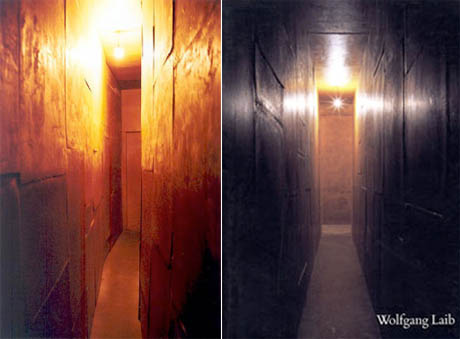

IMAGE: Detail from Penelope Stewart’s Apian Screen, via Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre. Photo courtesy of the artist.

In a tiny room off the main gallery space in Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre, Canadian artist Penelope Stewart has glued hundreds of beeswax tiles to the walls, entirely covering the space from floor to ceiling. The tiles are four-inch squares, each a slightly different shade of golden brown, and they envelop the small space with a subdued but luminous warmth and an intense smell of honey.

IMAGE: Parois, by Penelope Stewart. Photo courtesy of the artist.

This is not the world’s first beeswax chamber – Stewart’s earlier works include a stunning 2007 piece, Parois, which used 4000 beeswax tiles to cover the walls of a small room in the Musée Barthète, Boussan, France. That installation drew its inspiration from the museum’s amazing collection of tiles, which ranges from ancient fragments to Tunisien ceramic and French faïence.

IMAGE: Tiles on display at the obscure but fascinating Musée Barthète.

IMAGE: Detail from Penelope Stewart’s beeswax chamber at the Musée Barthète, inspired by the permanent collection. Photo courtesy of the artist.

IMAGE: Penelope Stewart’s beeswax chamber at the Musée Barthète at night. Photo courtesy of the artist.

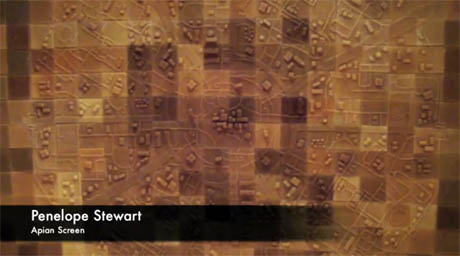

The Museum De Pont in the Netherlands also has its own beeswax cabinet: in 1992, the German artist Wolfgang Laib used slabs of beeswax to construct a narrow, dead-ended space lit by a single light bulb, called Wachsraum.

IMAGE: Wolfgang Laib’s beeswax chambers: on the left is his 1992 Wachsraum at the Museum De Pont, and on the right is the cover of Wolfgang Laib – A Scented Journey, a booklet documenting the construction of a beeswax space in 1994, at the Henry Moore Foundation Studio in Halifax.

Even when experienced only through photos, these spaces feel sensorially overwhelming: the combination of warm, variegated yellowish light with the waxy, crystalline, yet invitingly malleable surface texture, as well as the reported sweet honey scent, seems both compelling and slightly headache-inducing. According to Kamiel van Kreij, whose graduate thesis at the University of Delft focused on sensory amplification in architecture, the wax also acts as an acoustic dampener, increasing the space’s visceral intensity.

Judging from the popularity of pieces like Anthony Gormley’s Blind Light or Olafur Eliasson’s Weather Project, I’m not alone in my enthusiasm for immersive installations of this sort. Something about the disorientation and re-engagement of underused senses they induce is incredibly refreshing; no Googleplex, university library, or writers’ colony should be without its own beeswax chamber or halogen-lit salt cave.

In any case, what’s especially interesting about Stewart’s most recent beeswax room, Apian Screen, is that the designs on the tiles are drawn from utopian urban plans. According to a video interview, Stewart started looking at modernist drawings and proposals for the ideal metropolis after a visit to Canberra, the Australian capital city designed from scratch by Walter Burley Griffin at the start of the twentieth century.

IMAGE: Penelope Stewart’s Apian Screen, as seen in this video interview.

Fairly early on in her research, Stewart was struck by the frequent use of honeycomb and beehive metaphors in the imaginary cities of Gaudi, Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier. In fact, entire books have been written on the influence of the “lucid, modular structure” of the apiary on the Modern movement; apparently, Le Corbusier “read The Dancing Bees by scientist Karl von Frisch several times, making extensive notes in the margin.”

IMAGE: Penelope Stewart in front of her Apian Screen, as seen in this video interview.

Stewart’s next step was to tessellate the abstract forms of ideal cities, both built and unbuilt. The final installation remixes elements of Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasília, Walter Burley Griffin’s Canberra, Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City, among others.

It’s an almost-too-perfect match of material realisation and metaphor: the organic nature of the vari-coloured beeswax both recalls and betrays its Utopian hive associations; the aesthetically pleasing recombination of the tiled squares plays on the modernist preference for geometric forms, repeated in alignment; while the enclosed, warm, and sensorially rich space of Stewart’s room is in sharp contrast to the hygienic efficiency and imposing open spaces of the twentieth-century planned city. Indeed, the Toronto Star‘s reviewer notes that Apian Screen “is such a tight little package, aesthetically and conceptually, that I felt a little giddy.”

Exactly.

NOTE: I learned of Stewart’s Apian Screen from Quiet Babylon‘s Tim Maly. His reliably interesting Twitter feed is @doingitwrong. Thanks, Tim! Unfortunately, Apian Screen closed just yesterday – we can but hope it will travel.