IMAGE: Cadbury’s Dairy Milk chocolate bar vs. Hershey’s Milk Chocolate bar.

When iconic American chocolate-makers Hershey announced an (ultimately unsuccessful) bid to take over the equally iconic British confectionery company, Cadbury, most discussion revolved around one of two things: business reporters focused on the stock price implications of any deal, while the food media conducted taste tests, and were joined by patriotic British journalists in their anxiety that Hershey might meddle with Cadbury’s infinitely superior formula.

IMAGE: Cadbury promotional booklet cover, circa 1925. From the collection of Mike Ashworth, scanned from Fire and Knives.

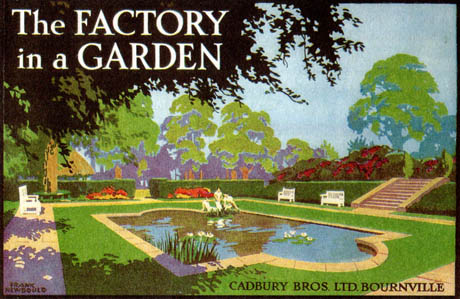

Until I received my copy of the second issue of a new British food quarterly, Fire and Knives, however, I had not considered the urban planning implications of a potential Hershey/Cadbury merger. In a short article, food writer Douglas Blyde pays a visit to Bournville, the purpose-built model town built and owned by Cadbury to house its factory and employees:

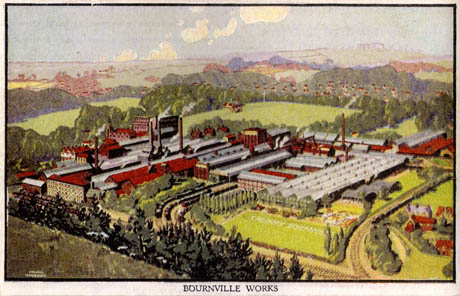

In 1879, aged 40, George [Cadbury] opened the “factory in a garden”—the exotically-named Bournville, with a factory and twenty-four cottages built by the Bourn brook on Birmingham’s greenfield outskirts. His stated goal was of “alleviating the evils which arise from the insanitary and insufficient housing accommodation supplied to large numbers of the working classes, and of securing to workers in factories some of the advantages of outdoor village life, with opportunities for the natural and healthful occupation of cultivating the soil.

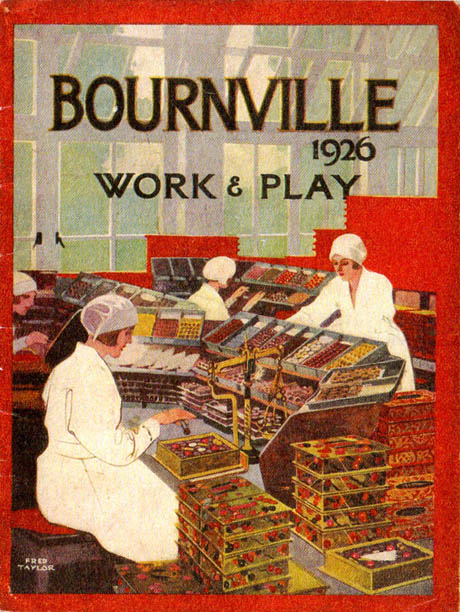

IMAGE: “Bournville 1926 – Work and Play” promotional booklet cover. From the collection of Mike Ashworth, scanned from Fire and Knives.

Nearly a quarter of a century later, in 1903, Milton S. Hershey broke ground on his new chocolate factory and model town in central Pennsylvania named, more predictably, Hershey. Hershey’s declared aims are only available second-hand, since he was all but illiterate, but a contemporary article in the Harrisburg Independent reported that the new town was to be “patterned after those in England,” while in a June 1903 piece in The Business World, journalist Joseph Solomon rapsodises:

We shall soon see the actuality of his intention … improved conditions which work to the good, socially, physically and morally, of all concerned … There is no provision for a police department, nor for a jail. Here there will be no unhappiness, then why any crime?

IMAGE: (left) Chocolate Avenue, Hershey’s main street, in the 1920s; (right) Homes along Cocoa Avenue in the 1920s. Both images from One Man’s Vision: Hershey, A Model Town (pdf).

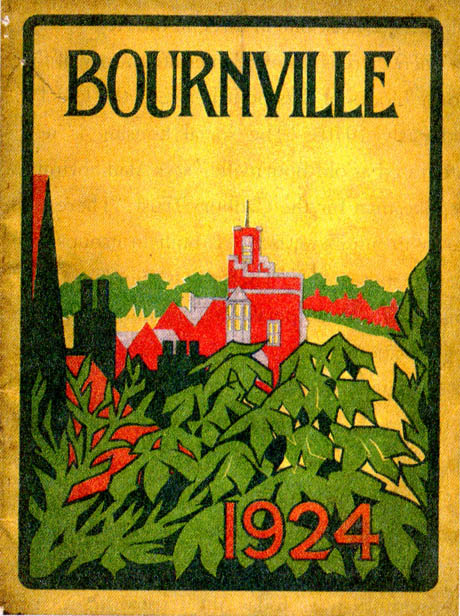

A little more research (in Tim Richardson’s history, Sweets) reveals that a penchant for town planning and urban improvement was a traditional eccentricity of chocolate manufacturers. In England, Rowntree’s (makers of Kit Kats, Smarties, and Aero bars) also built their own model village—New Earswick, near York—in 1902. Meanwhile, in continental Europe, “Papa Suchard” “slowly expanded the ‘Cité Suchard,’ with houses for workers, some buildings with minarets (reflecting Suchard’s fixation with the East) and even an alcohol-free restaurant called ‘Tempérance'” from the 1860s.

IMAGE: “Bournville 1924” promotional booklet cover. From the collection of Mike Ashworth, scanned from Fire and Knives.

Richardson continues with the lesser examples of amenity-bestowing chocolate-manufacturers: Menier (“houses, school, a bank, and a library for workers from the 1870s”), Sprüngli (“a park, complete with serpentine walks, a fountain, and arbour”), and Tobler (houses for workers, as well as “an Alpine holiday retreat”). In fact, of the early confectionery moguls, only Forrest Mars stands out for his lack of architectural ambition.

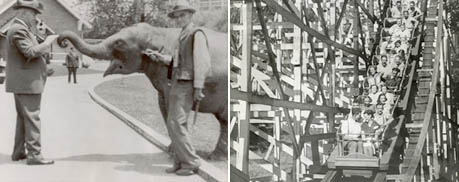

Bournville and Hershey are clear front-runners, however, in the utopian scope of their urban designs. “Keen sportsmen,” reports Douglas Blyde, George and Richard Cadbury built “a bowling green, squash courts, a cricket pitch, courts for hockey and tennis, a running track, a fishing lake, and swimming pools.” Meanwhile, Milton Hershey’s plans included a standard-issue model town park from the beginning, and rapidly grew to include a “men’s club, a gymnasium and pool, a library, bowling alley, and public meeting rooms.” By 1923, Hershey had added a rollercoaster, which then expanded into a full-blown theme park, complete with zoo, big top, and waterslides.

IMAGE: Rollercoaster and elephant at Hershey Park, from the website of Hershey, PA: The Sweetest Place on Earth™

The towns that chocolate built are a curious blend of idealistic vision and pragmatic company town—the convergence of paternalistic benevolence and capitalist expedience. The Cadbury and Rowntree brothers were devout Quakers, whose humanitarian beliefs undoubtedly impelled them to improve the living conditions of their workers. Hershey’s benevolence seems not to have been motivated by religious belief, despite the fact that he was raised by a strict Mennonite mother. However, he was undoubtedly a grand philanthropist, anonymously giving away his entire personal fortune (an estimated value of $60 million in 1918) at the age of sixty-one to endow a school for poor and orphan boys.

Nonetheless, as Tim Richardson is quick to point out, “philanthropy was always accompanied by efficiency in these developments.” Hershey chose his rural location, for example, less from a desire to ensure his factory workers had access to healthy, rural air, than for strategic gain—deep in dairy-farming land to ensure a cheap supply of milk, but close enough to major cities (Philadelphia and New York) to allow cost-efficient distribution.

IMAGE: (left) Celebrating the birth of lion cubs at Hershey Park Zoo; (right) Waterslides at Hershey Park, both in the 1930s. Both images from One Man’s Vision: Hershey, A Model Town (pdf).

Similarly, Richardson notes that the Cadbury brothers also believed that improving the welfare of their staff would led, ultimately, to a more profitable business. The expansive front and back gardens of Bournville workers’ houses were laid out in accordance with George Cadbury’s principle that “no man ought to be condemned to live in a place where a rose cannot grow”—but in fact, reports Blyde, they were more pragmatically “stocked with apple, pear and plum trees, and gooseberry bushes to help promote fruit and vegetables over meat.”

IMAGE: “Bournville Works,” postcard c.1930. From the collection of Mike Ashworth, scanned from Fire and Knives.

This form of enlightened self-interest follows an earlier successful template: the profitable cotton mills and company town of New Lanark, created by utopian socialist Robert Owen. Indeed, several eighteenth-century industrialists shared the Cadburys’ and Rowntrees’ belief that a healthy, happy workforce would drive profits. Not all of them, however, went to the trouble of building a proprietary model town to demonstrate and enforce their convictions. In fact, according to Gillan Darley, author of Villages of Vision, company towns were traditionally the preserve of eccentric outsiders or extractive industries, such as coal-mining or lumber companies that required their workers to live in remote, unappealing locations.

So why did so many chocolate-makers build their own company towns? In part, it is because the great nineteenth-century chocolate magnates were outsiders: their Nonconformist religious beliefs made it difficult or impossible for Quakers like Joseph Rowntree, Joseph Fry, or George and Richard Cadbury to attend university, join the military, or pursue other establishment careers. Meanwhile, chocolate held a special attraction for teetotal Quakers and dissenters: hot cocoa, in particular, was “identified as a possible corrective to the social ruin caused by alcohol,” acccording to Blyde. Both Hershey and Bournville were regulated as “dry” towns—Bournville apparently still has no pub or off-licence to this day.

IMAGE: New Earswick (“Kit-Kat-ville”) and Hershey today. Left image via; right image via.

In addition to the high proportion of reform-minded outsiders in the chocolate business, Tim Richardson suggests another reason for the prevalence of chocolate company towns:

More than in other industries, it was in the management’s interests to keep their workers relatively content, because confectionery manufacture is an extremely hands-on operation, and the finished article, though mass-produced, is supposed to be a luxury comestible.

In other words, model towns like Bournville, New Earswick, Cité Suchard, and Hershey are a direct result of the artisanal elements of the industrial chocolate-making process, combined with the predisposition of idealistic nonconformists to seek their fortunes in cocoa. They are the historical, cultural, and technical aspects of chocolate, poured into an urban mould.

IMAGE: Historic maps of Bournville (left) and Hershey (right).

IMAGE: Cover of 49 Cities, by architects Work AC.

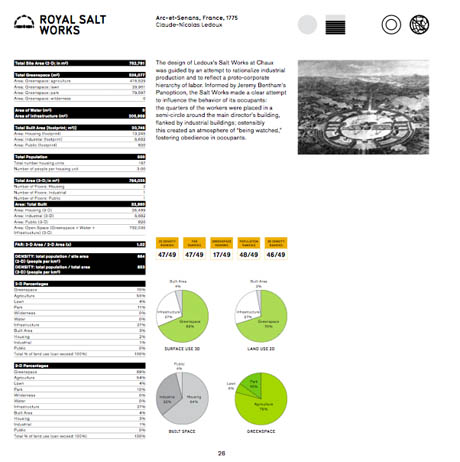

It’s exciting to image a 49 Cities-style analysis of the architectural embodiment of chocolate—just as Work AC subjected forty-nine utopian city plans from throughout history to a rigorous quantitative analysis, why not examine Bournville, Hershey, and the rest side-by-side? Are there formal similarities or an ideal chocolate town density? Which city leads in terms of amenities and green space? What proportion of built space is public versus residential in chocolate utopia?

In short, what does chocolate look like in terms of urban design?

IMAGE: The planned development of the Royal Salt Works by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, as analysed by Work AC in 49 Cities.

Residents of chocolate towns were also expected to live according to unique behavioural codes: for boys in the Hershey school, hand-milking cows every morning was compulsory until 1990, while the original Bournvillians were expected to adhere the Cadbury brothers’ “Suggested Rules of Health,” which included: “wearing roomy boots and loose but warm clothing (with daytime clothing not to be worn at night), sleeping eight hours a night in single beds, and conducting family worship every day.” Blyde adds that,

Modern Bournville is also webbed in well-intentioned regulation, covering hedge height, door- and window-frame colour, with bans enforced on visible satellite dishes, parked caravans, paved front gardens, takeaway restaurants, and uPVC windows.

IMAGE: (top left) Bournville today; (top right) Russell Cooper and his partner Barbara Pyatt, proprietors of Russell’s Butchers. Cooper told the BBC, “The Bournville Village Trust ensures everything is looked after properly – even the organising of hanging baskets.” Both images via the BBC.; (bottom) Over 30s Disco in Bournville, photo by Douglas Blyde.

On that note, I’m reminded of Michael Sorkin’s Local Code, in which the architect proposes template code for an ideal model city at latitude 42ºN. Could an equivalent set of rules for the ideal chocolate town be extrapolated from Hershey and Bournville’s experiments? What zoning laws and building standards guarantee superior chocolate production? Should Green & Black’s start lobbying for Lecco, Italy, (the site of its largest factory) to adopt model chocolate town code? And if you applied it to a rust-belt city of today, could you entice a chocolate corporation to set up shop?

IMAGE: (left) Max Geernaert, Bournville resident: “I live with my mum and am due to move out of the area at the end of the year. But I think my mum is settled here for life.”; (right) Barbara Adams, Cadbury pensioner: “Although I retired 20 years ago I still come back for various dinners and events that Cadbury organise. I do love it here, I think it’s very pretty. But there isn’t a big enough shopping centre for me.” Both images and quotes via the BBC.

Today, Bournville has a reputation as “one of the nicest places to live” in the U.K., although opinion is divided as to whether that is due to its demographic and experiential homogeneity, rather than a product of visionary town planning. (An interesting aside: according to an article in The Telegraph, former Beirut hostage John McCarthy, “visited the village while making a film about the meaning of home and couldn’t stand it. He said it would drive him crazy having to live somewhere so quiet and orderly.”) Somewhat surreally, Poundbury, Prince Charles’ experiment in town planning, claims to have learned from Bournville, and indeed, now boasts its own chocolate factory.

IMAGE: (left, via) House of Dorchester chocolate factory, Poundbury; (right, via) HRH himself, visiting the chocolate factory.

As today’s urban planners increasingly seek to reintegrate high-value, artisanal manufacturing into today’s service-industry cities, perhaps there are lessons to be learned from the chocolate towns of the past. In any case, chocolate’s architectural expression merits further study, as a lens through which to understand its cultural history.