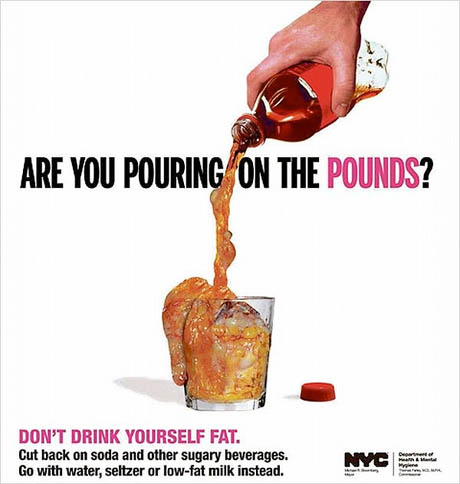

IMAGE: Deprived of a soda tax, New York City’s Department of Health has taken revenge with these ubiquitous, nausea-inducing ads, which show a fizzy drink turning into fat in the glass, complete with “those little blood vessels and things like that” (as described by Cathy Nonas, a dietitian with the DOHMH).

Having backed down once already, New York governor David Paterson recently made another last-ditch attempt to push a soda tax through the state legislature, alongside other revenue generators such as allowing wine sales in grocery stores and variable tuition fees at SUNY universities.

Although he was defeated (on all counts), his year-long campaign to tax sugary beverages (which included “-ades, punches and certain fruit nectars”) has sparked lively debate. The issues are fascinating and complex: depending on who you listen to, the proposed tax is regressive, damaging to New York businesses (customers would simply cross state lines to buy their Sprite in Jersey), and an utterly ineffective way to create the long-term environmental and behavioural changes that solving America’s obesity epidemic will require; or, a vital public health measure and valuable deficit-plug.

IMAGE: A Pepsi delivery lorry in Brooklyn. Photo by Earl Wilson for the New York Times.

Fortunately, the Center for Urban Pedagogy, whose excellent Bodega Down Bronx video formed the subject of an earlier Edible Geography post, has collaborated with the students of Bushwick’s Academy of Urban Planning to produce a primer (pdf) on the subject.

IMAGE: Cover of the Soda Census, by the Center for Urban Pedagogy and high school students from the Academy of Urban Planning.

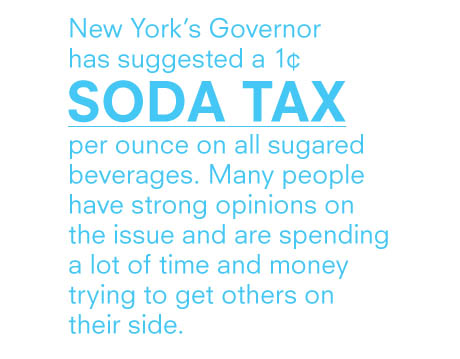

The booklet offers a handy how-to guide for soda-tax decision-making, starting with close readings of statements from the major players and a review of existing data, before moving onto the fun stuff: original, micro-local research.

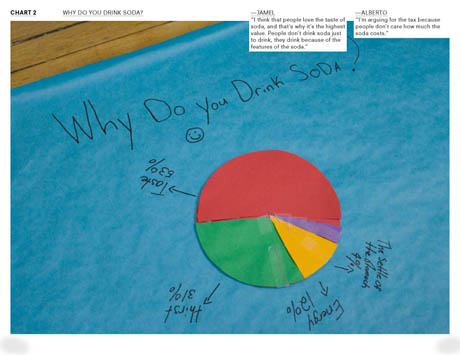

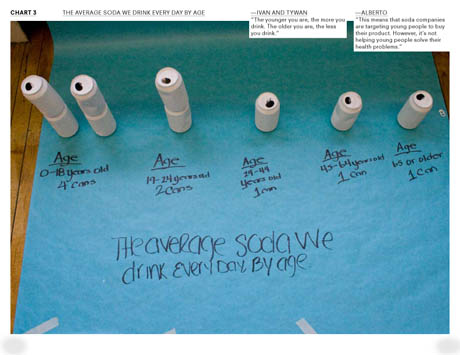

Students conducted a Bushwick soda census (“What kind of soda do you drink?” and “How much do you spend on soda per week?”), and then analysed their data with the help of compelling visualisations.

IMAGE: Soda census form, by the Center for Urban Pedagogy and high school students from the Academy of Urban Planning.

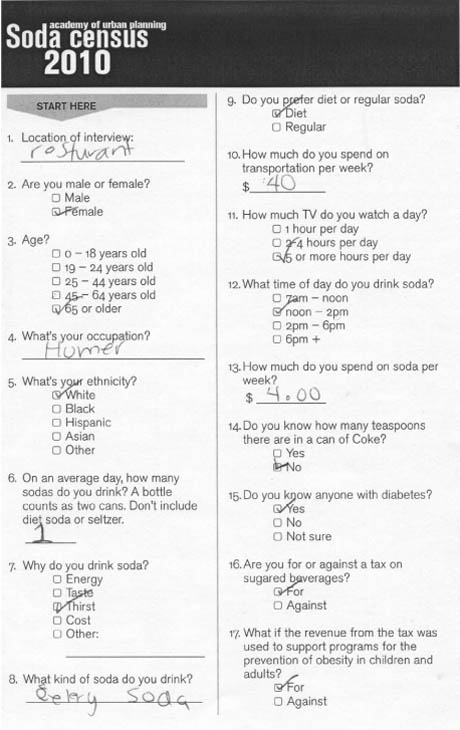

IMAGE: Why do you drink soda? Data visualisation by the Center for Urban Pedagogy and high school students from the Academy of Urban Planning. Jamel’s commentary: “I think that people love the taste of soda, and that’s why it’s the highest value. People don’t drink soda just to drink, they drink because of the features of the soda.”

Apart from the sheer charm of the visualisations and commentary (Ivan: “I’ve learned that picture graphs are more interesting than just numbers”), the project is both an awesome introduction to the power and perils of data (Walter: “The charts could be like this because we only asked people from Bushwick”) and a way into genuinely difficult questions about individual responsibility, public health, effective interventions, and root causes.

IMAGE: The average amount of soda we drink every day by age. Data visualisation by the Center for Urban Pedagogy and high school students from the Academy of Urban Planning. Alberto’s response: “This means that soda companies are targeting young people to buy their product. However, it’s not helping young people solve their health problems.”

IMAGE: Making charts at the Academy of Urban Planning.

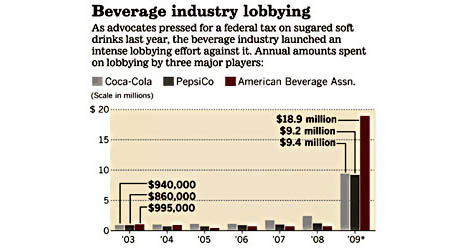

The students then use their data to assemble arguments for and against the tax, making the entire pamphlet a shining example of transparency in decision-making. And on that note, there are two interesting pieces of data that the students of Bushwick did not include, but which make the situation a little more opaque: the $140 million subsidy the federal government currently gives to support high fructose corn syrup production, and the $37.5 million dollars spent by soda industry lobbyists last year.

IMAGE: From “How The Soda Tax Died,” by Andrew Price for GOOD.

Which means that perhaps the most telling conclusion in the Bushwick Soda Census is this comment from Larae:

Many people would be affected by the tax, but the people who would be affected the most are the politicians, because if they vote for the soda tax, they might lose votes.