IMAGE: Garden show display advertising “super atomic energized seeds,” photo by Frank Scherschel for Life, 1961, via Pruned

At her blog, Garden History Girl, Paige Johnson (by day, a nanotechnology researcher at the University of Tulsa), describes the inception of the Atomic Gardening Society:

In March 1959, an unusual group of scientists, government officials, and lesser worthies assembled for a dinner party in the dining hall of the Royal Commonwealth Society, London. Unbeknownst to them, one of the courses was a strange strain of American peanuts: ‘NC 4x,’ ‘North Carolina 4th generation X-rayed’ peanuts, produced from seeds that had been exposed to 18,500 roentgen units of x-rays in order to induce mutations. The irradiated peanuts were unusually large — big as almonds, according to those in attendance, outshowing the British groundnuts served alongside — and had reached the dining table through the generosity of their inventor Walter C. Gregory of North Carolina State College, who sent them as a gift to Mrs. Muriel Howorth, Eastbourne, enthusiast for all things atomic.

Disappointed with the reaction of her guests, who were less than appreciative of the great scientific achievement present at table, Muriel afterwards “began inspecting [the] uncooked nuts wondering what to do with them all … I had the idea to … pop an irradiated peanut in the sandy loam to see how this mutant grew.” The “Muriel Howorth” peanut (for she had already named it after herself) germinated in four days and was soon two feet high. She called the newspapers.

Shortly thereafter, in a blaze of enthusiasm, Muriel formed the Atomic Gardening Society (with herself as president) and even published a how-to-guide, Atomic Gardening, in order to “co-ordinate and safeguard the interests of ATOMIC MUTATION EXPERIMENTERS who would work as one body to help scientists produce more food more quickly for more people, and progress horticultural mutation.”

As Johnson explains, this interest in using nuclear radiation in plant breeding to induce helpful mutations “grew out of post-WWII efforts to use the colossal energy of the atom for peaceful pursuits in medicine, biology, and agriculture. ‘Gamma Gardens’ at national laboratories in the US as well as continental Europe and the USSR bombarded plants with radiation in hopes of producing mutated varieties of larger peanuts, disease resistant wheat, more sugary sugar maples, and African violets with three heads….”

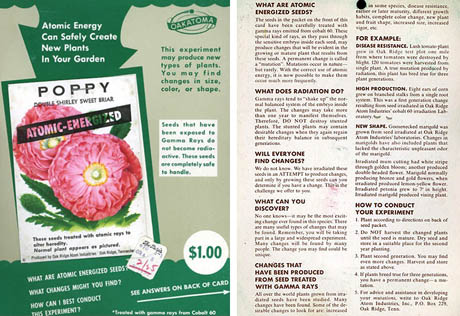

IMAGE: An atomic seed packet, provided by Paige Johnson, via Pruned.

IMAGE: Atomic seeds on sale, photo by Frank Scherschel for Life, provided by Paige Johnson, via Pruned.

Following from his own week of atomic tourism, tracing the ruins and erasures of Nike missile sites that encircle Chicago, Alexander Trevi of Pruned has posted a lengthy and fascinating interview with Johnson, on her continuing efforts to research this neglected piece of nuclear history. In it, Johnson explains that, aside from its obvious retro-futuristic appeal, the story of the Atomic Gardens is particularly compelling for its citizen science component, as well as its potential to offer a historical perspective on the inflated claims of GM-boosters today.

As she points out, “It’s clear from reading the primary sources that most people involved were deeply sincere. They really thought their efforts would eradicate hunger, end famine, prevent another war.” These are eerily similar claims to those we hear from the Gates Foundation, for example, as they pour millions into the development and propagation of transgenic Golden Rice and BioCassava Plus.

IMAGE: “Normal” dwarf tomatoes growing alongside “atomic energized” dwarf tomatoes, photo by Frank Scherschel for Life, via Pruned.

In addition to encouraging a necessary scepticism in our contemporary debate, the story of the atomic gardens also provides a positive example of the value of transparency and public engagement in the debate over altered crops. As Johnson explains to Pruned:

I think one way that science has failed the public is by not making its results accessible, often with the implicit — even explicit — excuse that non-scientists somehow aren’t smart enough to understand them, which is self-serving tosh. It’s interesting that public engagement was desired, and sought out, during the Atoms for Peace program of which the atomic gardens were a part. It was a time when the atomic scientists who had been sequestered during the war began to speak strongly into the public sphere about their science and its implications, to enter the cultural discussion in the way that these atomic experiments — which are still ongoing — should now.

The story of these citizen-pioneers of mutagenesis (the technical term for creating genetic change through the application of chemical, physical, and biological agents) is full of fantastic details, from Muriel Howorth’s propagandising ballet-mime, Isotopia, which involved a cast of Knowledge, Electron, Proton, Neutron, Rat, and Cow, as well as a working geiger counter, to Tennessee-based atomic entrepreneur C.J. Speas irradiating trays of seedlings into his backyard bunker.

IMAGE: C.J. Speas giving a tour of his radioactive bunker to high school students, photo by Grey Villet for Life, via Pruned.

IMAGE: Speas with a tray of irradiated seedlings, photo by Grey Villet for Life, via Pruned.

Perhaps the most bizarre detail in the interview, however, is the news that these gamma gardens are still in operation, relatively unchanged in design since the 50s, in the grounds of national laboratories today. Their circular form, which, as Johnson notes, bears more than a passing resemblance to the atomic danger symbol, “was simply based upon the need to arrange the plants in concentric circles around the radiation source which stood like a totem in the center of the field.”

It was basically a slug of radioactive material within a pole; when workers needed to enter the field it was lowered below ground into a lead lined chamber. There were a series of fences and alarms to keep people from entering the field when the source was above ground. The amount of radiation received by the plants naturally varied according to how close they were to the pole.

So usually a single variety would be arranged as a ‘wedge’ leading away from the pole, so that the effects of a range of radiation levels could be evaluated. Most of the plants close to the pole simply died. A little further away, they would be so genetically altered that they were riddled with tumors and other growth abnormalities. It was generally the rows where the plants ‘looked’ normal, but still had genetic alterations, that were of the most interest, that were ‘just right’ as far as mutation breeding was concerned!

Over at GOOD, Peter Smith recently described a similar layout at the still-active Institute of Radiation Breeding, in Hitachiohmiya, Japan, which has “has a 88.8 Terabecquerel Cobalt-60 source, ringed by a 3,608-foot radius Gamma field (the world’s largest), and a 28-foot high shield dike around the perimeter.”

IMAGE: A gamma garden at Brookhaven National Labs, New York, c. 1958; image provided by Paige Johnson, via Pruned.

IMAGE: Aerial view of the Institute of Radiation Breeding, Hitachiohmiya, Japan.

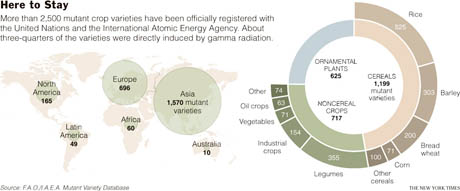

As it turns out, far from being a fantastic fossil from the future that never was, along with jetpacks and flying cars, atomic gardening is alive and well today. According to a 2007 New York Times story, which quotes Dr. Pierre Lagoda, head of plant breeding and genetics at the International Atomic Energy Agency, radiation breeding is actually experiencing a renaissance, due to the introduction of “new methods that speed up the identification of mutants.”

IMAGE: Mutant crop varieties mapped by The New York Times.

What’s more, the Times adds, nearly 2,000 gamma radiation-induced mutant crop varieties have been registered around the world, including Calrose 76, a dwarf varietal that accounts for about half the rice grown in California, and the popular Star Ruby and Rio Red grapefruits, whose deep colour is a mutation produced through radiation breeding in the 1970s. Similarly, Johnson tells Pruned that “most of the global production of mint oil,” with an annual market value estimated at $930 million, is extracted from the “wilt-resistant ‘Todd’s Mitcham’ cultivar, a product of thermal neutron irradiation.” She adds that “the exact nature of the genetic changes that cause it to be wilt-resistant remain unknown.”

IMAGE: “Pierre Lagoda, the head of plant breeding and genetics at the International Atomic Energy Agency, showing mutated plants at a greenhouse in Austria,” photo by Herwig Prammer for The New York Times.

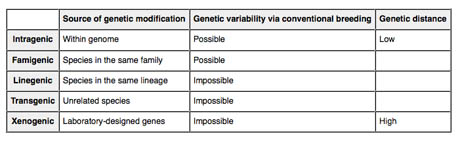

What’s so intriguing about all of this, in terms of the current debate on “Frankenfoods,” is that mutagenesis helps add some much-needed shades of gray to the idea of genetic manipulation. Speaking to The New York Times, Dr. Lagoda is quick to point out that unlike Monsanto’s biotechnologists with their insertion of primrose genes into soybean DNA, he is “not doing anything different from what nature does.” Meanwhile, as Zackery Denfeld of the Center for Genomic Gastronomy pointed out to me over email, “partisan pro-GM advocates rely on the rhetorical stance that mutagenesis is non-directed and thus much more dangerous than transgenesis.” And, just for context, it’s always worth remembering that our orange-coloured carrots and leafy kale are already the result of intentional genetic design, carried out through centuries of selective breeding.

IMAGE: A new classification system for various types of genetically modified organisms proposed by scientist Kaare M. Nielson, via.

In fact, attempts to classify degrees of genetic mutation, from conventional breeding all the way to the creation and insertion of artificially synthesised genes, are the subject of continuing debate, which is heightened by the significance of particular labels in consumers’ minds and the resulting economic impact.

For example, a mutagenic Ruby Red grapefruit grown without the use of pesticides can be labeled as organic and thus be sold for a premium, despite the fact that organic foods by definition cannot be genetically modified. Meanwhile, in Europe, where genetically modified crops are banned, some researchers have argued that disease-resistant strawberries produced through cisgenesis (in which new varietals are created by artificially transferring genes between organisms that could — but haven’t — bred “naturally”) should be allowed to enter market in the same way as conventional crops, as opposed to being regulated as GMOs.

IMAGE: Cisgenesis Volume 1: The Social Life of Scientific Nomenclature, edited by Zachery Denfeld and designed by Tara Kelton and Lauren Francescone, available for purchase at the Center for Genomic Gastronomy.

Denfeld has actually created a remarkable book that documents “every change on the Wikipedia page for Cisgenesis from when it was first created at 22:48 on February 22, 2009, until 16:31 on November 4, 2010,” as a way to explore the shifting ground between “natural” and “artificial” that lies at the heart of this debate.

With his Center for Genomic Gastronomy, Denfeld also creates provenance maps and recipes for transgenic foods; meanwhile, fellow biohackers at Genspace, the world’s first government-compliant community biotech lab, have been inserting jellyfish genes into yogurt using nothing more than a plastic salad spinner and Ziploc bags. These noble efforts, perhaps, are the twenty-first century version of Paige Johnson’s backyard atomic gardeners: solo enthusiasts whose work attempts to draw the conversation around advances in plant breeding technology out from behind the closed doors of private enterprise and into the public realm, where it belongs.

NOTE: I highly recommend visiting Pruned to read Trevi’s interview with Johnson in full — there are many more amazing images and details. Thanks also to Peter Smith and Zackery Denfeld for the email conversation. And if you’re in London, don’t miss Paige Johnson’s talk at the lovely Garden Museum on June 7th.