“Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

Or, “Consume a variety of nutrient-dense foods and beverages within and among the basic food groups while choosing foods that limit the intake of saturated and transfats, cholesterol, added sugars, salt, and alcohol.”

Or, “Don’t eat egg salad from a vending machine.”

IMAGE: “Don’t eat egg salad from a vending machine,” from Michael Pollan’s selection of New York Times‘ readers “Dietary Dos and Don’ts”

Whether you prefer to listen to Michael Pollan (In Defense of Food), the USDA (Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005), or the folk wisdom of New York Times reader David A. Wilson, there is certainly no shortage of public advice on what to eat.

“Deciding what to eat, indeed deciding what qualifies as food,” wrote Pollan in a recent article, “is not easy in such an environment.” His response, and the premise of his forth-coming book, Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual, is to collect and preserve cultural wisdom about food, as passed down through generations – both as a useful tool in itself, and as a counterbalance to the incomplete and frequently confusing conclusions of nutritional science.

IMAGES from Michael Pollan’s selection of New York Times‘ readers “Dietary Dos and Don’ts”

The guidelines Pollan has collected so far are well worth a quick browse: “If you are not hungry enough to eat an apple, then you are not hungry” (Emma Fogt), is a new personal favourite, while, “It’s better to pay the grocer than the doctor” (John Forti) has interesting implications in an era of agricultural subsidies and health-care reform.

Perhaps what is most interesting about Pollan’s proposition is the idea that nutritional advice has a cultural history – and that history is worthy of our attention. The Oxford-based nonprofit Social Issues Research Centre has begun assembling a timeline of dietary advice, which seems like a potentially infinite, as well as utterly fascinating, project – they welcome contributions by email to timeline (at) sirc.org. Hours can be lost there, exploring the wonders of walnut juice (heavily promoted by an Italian physician in 1689 as an elixir of long life) before moving on to read about the fashionable “horror of fat” inspired by Byron among his followers in the 1800s.

IMAGE: Still Life with Fruit Dish, Paul Cézanne, 1879-80, courtesy of MOMA. SIRC’s timeline describes widespread fruit phobias in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: “During the cholera epidemic of 1848, the Chicago Daily Journal spread a fear of orchard-grown produce. Still another report claimed that a man who simply passed a fruit stand filled with spoiled peaches suffered a severe attack of the ‘gripes.'”

Examining this timeline, it’s easy to see that any nostalgia for a historic and now-lost uncomplicated relationship with food is mistaken. Christians in AD 170 were worrying about whether eating fish was cannibalistic (because the fish might have fed on the bodies of drowned sailors), while as early as 1550 BC, ancient Egyptians were being advised to eat wheatgerm and okra to avoid diabetes.

While it’s possible to mine the shifting trends and sources of nutritional advice in search of lost nuggets of trustworthy advice, as Michael Pollan recommends, it’s potentially more interesting to look at the history of dietary recommendations in terms of much larger narratives to do with religion, science, social control, and even the construction of the self.

Looking at modern nutritional science in this context, we can trace the influence of historical beliefs and practices, as well as the limitations that contemporary models of food, bodies, and health impose on what we can see, measure, and understand. In other words, the echoes of early Christian enthusiasm for fasting and self-regulation and the nineteenth-century embrace of rational efficiency in feeding armies still both resonate today in the guilt associated with “bad” food choices, and the reductive logic of WeightWatchers’ “Points” system.

Similarly, ancient Greek systems of thought, including the idea that human health depended on balancing warm, cold, moist, and dry humours, naturally led to Galen‘s nutritional advice to restrict consumption of excessively dry foods in order to avoid “black bile.” How, then, do our contemporary medical beliefs and socio-cultural norms combine to exclude some nutritional possibilities, and reinforce others?

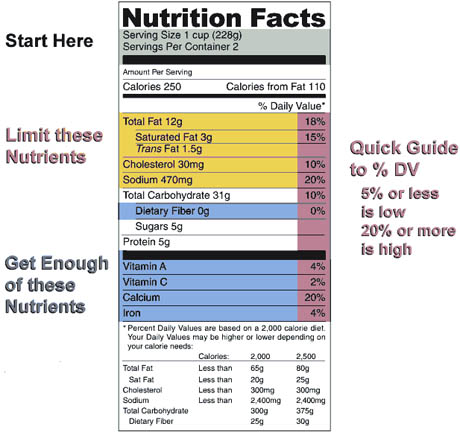

IMAGE: Basic advice on how to decode the information on a sample packaged macaroni and cheese mix nutrition label, courtesy of Clemson University. It’s worth considering that anything we don’t know really how to measure (e.g. probiotics) or value (e.g. potential pleasure or the energy used in producing the food) cannot be included in these labels, whose design nonetheless conveys a certain encyclopaedic completeness and transparency of information.

Australian scholar John Coveney, who explores the contemporary framework of food choices in his book Food, Morals, and Meaning, draws on the writings of French philosopher Michel Foucault (who, completely tangentially, looks like Michael Pollan’s long lost identical twin) to note that: “The combination of science and moral conduct – which in many ways forms the basis of governmentality – are never so apparent as in nutrition.”

By way of several more fascinating examples of dietary advice throughout history (including the nutritional calculations built into the first Australian minimum wage and Thomas Tryon’s dire warnings against the consumption of root vegetables by pregnant women), Coveney thus suggests that the confusing, contradictory haze of nutritional advice that Michael Pollan seeks to cut through is actually as much an expression of Western civilisation as liberal democracy.