Earlier this year, Geoff Manaugh of BLDGBLOG and I launched a new project, Venue, in partnership with the Nevada Museum of Art’s Center for Art + Environment and Studio-X NYC, and with the generous support of the Western States Arts Federation (WESTAF), Nevada Arts Council, and the National Endowment for the Arts. The story below is cross-posted from the Venue site, where you can also read about abandoned silver mines, oilscapes, petroglyphs, and more.

According to Jack Chambers, proprietor of the Sonoma Valley Worm Farm and a former Delta Air Lines pilot, when he got in the cockpit of a 747, “the other guys would have second homes and boats and be into golf. But I was the worm guy.”

IMAGE: Jack holding some of his worms. All photographs by Nicola Twilley.

Venue visited Chambers on a sunny September afternoon, and, as he showed us around the farm, he explained that his worm obsession began, straightforwardly enough, as a gardening hobby. A friend told him about a local farmer who had earthworms for sale, and so, twenty years ago, in 1992, Chambers paid a visit to Earl Schmidt, a former mink rancher, enthusiastic angler, and bait worm farmer.

Five days and one 5 gallon bucket of Red Wigglers (Eisenia fetida) later, Chambers’ home compost pile was a rich, deep black color with a crumbly texture that he’d never been able to achieve before. He started hanging out with Earl, helping out in return for a chance to learn about worms.

IMAGE: Worm Farm sign.

As they picked worms side-by-side over the next three months, Earl told Chambers that he was looking forward to retirement and finally having the time to fish. Chambers, “without really knowing what I was getting into,” found himself offering to buy the place.

A crash course in all things worm quickly followed, including a carefully scheduled layover in Vigo, Spain, to attend the World Worm Conference, and conversations with vermiculture pioneer and Ohio State University professor, Clive Edwards. Trial and error also played a role, with Chambers reminiscing about the “worm volcano” he accidentally created by experimenting with cornmeal as a feed — 50,000 disgusted worms all crawled over the sides of the bin at once, in a scene worthy of a horror movie. “Now, if I’m trying something new,” explained Chambers, “I only add it to quarter of the bin, to leave room for escape.”

Chambers credits his pilot’s appreciation for standard operating procedures and checklists for many of the technical improvements he’s introduced over the past twenty years. For example, in order to pre-compost the manure source and kill any pathogens or weed seeds before feeding it to the worms, Chambers arrived at his own design for a three-bin forced-air system, complete with a rigorously optimized schedule of turning, blowing, and releasing gases. “If I’ve done anything with worms,” he says, “it’s that.”

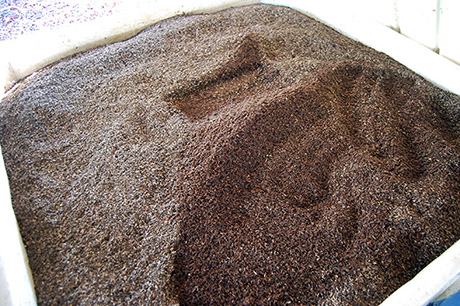

IMAGE: The compost is kept at 130 degrees for several days to kill pathogens and weed seeds.

That is certainly not all, though. As we moved under the corrugated steel sheds that house the farm’s four million worms, Chambers explained that he realized early on that, in fact, “the vermicompost is the big deal, not the worms.” In other words, rather than simply feeding worms in order to harvest them for sale to sport fishermen and gardeners, Chambers focused on marketing their castings, particularly to the region’s high-end grape-growers.

To do so, he has built four ninety-foot long continuous flow vermicomposting bins, based on an original blueprint by Clive Edwards, but improved over the years to the point that he now has a patent pending on the design.

IMAGE: The VermiComposter CF40.

“This is high-tech for worms,” explained Chambers, as he demonstrated his most recent iteration, the VermiComposter CF40. In sixty days, pre-composted manure will make its way from top to bottom of the four-foot deep bins through a continuous conveyor-belt system of worm digestion.

The raised bins are fed from the top twice per week, and harvested from the bottom once weekly using an automatic breaker bar. A wire mesh tumbler then separates the worms from their excretions; the worms go back in the bins and the remaining black gold is sold for a dollar a pound.

IMAGE: Harvesting with the VermiComposter.

Earthworms are easy to overlook, but among those who do observe their work, they seem to inspire extreme devotion, counting among their historical fans both Aristotle and Charles Darwin. Chambers is equally enthusiastic. As we dug our hands into the warm, soft compost and watched the worms we had disturbed wriggle back into the darkness, he expounded on the mysteries of worm reproduction as well as numerous studies that have shown vermicompost’s beneficial impact on germination rates, disease suppression, flavor, and even yield (up to a twenty percent increase for radishes, according to Clive Edwards’ colleagues at Ohio State).

IMAGE: Jack explains how to make compost tea.

Vermicompost is typically used as a potting medium — Chambers’ advice is to “put one cup in the hole with your seed or transplant” — or it can be brewed at 73 degrees for 24 hours to make a “compost tea” that can be sprayed onto the soil or plant directly. Although it is between four and fourteen times more expensive than regular compost, Chambers argues that, like a high-end skin product, vermicompost’s benefits and economy of use make it well worthwhile:

I tell vineyards to think of it like insurance. After all, a vine costs about $3, and some vineyards lose as many as twenty percent of their new plantings. With our vermicompost, they usually lose less than one percent.

IMAGE: The Sonoma Valley Worm Farm has a few acres of Syrah, as well as a lush kitchen garden.

Chambers and his wife even planted four hundred vines of their own, losing only two, and they attribute their ongoing victory over powdery mildew to regular applications of compost tea. They make a very good “Worm Farm Red,” that we were lucky enough to sample and that even won a gold medal in the amateur category at the 2008 Valley of the Moon Vintage Festival.

Sonoma Valley Worm Farm already makes more than 200,000 lbs of vermicompost a year, but Chambers took early retirement from Delta last year, and has big plans for the business. The day we visited, he had just finalized the agreements for a new facility that will more than double his capacity, as well as incorporate several new improvements to his existing equipment.

IMAGE: Jack talks us through the architectural plans pinned up in his office.

As we examined the architectural plans in Google SketchUp, Chambers described his vision for the next generation VermiComposter CF 40, which will include electronic moisture and temperature monitoring and automated feeding.

While he waits for the new facility to be built, he’s already experimenting with feeding the worms an extra inch of compost per week, to see whether he can increase their productivity. Meanwhile, in response to interest from California’s berry giant, Driscoll’s, he’s started working with compost tea-kettle manufacturers on a unit that could brew up to 250,000 gallons at a time. In fact, Chambers’ only concern as he scales up, he told us, was what he would do when the worms’ demand outstripped the manure supply of the organic dairy farm (Straus Family Creamery) that he currently works with.

IMAGE: The finished product, ready to ship.

Given that, last year, the EPA estimated that thirty percent of annual landfill contents could have been recycled through composting, and that California’s dairy cows produce 30 million tons of manure annually, much of which is stored in waste lagoons where it risks contaminating groundwater, it seems as though feeding four or five million new worms is not going to be much of a challenge at all. The fact that those worms will not only remove that waste from the environment, but also transform it into something that scientists are calling “pretty amazing stuff,” as well as “the next frontier in biocontrol,” is even better.

Chambers told us that he is convinced that “worms are going to be the next big thing in agriculture.” If we’re smart, it will be.