In 1900, the average dairy cow in America produced 424 gallons of milk each year. By 2000, that figure had more than quadrupled, to 2,116 gallons.

In this episode of Gastropod, we explore the incredible science that transformed the American cow into a milk machine—but we also uncover the disturbing history of prejudice and animal cruelty that accompanied it.

Along the way, we’ll introduce you to the insane logic of the Lifetime Cheese Merit algorithm and the surreal bull trials of the 1920s. This is the untold story behind that most wholesome and quotidian of beverages: milk. Prepare to be horrified and amazed in equal measure.

BREEDING A BETTER BULL

Something extremely bizarre took place in the early decades of the twentieth century, inspired by a confluence of trends. Scientists had recently developed a deeper understanding of genetics and inherited traits; at the same time, the very first eugenics policies were being enacted in the United States. And, as the population grew, the public wanted cheaper meat and milk. As a result, in the 1920s, the USDA encouraged rural communities around the U.S. to put bulls on the witness stand—to hold a legal trial, complete with lawyers and witnesses and a watching public—to determine whether the bull was fit to breed.

Livestock breeding was a normal part of American life at the dawn of the twentieth century, according to historian Gabriel Rosenberg. The U.S., he told Gastropod, was “still largely a rural and agricultural society,” and farm animals—and thus some more-or-less scientific forms of selective breeding—were ubiquitous in American life.

Meanwhile, the eugenics movement was on the rise. Founded by Charles Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton, eugenics held that the human race could improve itself by guided evolution—which meant that criminals, the mentally ill, and others of “inferior stock” should not be allowed to procreate and pass on their defective genes. America led the way, passing the first eugenic policies in the world. By the Second World War, twenty-nine states had passed legislation that empowered officials to forcibly sterilize “unfit” individuals.

A scrub sire, pictured in the USDA’s pamphlet, “From Scrubs to Quality Stock.” The caption reads: “There is seldom any uniformity in scrub stock. About the only things they have in common are 4 legs, 2 horns, a hide, and a tail.”

A “Better Sires: Better Stock” accredited dairy herd.

Combine the growing population, the desire for cheap meat and milk, and the increasing popularity of eugenics, and the result, Rosenberg said, was the “Better Sires: Better Stock” program, launched by the USDA in 1919. In an accompanying essay, “Harnessing Heredity to Improve the Nation’s Live Stock,” the USDA’s Bureau of Animal Industry proclaimed that, each year, “a round billion dollars is lost because heredity has been permitted to work with too little control.” The implication: humans needed to take control—and stop letting inferior or “scrub” bulls reproduce!

HEAR YE! HEAR YE! WELCOME TO THE COURT OF BOVINE JUSTICE

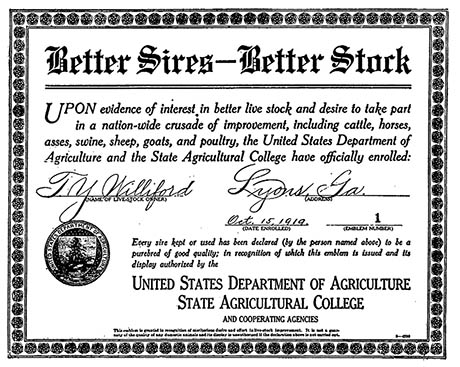

The “Better Sires: Better Stock” campaign included a variety of elements to encourage farmers to mate “purebred” rather than “scrub” or “degenerate” sires with their female animals. Anyone who pledged to only use purebred stock to expand their herd was awarded a handsome certificate. USDA field agents distributed pamphlets entitled “Runts and the Remedy” and “From Scrubs to Quality Stock,” packed with charts showing incremental increases of dollar value with each improved generation as well as testimonials from enrolled farmers.

The “Better Sires: Better Stock” certificate, awarded to farmers who pledged to use purebred rather than scrub bulls.

By far the most peculiar aspect of the campaign, however, came in 1924, when the USDA published its “Outline for Conducting a Scrub-Sire Trial.” This mimeographed pamphlet contained detailed instructions on how to hold a legal trial of a non-purebred bull, in order to publicly condemn it as unfit to reproduce.

The pamphlet calls for a cast of characters to include a judge, jury, attorneys, and witnesses for the prosecution and the defense, as well as a sheriff, who should “wear a large metal star and carry a gun,” and whose role, given the trial’s foregone conclusion, was “to have charge of the slaughter of the condemned scrub sire and to superintend the barbecue.”

The Order of Procedure, from the USDA’s “Outline for Conducting a Scrub-Sire Trial,” 1924.

In addition to an optional funeral oration for the scrub sire and detailed instructions regarding the barbecue or other refreshments (“bologna sandwiches, boiled wieners, or similar products related to bull meat” are recommended), the pamphlet also includes a script that begins with the immortal lines: “Hear ye! Hear ye! The honorable court of bovine justice of ___ County is now in session.”

The County’s case against the scrub bull is laid out: that he is a thief for consuming “valuable provender” while providing no value in return, that he is an “unworthy father,” and that his very existence is “detrimental to the progress and prosperity of the public at large.”

Several pages and roughly two hours later, the trial concludes with the following stage direction: “The bull is led away and a few moments later a shot is fired.”

The verdict (a foregone conclusion), from the USDA’s “Outline for Conducting a Scrub-Sire Trial,” 1924.

Within a month of publication, the USDA reported receiving more than 500 requests for its scrub-sire trial pamphlets. Across the country, the court of bovine justice was convened at county fairs, cattle auctions, and regional farmers’ association meetings, forming a popular and educational entertainment.

THE GENOMIC BULL

These bull trials may seem like a forgotten, bizarre, and ultimately amusing quirk of history, but, as Rosenberg reminded Gastropod, “they are talking about a lot more than just cattle genetics here.”

Indeed, the very same year—1924—that the USDA published its “Outline for Conducting a Scrub-Sire Trial,” the State of Virginia passed a Eugenical Sterilization Law. Immediately, Dr. Albert Sidney Priddy, Director of the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, filed a petition to sterilize Carrie Buck, an 18-year-old whom he claimed had a mental age of 9, and who had already given birth to a supposedly feeble-minded daughter (following a rape).

Buck’s case went all the way to the Supreme Court, with Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., upholding the decision in a 1927 ruling that concluded: “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” Historians estimate that more than 60,000 Americans were sterilized in the decades leading up to the Second World War, with many more persecuted under racist immigration laws and marriage restrictions.

Still from “When the Cows Come Home,” a USDA Extension film, c. 1935, extolling the benefits of livestock improvement. At one point, the voiceover intones: “Domestic animals are supposed to be the slaves of man, but the man who owns a low-producing, non-profitable herd has this idea reversed.” Via the Prelinger Archives.

Eugenics, with its philosophical kinship to Nazism, largely fell out of favor in the U.S. by World War II. But the ideas promoted in the bull trials—that humans can and should take increasing control of animal genetics in order to design the perfect milk machine—have gained ground throughout the past century, as breeding has become ever more technologically advanced.

As we discuss in this episode of Gastropod, the drive to improve dairy cattle through livestock breeding has led to huge innovations—in IVF, in genomics, and in big data analysis—as well as much more milk. But it has also continued, for better and for worse, to highlight the ethical problems that stem from this kind of techno-utopian approach to reproduction.

Listen now to find out more about the bull trials of the 1920s and meet the most valuable bull in the world, as we explore the history and the high-tech genomic science behind livestock breeding today. Along the way, we tease out its larger, thought-provoking, and frequently deeply troubling implications for animal welfare and society in general.