Salt is essential. Globally, humans eat an average of 10 grams a day and we each contain roughly 250 grams, without which we would die.

IMAGE: Photograph courtesy Ryan Dewey.

As Mark Kurlansky explains in his book, Salt, the extraction of salt has inspired many of the world’s most ambitious public works projects, while the exchange of salt laid down many of the global trade routes still in use today.

As Kurlansky tells it, the Chinese developed an advanced system of urban plumbing inspired by their advances in salt-well bamboo pipework, the Romans built the first of their great roads, the Via Salaria, to bring salt into the interior of the Italian peninsula, and settlements all over the world—including Buffalo, New York—were situated at salt licks, to which convenient paths had already been blazed by animals (in that case, bison).

The salt at the end of the longest, most infrastructure-intensive supply chain in the world, however, is the salt from Improbable Oceans.

Artist and cognitive scientist Ryan Dewey is currently running a Kickstarter campaign to fund the production of what he describes as “the first true sea salt from oceans that don’t exist.” Its production process combines two elemental commodities that are shipped vast distances around the world only to be marketed based on their taste of place: mineral water and sea salt.

IMAGE: Photograph courtesy Ryan Dewey.

The result is small-batch, hand-harvested salt that captures the taste of two places that could never overlap outside the totalising geography of the grocery store—salt evaporated from the Wyoming-French ocean, for example, or the New Zealand-Icelandic sea.

The project began with kitty litter. Dewey is principal of the Geologic Cognition Society, a collective he founded in 2013 to attempt to make geologic timescales and forces more legible to humans. The minerals in the kitty litter on the shelves in an average Walmart may well, Dewey realised, have been mined in Wyoming, travelled by train to California, sailed to China to be processed, returned back to California by sea, and then traversed half way across the country again, via a central distribution center, to your store.

With an estimated 74 to 96 million total cats in America, and each indoor cat using, on average, 60 pounds of kitty litter each year, this distributed sedimentary movement is actually, it seemed to Dewey, “a pretty radical form of geo-engineering.”

IMAGE: Photograph courtesy Ryan Dewey.

At first, Dewey began assembling core samples of the mobile minerals available at your average supermarket: kitty litter, activated charcoal, pumice, and, of course, salt. The core samples were a tool, he explained, to help visualise “these imagined spaces that exist at the convergence of supply chains and retail inventory.” But, while he was scanning the shelves, he realised that, between the gourmet salt selection and the aisle of mineral waters, the grocery store was home to hundreds of latent oceans, each of which could yield an as-yet-untasted salt.

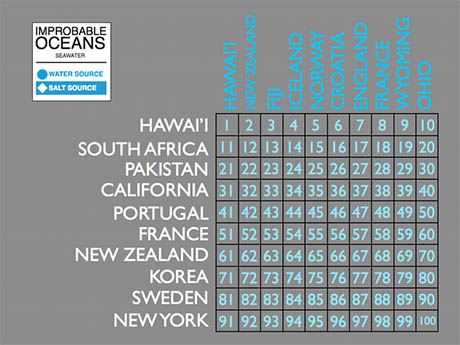

With no particular effort, Dewey was able to assemble ten mineral winters from across the globe—Hawaii, New Zealand, Fiji, Iceland, Norway, Croatia, England, France, Wyoming, and Ohio—and ten salts from equally far afield: Hawaii, South Africa, Pakistan, California, Portugal, France, New Zealand, South Korea, Sweden, and New York.

This immediately gave him the ability to make one hundred different improbable oceans in his Cleveland lab, in which the trace minerals that give Fiji water its particular flavour mingle with, for example, the unique “merroir” of Hawaiian sea salt. The result, after steam-condensing the ocean into a brine and then evaporating off the remaining water, is a seasoning whose taste perfectly captures the geography-distorting anyplace of the global supply chain.

IMAGE: Photograph courtesy Ryan Dewey.

Dewey’s early experiments have revealed that salt from an ocean made from French mineral water and Hawaiian salt tastes distinctly different from the salt that crystallises when he evaporates a combination of Hawaiian mineral water and French sea salt. (He prefers the former.)

IMAGE: Photograph courtesy Ryan Dewey.

The most improbable ocean, ranked purely on the mileage required to bring its two ingredients together in Dewey’s Cleveland base, is formed by the combination of New Zealand water with Portuguese salt. Foodies eager to taste these varying degrees of improbability themselves can choose to order single 2-dram vials of the New Zealand-Portuguese salt, inverse salt pairs, or entire flights.

The experience does not come cheap—Dewey thinks that his salt is almost undoubtedly the most expensive in the world, which is only fitting when you consider the resource-intensive supply chain that lies behind each improbable ocean (not to mention the time-consuming process of evaporating each micro-batch by hand).

Alongside the production process, Dewey plans to continue his exploration of how global supply chains shift geology, collapse geography, and create new kinds of places—as well as the products that express them.

He is experimenting with ageing his oceans, in order to reintroduce some kind of temporal variability into his salts. And he is planning to expand his harvest to include oysters: perhaps, he hopes, ending up with bivalves that have adapted over multiple generations to the particular waters of an improbable ocean.

Meanwhile, Dewey is also starting to cast salt in his furnace, and, with the Geologic Cognition Society, will be reconstructing the ancient brinescape that formed the rich seam of rock salt under Lake Erie for an exhibit opening in Cleveland in January. (A surprisingly large proportion of U.S. road salt comes from a Cargill-operated mine that extends four square miles out from the shore of downtown Cleveland, 1,700 feet beneath the lake’s surface.)

IMAGE: Photograph courtesy Ryan Dewey.

Visit Dewey’s Kickstarter page for your chance to taste the ineffable, improbable flavours of global trade and anthropogenic geo-engineering.

This is salt that can only exist at this particular moment in planetary history—salt that the ancient Chinese and Romans, for all their infrastructural ingenuity, could never have imagined. It combines the abstract logic of capital with the artisanal craft of micro-local production in seasoning form. Its ridiculousness is precisely the point.

I cannot wait to try it.