Over at the Glass House Conversations website, BLDGBLOG’s Geoff Manaugh has posed an interesting question, inviting speculation on the opportunities and pitfalls that might emerge as twenty-first century cities flex their geopolitical muscles in an increasingly urban world. The responses thus far are fascinating, with casual yet mind-blowing references to the unifying powers of sewage systems and the ways in which capital markets redefine perceptions of both time and geography.

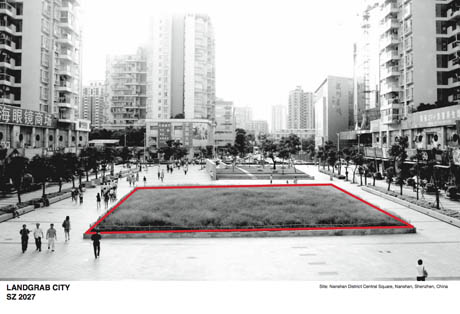

IMAGE: Nanshan district central square, Shenzhen, before Landgrab City’s installation. All photos and images courtesy Joseph Grima, unless otherwise attributed.

IMAGE: Landgrab City installed as part of the 2009 Shenzhen-Hong Kong Architecture and Urbanism Biennale.

Reflecting on this question has also prompted me to post about another wonderful project from the 2009 Shenzhen-Hong Kong Architecture and Urbanism Biennale: Landgrab City by Joseph Grima and Jeffrey Johnson with José Esparza.

Their installation consisted of a “decent-sized field” of roughly 750 sq. metres, Grima explained, placed in the middle of a large and relatively featureless concrete plaza in one of Shenzhen’s busiest shopping areas. Within the field, small plots contained potatoes, cabbages, and banana trees, all carefully planted and tended by one Mr. Yang, “who runs a landscaping firm” in the city.

IMAGE: Mr. Yang, who was responsible for almost all aspects of planting and growing the crops in Landgrab City.

But, despite its bucolic appearance, Grima is quick to point out that “this project doesn’t belong in the category of ‘urban farming’ proposals.” Instead, “it’s simply an attempt to portray, in the most comprehensible and unequivocal manner we could think of, the extent of the city’s true spatial footprint, a concept that is generally pretty alien to its inhabitants.”

In other words, in Landgrab City, Grima, Johnson, and Esparza have created an accurate scale model of how much farmland it actually takes to feed the city of Shenzhen, rather than a 3D billboard for the benefits of urban agriculture along the lines of San Francisco City Hall’s Victory Garden. (In fact, seeing the sheer quantity of agricultural land required to fulfil the city’s dietary needs might somewhat dampen the spirits of those urban farmers who cherish idealistic visions of self-sufficiency.)

In one corner of the field, a 30 metre² satellite photo of Shenzhen represents the city’s estimated geographic footprint in 2027, based on population growth predictions. The date was chosen because 2027 is the year China is expected to overtake the US as the world’s leading economy.

IMAGE: On top of Shenzhen, in Landgrab City. According to Grima, the installation “seemed to be particularly popular among parents with small children — you’d often see young mothers and fathers pointing to the different plants. Since Shenzhen underwent explosive growth in recent decades, many of the city’s inhabitants were probably born or grew up in the countryside, and are probably quite familiar with these plants. Their children, however, are born in the city and have likely never seen a tomato plant or a potato growing in the ground — so the installation has become a kind of involuntary botanical gardens destination within the neighbourhood. Another unexpected and amusing phenomenon illustrates the Chinese relationship with green space within the city. Anything that is green seems to be perceived as a latrine of sorts, and on several occasions we saw parents encouraging small children to relieve themselves on the plants. They probably thought they were contributing to the cause through fertilization.”

IMAGE: An aerial view of Landgrab City.

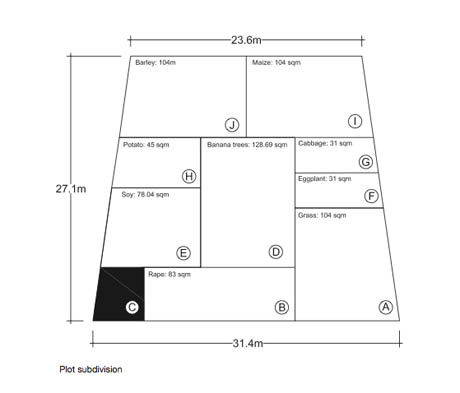

But although it is spectacularly large, this photo only occupies four percent of the field. The other ninety-six percent is divided into carefully calculated plots filled with different types of crops and pasturage. The exact size of each plot is based on how much land it will take to grow the volume of each type of food consumed by the people of Shenzhen in 2027.

For example, 129 m² or about eighteen percent of the total installation is devoted to growing fruit, including apples, mandarin oranges, bananas, and grapes. Another 105 m², or 14.5%, represents the livestock pasturage required to put beef, butter, lamb, and goat onto plates throughout the future city.

IMAGE: Diagram of plot subdivisions from the Landgrab City proposal.

IMAGE: Mandarin oranges growing in Landgrab City.

What this means, then, is for every square metre of “actual” city, the Shenzhen of 2027 will require twenty-four square metres of farmland. Just to give a sense of the scale this implies: to feed a single Chinese city that is 2,050 km² (Shenzhen’s current geographic area, according to Wikipedia), according to these calculations, you would have to devote every single square metre of an area of land the size of, say, The Netherlands and Cyprus combined, entirely to agricultural production.

The process of generating these numbers was one of the most interesting aspects of the project:

José [Esparza] created an incredible spreadsheet into which data for any city can be inserted and the extent of the city’s footprint (divided by crop type) is instantly crunched. All sorts of variables are taken into account, and most of these are available on the FAO’s website and other UN sources: not just quantities of food consumed, but also fertility coefficients (how much land is needed in a given climate to grow a tonne of a certain crop), and consumption patterns in the city as opposed to the countryside.

IMAGE: Pasture in Landgrab City.

Of course, as Grima is quick to point out, the figures generated by this agricultural footprint calculator are extrapolations based on predictions, and thus are “probably only accurate to within +/-15%.” The larger point of the exercise, though — re-imagining the geographic footprint of the city to include its agricultural hinterland — is not only valid but also incredibly interesting, particularly when considered within the context of two twenty-first-century geopolitical trends.

One of these, as implied at the start of this post, is that during first decade of this century, humanity passed a tipping point, becoming a majority urban species for the first time in our history. According to United Nations estimates, just over half of the world’s population lives in a city right now, a proportion that is expected to increase to two-thirds by 2050.

Such a shift in scale naturally creates new challenges and opportunities, prompting an evolution in our understanding of what cities can do, how they should be defined, and, in turn, how they relate not only to each other but to national governments, transnational corporations, and the countryside around them.

IMAGE: Landgrab City, showing crop subdivisions.

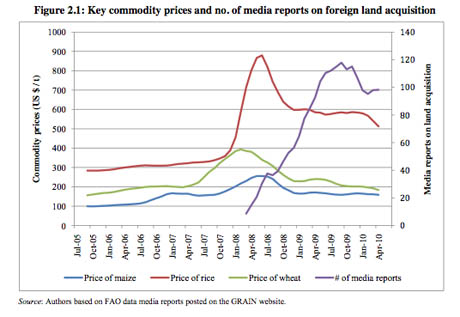

The other geopolitical trend, as referenced in the title of Grima’s installation, is the global landgrab phenomenon: the flurry of transactions in which nations and corporations have purchased large chunks of arable land overseas during the last couple of years.

Although landgrabbing itself is nothing new — think of the Roman Empire, Columbus and the New World, or the Great Powers’ scramble for Africa — its recent popularity as a legitimate financial investment has resulted in a stream of newsprint, scholarly analysis, and reports on the subject.

The logic of stealing land is at least familiar, but what does it mean for a country or — more bizarre yet — a hedge fund to buy and own hundreds or thousands of hectares of another nation state’s territory?

IMAGE: Model of Landgrab City, illustrating the overseas sources of Shenzhen’s food supply.

For example, one of the most widely reported (although ultimately unsuccessful) landgrab examples was Daewoo’s attempt to purchase a ninety-nine-year lease to grow corn and other crops on 1.3 million hectares of farmland in Madagascar — half the country’s total arable land. The 2008 deal was initially seen as quite a coup for the South Korean company, with spokesman Hong Jong-wan boasting to the Financial Times that “food can be a weapon in this world,” and explaining that Daewoo could “either export the harvests to other countries or ship them back to Korea in case of a food crisis.”

Meanwhile, the U.N.’s World Food Programme actually runs school-feeding schemes for children in Madagascar, where a seventy-percent poverty rate creates hunger and nutritional deficits. The resulting popular protests eventually forced the Malagasy president from office, and his successor cancelled the deal.

But a curious and telling detail, as reported by Joseph Grima, is that “had the the deal gone ahead, Daewoo would have paid no importation tax to bring the rice grown in Madagascar back into South Korea, meaning that it is effectively considered “internal production.”

South Korea was not simply outsourcing its food production (which it already does, importing at least fifty percent of its food supply); instead, it was redefining its national territory to include the agricultural prostheses on which its people depend.

IMAGE: Graph showing key commodity prices correlated with media reports on the landgrab phenomenon, from a World Bank report on the subject issued last month.

Most aspects of the landgrab phenomenon are fascinating, from the sheer scale of the deals (the World Bank, which issued its own report on the subject just last month, reckons that “45 million hectares’ worth of large scale farmland deals were announced” before the end of 2009), their varied motivations (from water-starved Gulf states looking to secure their food future in a post-oil world to Wall Street investors — including Warren Buffet — hedging against inflation), and the equally diverse responses they have provoked, with some commenters welcoming the investment as a new Green Revolution, and other labeling them as neocolonialist exploitation in development’s clothing.

But perhaps the most interesting possibility embedded within these land acquisitions is a wholescale renegotiation of the relationship between the urban and rural — between metropolitan regions and their agricultural hinterlands.

IMAGE: Starchy roots growing in Landgrab City.

Cities have always been just “the tip of an alimentary iceberg,” as Joseph Grima puts it, dependent originally on their immediate surroundings, and more recently, on a dynamic and largely invisible global network of interchangeable industrial farms, refrigerated warehouses, and cargo containers. Seen in this light, China’s purchase of arable acreage in Mozambique and the Sudan are a phase change — they solidify and stabilise a relationship that previously only existed as a transitory manifestation of capital’s ebb and flow.

Suddenly, Shenzhen’s ties to the farmland that supports it are more tangible than they have been in centuries — even though that land is hundreds of thousands of miles away.

IMAGE: Maize was the largest crop by area planted in Landgrab City.

The brilliance behind Landgrab City is to combine these parallel renegotiations — the shifting definition of the city and the evolving relationship between urbanised nations and their agricultural supply chain — and frame their convergence as a possibility.

“What if a city were to be no longer considered a geographically discrete entity, distinct from the landscapes of agricultural production it relies upon?” asks Grima. “What if spatial disbelief were to be suspended and a new definition of the city were to emerge as a consequence of the permanent bonds that are being forged: the city redefined as a discontinuous international – or even intercontinental – archipelago of urban and rural territories?”

IMAGE: Visiting Landgrab City.

Perhaps, suggests Grima, the landgrab phenomenon, by defining the geographical limits and economic importance of farmland, could actually provide the first step in forging a new relationship in which an increasingly urban world recognises its dependence on a vast agricultural hinterland and thus its own interest in protecting that land’s productivity and environmental health.

In the same way that today’s global cities, large enough to have meaningful influence but politically and culturally discrete enough to define a strong identity, are attempting to set terms on the geopolitical stage, could the transactional frame of land acquisition provide rural areas with the territorial unity, political visibility, and economic leverage they need to establish their own interests?

Clearly, we are currently a long way away from achieving this holistic vision. Grima is clear-eyed, describing the majority of the landgrab transactions thus far “as a unmistakably hierarchical system of exploitation.” Nonetheless, this is exactly the moment — when the default notion of a city and its supply networks are already in flux — to propose a more sustainable alternative.

IMAGE: Visiting Landgrab City.

In this context, Landgrab City is both more than a reminder of an invisible agricultural footprint and less than geopolitical manifesto. On its own, it does not attempt to propose how such a rural-urban partnership might work, politically, economically, or socially — but it does offer an inspiring call to anyone interested in cities and food to seize the moment and propose a better framework within which to negotiate that partnership.

[NOTE: If you’d like to add your thoughts on this issue to the Glass House Conversation (as well as in the comments here!), you only have a few hours left to do so: the Glass House comments close at 8:00 p.m. EST tonight, although they will continue to be available to read after that.]