The words “vanilla” and “chocolate” are used with equal frequency as both flavour and colour descriptors — but, curiously, the particular shades they describe have not always been the off-white and brown they signify today.

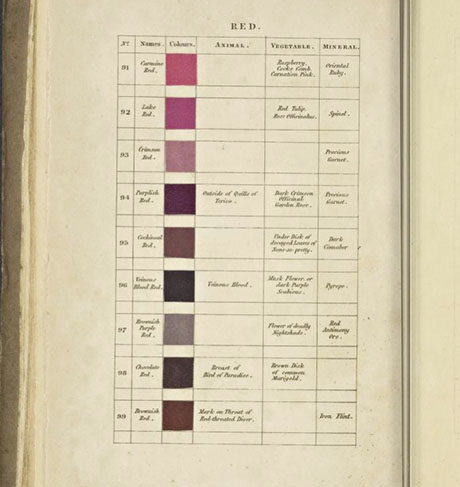

Instead, according to anthropologist Kathryn Sampeck, one of the earliest appearances of “chocolate”-colour, in Abraham Werner’s 1821 Nomenclature of Colours, is as a modifier for a particular shade of red. “Chocolate Red,” Werner writes, is “a veinous blood red mixed with a little brownish red.”

(At the risk of infinite recursion, “Brownish Red” is in turn defined as “chocolate red mixed with hyacinth red, and a little chesnut [sic] brown.”)

IMAGE: Chocolate red, as defined in Abraham Werner’s 1821 Nomenclature of Colours.

Meanwhile, vanilla pods are brownish-black, vanilla extract comes in shades of brown, and, when Europeans first encountered this new-world orchid in the sixteenth century, it was in the context of chocolate. Indeed, the Aztec name for the ground vanilla beans used as flavouring in their prized bitter, spicy, hot cacao-based beverage was “tlilxochitl,” derived from “tlilli,” meaning “black.”

What’s intriguing about vanilla’s dramatic colour shift, and chocolate’s more subtle one, is that they seem to coincide with a change in their respective consumption formats. When chocolate referred to a brown-tinted red, as opposed to straight-up brown, it was encountered primarily in powder and beverage form—and pulverised raw cacao is definitely on the lighter, rusty red end of the spectrum, even when diluted with water.

It wasn’t until 1828, seven years after Werner’s Nomenclature, that Dutch-process cocoa powder was invented, which is treated with alkaline salts to reduce cacao’s natural bitterness and acidity. Alkalisation, writes baking expert Alice Medrich, “darkens the color, making it appear to be more chocolatey.” The Dutch process also made the industrial scale consumption and production of chocolate possible for the first time, when Joseph Fry found a way to mix it with melted cacao butter and mould it into bars.

IMAGE: A colour comparison of powdered cacao versus dutch-processed cocoa, via.

Suddenly, chocolate moved from an aristocratic luxury—a frothy drink made from reddish powder—to an everyday treat, and one that was solidly brown. Funnily enough, at more or less the same time, writes Kathryn Sampeck, the rich, red-brown tones of “chocolate”-coloured fabrics went out of fashion in Britain, and brown dresses were relegated to Quaker widows and weavers.

Chocolate was cheap and brown, and its colour association shifted to match.

IMAGE: Vanilla beans, photographed by B. Navez.

Vanilla, on the other hand, was and still is expensive. Until 1841, when a twelve-year-old slave on the French-owned island of Réunion discovered how to hand-pollinate the vanilla orchid, its production was limited to the habitat of its natural pollinator, a small bee native to Veracruz, Mexico. Even today, vanilla is hand-pollinated, and, as a result, costs more than $100 per kilo, making it second only to saffron as the most expensive spice.

But how did it become associated with a creamy white?

Vanilla’s first recorded use as a colour name came much later than chocolate’s, in Aloys John Maerz and Morris Rea Paul’s A Dictionary of Color, published in 1930. Meanwhile, vanilla, used in reference to a culinary flavour, started showing up in European cookbooks in the seventeenth century, most commonly in recipes for drinking chocolate.

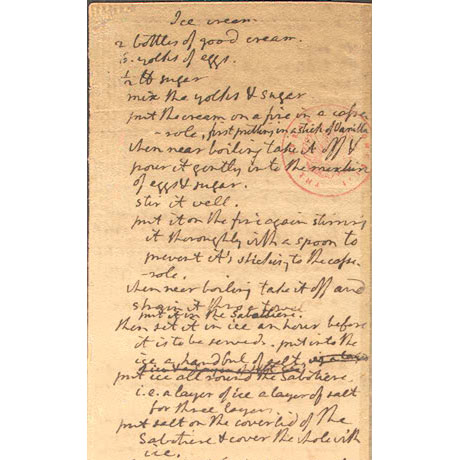

Its other early use is in ice cream — famously, Thomas Jefferson brought back a handwritten recipe for vanilla ice cream from Paris in the 1780s. But, in the days before mechanical refrigeration, ice cream was a rare treat, limited to the aristocrats who could afford to harvest and store natural ice or enjoyed outside the home.

IMAGE: Thomas Jefferson’s handwritten recipe for vanilla ice cream is a national treasure, housed at the Library of Congress.

Still, the prevailing theory is that because one of vanilla’s early usages was as a flavouring for ice cream, it became associated with the off-white colour of ice cream’s principal ingredient, cream.

What’s intriguing, however, is that that colour/flavour association did not become established until the early twentieth-century — well after the 1858 discovery and 1874 synthesis of artificial vanillin, which is the most signficant aroma molecule of the two-hundred-plus that make up natural vanilla flavour.

Vanillin, whether produced from petrochemicals, clove oil, or wood pulp, is a white to yellowish crystalline powder — and it costs a tenth of the price of real vanilla.

IMAGE: Vanillin powder, as offered by the Hangzhou Union Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

It is cheap, white to yellowish vanillin that made vanilla flavour so ubiquitous in America’s cakes, cookies, sodas, and ice creams: Slate reports that between 90 and 97 percent of all vanilla-flavoured products use synthetic vanillin, not real vanilla.

In other words, vanilla, in the artificial form that we most commonly encounter it, actually is off-white to begin with, ice cream or no ice cream.

This triumph of the petrochemical pretender reminds me of Sam Jacob’s fantastic appreciation of the avant-garde logic of blue raspberry, published last year, in Bompas & Parr’s Tutti Frutti. As a pioneer of the post-natural fruit spectrum, he suggests, blue raspberry breaks free of imitation, implying “that the things we eat might become abstract notions: the taste of wavelengths rather than biology.”

IMAGE: Raspberry-flavoured gummi rings.

In any case, as with chocolate, vanilla’s colour association reflects the most popular format in which we encounter the flavour — and thus is susceptible to cultural shifts over time.

What’s more, the colours associated with particular flavours are not just a historical or aesthetic curiosity. In the course of their fascinating research into multisensory integration, Oxford’s Crossmodal Research Lab have performed several studies showing that these kind colour/flavour preconceptions have a significant impact on our experience of food and drink.

For example, in one paper titled “Grape Expectations: The role of cognitive influences in color–flavor interactions,” Maya U. Shankar and her co-authors showed that British and Taiwanese test subjects, when presented with an identical brown drink, were “primed” to expect a different flavour experiences based on pre-existing associations: the British consumers expected a sweet “cola” flavour, while the Taiwanese associated that shade of brown with a popular grape drink instead, and were anticipating more of a tart, fruit flavour. And these kind of colour-associated flavour cues exert a significant impact on actual flavour experience: one often-cited study found that nearly half of its participants reported that an orange-coloured, cherry-flavoured drink tasted of orange.

IMAGE: Vanilla, as defined by the Pantone colour system.

The colour of flavour, it seems, offers both historical insight and future-shaping potential. It not only tells us something about the format in which that flavour was first consumed, but also determines our future food and drink expectations, and thus experiences.

In this context, it’s hard not to mourn the loss of chocolate and vanilla’s original hues. I can’t help but imagine that a reddish chocolate might actually seem more spicy and luxurious than a brown one, and that re-inventing vanilla as an exotic black orchid could put an end to its use a synonym for bland.