At the recent Thrilling Wonder Stories all-day speculate-athon, Geoff Manaugh and I ended up speaking as part of the “Counterfeit Archaeology” panel, alongside designers Dunne & Raby. To explore this concept of creating alternative artifacts and inventing potential pasts in order to understand the present and tell stories about about the future, we talked about animal printheads, rats, nuclear waste entombment sites, and more.

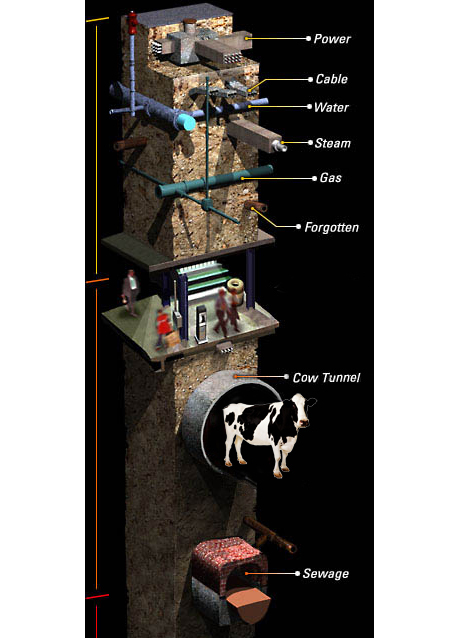

IMAGE: Subterranean New York City, my altered version of a diagram by National Geographic.

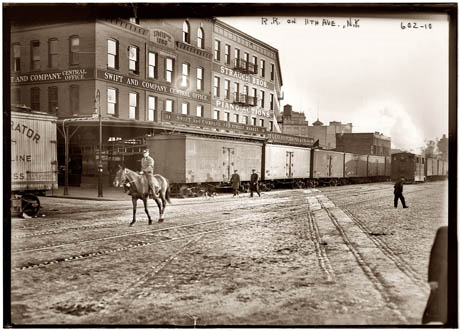

As part of our presentation, I revisited the mythical cow tunnel(s) of New York. This structure (or these structures, depending on whose version of the story you listen to) was supposedly built at the end of the nineteenth century, as an infrastructural response to the cow-jams that blocked streets in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan. (The increased quantity of cattle arriving in the city was due, in part, to another infrastructural innovation: the railway.)

In any case, its/their very existence is shrouded in uncertainty: cattle tunnels have been rumoured to exist beneath Twelfth Avenue at both 34th Street and 38th Street, but also somewhere on Greenwich, Renwick, or Harrison Street near the present-day entrance to the Holland Tunnel, and even as far afield as Gansevoort Street in the West Village. According to second-hand reports collated by utilities engineer turned self-published mystery writer Brian Wiprud, the tunnel is, variously: oak-vaulted; lined with fieldstones; built of steel; demolished to make way for a gas main; or perfectly preserved.

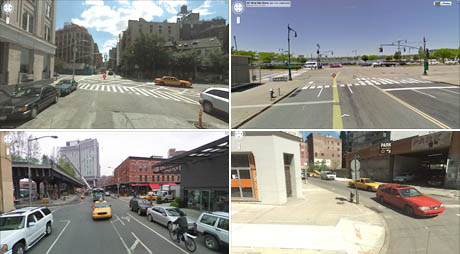

IMAGE: Google Street View shots of the surface above some of the reported cow tunnel locations.

A guy from the telephone company even claimed to have met someone whose boss said he had rescued a musket from the entrance to one. Not to be outdone, in 2004, the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation apparently declared that “if intact,” the cow tunnel(s) would indeed be eligible for landmark status.

What’s amazing about these elusive cow tunnels is that, whether or not they actually exist (in fact, especially if they don’t), they form a shared urban fantasy — a mythical meat-processing infrastructure haunting contemporary New York City.

In a world where our steak frequently arrives in a polystyrene tray, sitting on a nappy in a modified-atmosphere bubble, the cow tunnels could be analysed as the city’s agricultural unconscious, returning in the form of rumour and legend. Their longevity and recurrence, in spite of the lack of any physical corroboration, suggests that they form a powerful thread in the urban imaginary — and a ready-made narrative to be exploited by locavore designers.

IMAGE: A cowboy on 13th Street and Eleventh Avenue in the Meatpacking District, NYC, 1911, via.

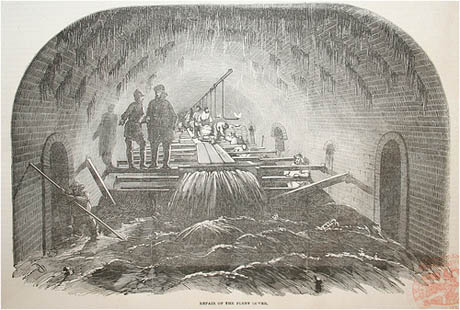

After the event, audience member and telecommunications strategist Jeremy Green got in touch to point me in the direction of the London iteration of cow tunnels: sewer pigs. Their first mention comes in the 1850s, when social researcher Henry Mayhew interviewed sewermen for his book, London Labour and the London Poor.

There is a strange tale in existence among the sewer-workers, of a race of wild hogs inhabiting the sewers in the neighborhood of Hampstead. The story runs, that a sow in young, by some accident got down the sewer through an opening, and, wandering away from the spot, littered and reared her offspring in the drain, feeding on the offal and garbage washed into it continuously. Here, it is alleged, the breed multiplied exceedingly, and have become almost as ferocious as they are numerous.

When Mayhew expressed disbelief, wondering why these pigs remained underground, the sewermen were apparently ready with a logical reply: “the only way the pigs could get out of the sewer would be to get to the mouth of it, which would require them to cross the Fleet ditch, against the rapid currents of which pigs would refuse to swim because of their obstinate nature.”

IMAGE: The Fleet sewer (one of London’s lost rivers) depicted during its repair in 1854, via.

IMAGE: The river Fleet near its source on Hampstead Heath, also sketched in the 1850s, via.

The swine surface again in the writings of Charles Dickens, as well as in a rather fantastic 1859 editorial from the Daily Telegraph, excerpted from the blog London Particulars:

Exaggeration and ridicule often attach to the vastness of London, and the ignorance of its penetralia common to us who dwell therein. It has been said that beasts of chase still roam in the verdant fastnesses of Grosvenor Square, that there are undiscovered patches of primaeval forest in Hyde Park and that Hampstead sewers shelter a monstrous breed of black swine, which have propagated and run wild among the slimy feculence, and whose ferocious snouts will one day up-root Highgate archway, while they make Holloway intolerable with their grunting.

IMAGE: A feral pig grazing in the open gutters of Rajasthan, via.

In the mid-nineteenth century, when the legend of the black swine was at its strongest, Hampstead was still a relatively rural farming village. Meanwhile, the city of London and its relationship with its agricultural hinterland were being transformed by the Industrial Revolution: railways, factories, and their attendant rural-urban migration. London’s population grew from one million in 1800 to 6.7 million by 1900, and with that growth came a radical renegotiation of the city’s food supply.

In other words, as in New York City, so in London: the increasing industrialisation of food spawned a sort of narrative resistance, in the form of pervasive myths of sewer pigs and cow tunnels buried deep beneath the city. Today, as planners, architects, and designers seek to make cities more healthy and sustainable by reconnecting urban dwellers to food production, perhaps they might tap into the power of these stories that bob up to the surface again and again, as if from a shared urban agricultural unconscious.

NOTE: Thanks, Jeremy — and thanks also to Liam Young of the Architectural Association and Geoff Manaugh of BLDGBLOG for organising a day packed with insights and ideas.