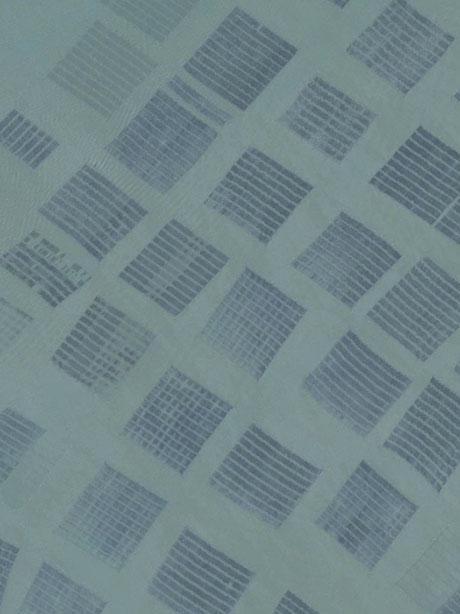

IMAGE: Seaweed farming rafts off the coast of the Chinese province of Jiangsu, south of the city of Qingdao, Bing Maps, via Mammoth.

Via Mammoth’s Rob Holmes, we learn that the coastal city of Qingdao, China, is experiencing what local officials, channeling Don De Lillo, have called “a large-scale algae disaster.”

According to The New York Times, “an area larger than Connecticut had been affected by the mat of ‘sea lettuce,’ as it is known in Chinese, which is generally harmless to humans but chokes off marine life and invariably chases away tourists as it begins to rot.”

Although different theories abound, some biologists blame the sea-lettuce bloom on the expansion of seaweed farming further along the coast. China is the world’s largest producer of edible seaweeds, and Qingdao’s neighboring province of Jiangsu experienced a boom in nori production following a 2005 World Trade Organisation ruling forcing Japan to open its markets to Chinese products.

IMAGE: The mass culture of porphyra or nori. Oyster shells strung together and hung from rails in a Japanese culture tank (top left), a Prefectorial Seedling Centre in Japan (top right), shallow shell culture tanks in China (bottom left), clam shells laid flat in a Chinese culture tank (bottom right). From The Seaweed Site and Porphyra: Harvesting Gold from the Sea, by Ira Alan Levine and Dinabandhu Sahoo.

As a side note, industrial nori cultivation is an extraordinary process. The seaweed releases “conchospores” in the spring, which are cultured in empty oyster or clam shells that have either been hung vertically or spread out across the bottom of the tank. Roughly five months later, in the autumn, the baby seaweed plants are seeded onto square nets, most often by rotating a drum of synthetic fibre mesh through the tanks. The nets are then attached to plastic tubing frames to make rafts of up to 400 seaweed “tiles,” which can be staked out in shallow water or attached to styrofoam floats, as in the satellite image at the top of the post.

IMAGE: Mesh drums with about thirty nets wound round them are seeded with Porphyra/nori by being dipped in the culture tanks. Photograph via The Seaweed Site.

IMAGE: Porphyra aquaculture structures used closer to shore in the Jiangu coastal region (left). Green Ulva prolifera fronds growing on the raft support structures are scraped off by the growers, drift out to sea, and develop into massive macroalgal mats. Photographs from “The world’s largest macroalgal bloom in the Yellow Sea, China: Formation and implications,” Dongyan Liu, John K. Keesing, Peimin He, Zongling Wang, Yajun Shi, and Yujue Wang.

The aquatic cousin of a combine harvesters are used to gather the mature crop at the end of its 40-50 day growing period. It is then washed, dried, and processed, in a mill that resembles a paper-making machine, into the thin rectangular flakes that wrap our sushi rolls.

In Jiangsu, as nori production more than tripled in scale since 2005 to cover 38,260 hectares by 2010, seaweed rafts have moved farther and farther offshore, and now stretch up thirteen kilometres out to sea. That, say the scientists behind a recent paper, means that the Ulva prolifera algae released when the rafts are cleaned are picked up by different currents, dragging them out to sea where conditions are perfect to turn “small patches of macroalgae into the world’s largest green tide.”

IMAGE: Swimming in the green tide. Photograph from the South China Morning Post.

The stakes are high on both sides: Seaweed farming is a 488 million dollar industry in Jiangsu, while clean-up alone costs Qingdao $30 million, with up to $100 million in abalone and sea cucumber farm damages, and lost tourism revenue on top of that. While one of the paper’s contributors, John Keesing, spoke to The New York Times, the study’s lead author, Liu Dongyan, declined to talk to the South China Morning Post, “describing the finding as too sensitive as it involved ‘different departments.'”

Meanwhile, local officials in Qingdao have mustered a fleet of boats, nets, bulldozers, and trucks to collect as much as 160 tons of algae a day, which, according to the Los Angeles Times, is taken to one of “five processing depots, where the water is extracted and the material is dried, then processed into animal feed, fertilizer or a medicinal supplement known as hutai sugar, which is said to help lower blood sugar.” Locals have apparently also shared ingenious recipes to make use of the algal invasion, including one for “a dish that resembled guacamole.”

IMAGE: Nori cultivation in Fujian, China. Photograph by Wong Chi Keung, via People and Planet.

This, as Holmes eloquently puts it, “is feedback, the accumulated white noise of aquaculture.”