece.”

IMAGE: A 167-year-old slice of royal wedding cake, preserved in its original mailing box.

This is fruitcake as statecraft: its lack of palatability reflective of its function as symbol rather than food. Cementing Commonwealth ties and salving snubbed dignitaries alike, the mailable wedding cake distributes royal favour across the globe. And if you’re a postal worker, it might be worth stealing for its future auction value, if not for its taste.

***Update: 28/08/11***

A distinguished reader was honoured with her very own slice of Will and Kate’s cake, and kindly sent Edible Geography a picture of the tin. “Unfortunately,” she confessed, “we had already eaten the cake for tea that day before it occurred to me that I should have photographed it too.” A girl after my own heart…