The American family dinner is an endangered custom with magical powers attributed to it. It is also, as cultural historian Abigail Carroll explains in her fascinating new book, Three Squares, “only about 150 years old.”

IMAGE: Three Squares, Abigail Carroll (jacket design by Nicole Caputo).

Subtitled “the invention of the American meal,” Three Squares is an engaging and eye-opening look at the economic and cultural forces that have shaped the country’s shifting formats of consumption over time — and, in turn, the changing meanings and value judgments that Americans have attached to those eating patterns.

Carroll starts with the casual, ad hoc chaos of pre-Victorian consumption. Although colonists saw a defined, three-meal-a-day structure as a way to differentiate their civilised society from the “savagery” of Native American feasts and fasts, in reality, their meals were “generally informal, variable, and socially unimportant affairs.” Food was often in short supply, and tables, chairs, knives, forks, and plates even rarer: Carroll notes that fewer than one in four seventeenth-century Virginia households had a table, and sharing a dinner bowl with a “trencher-mate” was standard practice until the late eighteenth century.

IMAGE: Trencher, c. 1500-1700, in the Victoria & Albert Museum collection, photographed by David Jackson.

Even more importantly, in a pre-industrial era where nearly everyone spent every day engaged in hard physical labour, eating was an opportunity to refuel, rather than demonstrate dining etiquette:

Food meant survival; it was energy and sustenance, and obtaining one’s fill was serious business. Not surprisingly, the shape and social trappings of the meal meant comparably little.

Then came the Industrial Revolution, and, with it, a new world of city-dwelling consumers whose relationship to food was now shaped by the demands of factory work schedules and the anonymity of urban life.

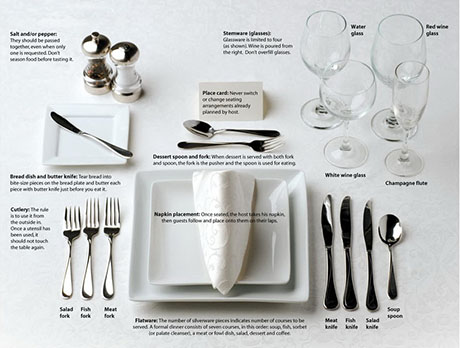

Obviously, people living in a large city could not possibly know everyone, the way they might have in a small town or village. Instead, they began to rely on social etiquette to manage interactions between strangers, but also display and judge class status. Dinnertime became both a training ground and showcase for Americans’ emerging code of polite manners.

IMAGE: From “Rules of Civility” in the Gentleman’s Gazette.

IMAGE: Lunch pails, 1880s, via The Smithsonian Magazine.

Meanwhile, as we’ve discussed on Edible Geography before, lunch is another legacy of industrialisation and urbanisation. Interestingly, Carroll fills in the other half of that story: the impact that eating outside of the house at mid-day had on the evening meal.

No longer laboring together as an economical unit, family members needed a new way to bond, and dinner fit the bill. With husbands, wives, and children inhabiting separate worlds during the day—office, factory, home, school—coming together around a table in the evening took on heightened significance. […] Communal consumption replaced cooperative production as the glue that held the family together.

In other words, the invention of lunch simultaneously served to ennoble the evening meal, leading to the semi-sacred status the family dinner holds today. Of course, this change didn’t happen overnight, leading to a couple of decades of confusion and awkward clashes in which “it was common for one family to dine in the evening while its neighbors dined in the afternoon.”

IMAGE: Freedom from Want, Norman Rockwell, 1943. According to Carroll, “whereas dinner had served as a vehicle of family cohesion of middle-class identity in the nineteenth century, in the twentieth, as Rockwell hinted, it became a way to connect with the nation.”

Carroll’s focus is the American meal, for which the Industrial Revolution was, indeed, revolutionary. What’s intriguing, though Carroll does not go into this, is that this seismic shift from lunch to dinner as the main meal of the day has not been universal. Other countries and regions, particularly ones that were slower to industrialise, still eat a big meal at mid-day, and a snack for dinner.

For example, in Mexico, where I spent the last two weeks as a guest of the new and wonderful Laboratorio para la ciudad (of which more very soon), the entire team went out for a large and leisurely four-course meal between 2 and 4pm each day, before rolling back to the office for another three-hour burst of activity, and a light snack for dinner. This meal pattern is increasingly touted by scientists as a healthier approach, and I found it suited me very well — the dreaded afternoon slump was replaced with a slow, sociable meal, while the dinner-less evening suddenly seemed like an oasis of free time, and there was none of the discomfort of going to bed on a full stomach. The only downside was a lack of opportunities to cook, which, of course, had its own upsides in a corresponding lack of grocery shopping or dishes to be done…

IMAGE: The main dish of a Mexico City comida corrida, photographed by author David Lida for his blog, where he also documents the soup and rice course that precede it, the agua fresca and tortillas that come with, and the dessert that follows.

In any case, the point that Carroll fails to make is that although industrialisation and urban life reshaped the American meal, that transformation was not inevitable. Perhaps it says something about the American (and Northern European) approach to food that consumption was made to conform to the demands of work, rather than vice versa (perhaps it also has to do with the pace at which a particular society industrialised).

Of course, the changing nature of work was not the only influence shaping the evolution of the American meal. Carroll describes a case of Anglophilia in the eighteenth century, which lead to the displacement of vegetables on the American plate by roasted meat, and a subsequent fashion for everything French, which fell by the wayside when servants stopped being the norm, leaving a legacy of dessert. Technological innovations also had a huge impact, with the rise of the food processing industry coming to the rescue of the newly servant-less middle-class housewife. Meanwhile, the rise of a defined breakfast, lunch, and dinner threw their antithesis—snacking—into sharper focus, as a transgressive form of consumption.

The snack and the meal cannot be understood apart from one another. They emerged out of the same historical moment, and […] their stories are wholly intertwined. […] Snacking posed a threat to the meal; it subverted the family’s fellowship around the table and the middle-class values that proper evening meals had come to embody.

Finally, although Carroll’s concludes that “perhaps the family meal is worth saving,” the book’s lasting value, at least for me, lies in its reminder that the three-meal structure is “only a cultural heirloom, not an ordinance of nature” — and thus open to intentional reinvention, as well as reactive evolution.

IMAGE: The Evanston Community Kitchen was founded during World War I, and, at its peak, delivered 500 meals each week.

Intriguingly, Carroll briefly describes a flurry of alternatives to the family dinner that emerged at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth. These experiments in cooperative housekeeping, centralised food preparation, and even community dining took varied forms: at a dining club in Carthage, Missouri, sixty members pooled resources to pay for manager, two cooks, waitresses and a dishwasher, and ate dinner in one large room, but with each family unit at separate tables; meanwhile, in New Haven, Connecticut, the Twentieth Century Food Company was a prototype of today’s meal delivery services, although it floundered in the face of logistical challenges and the failure of its “asbestos-lined food container” to keep food reliably hot or cold.

Unsurprisingly, “cooperative housekeeping, with its feminist and socialist underpinnings, never flourished in the United States,” though for a brief period at the turn of the last century it seemed as though it might. Carroll speculates as to the potential impact of this alternative history:

Had it become mainstream, cooperative housekeeping might have set the American dinner on a very different trajectory than the one that brought the meal to where it is today. Kitchen-less houses might have become the norm; apartment dwellers might have learned to rely on centralized food services included in monthly rent; cooking might have transformed into an occasional leisure activity. At the same, the family dinner as nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Americans knew it might have dissolved, along with the institutions that came to be associated with it: proper manners, polite conversation, and familial accountability.

IMAGE: Americans eat nearly 20 percent of their meals in cars, according to John Nihoff, Professor of Gastronomy at the Culinary Institute of America.

Carroll’s last sentence seems a bit over the top: after all, mealtimes are hardly the only occasion for developing a sense of familial accountability (assuming that is even a desirable quality). If, as we’re endlessly told, the family dinner is in crisis, then, rather than simply wringing our hands and bemoaning the decline of table manners, we should instead see this as an opportunity for a much more thoughtful re-invention of the way we eat. In Three Squares, Carroll shows us that way we work and live shapes meals. Perhaps the reverse is also true, and we are how we eat.