IMAGE: Ministry of Defence Main Building, photograph by JoanneB via Wikipedia.

Like the Pentagon, its better-known counterpart in the United States, Britain’s Ministry of Defence building is a fairly mundane, if gigantic, office block camouflaging a much more exciting subterranean realm of secret tunnels, bunkers, and — at least in the MoD’s case — a perfectly preserved Tudor wine cellar.

IMAGE: Henry VIII’s wine cellar, photograph by Nicola Twilley. The cellar is apparently occasionally used to host Ministry of Defence dinners and receptions, but is otherwise off-limits to the public other than by special request.

This stone-ribbed, brick-vaulted undercroft was built in the early 1500s by Cardinal Wolsey, as part of a suite of lavish improvements to York Place, the Westminster residence of the archbishops of York since the thirteenth century. The additions, which also included a gallery, presence chamber, and armoury, were intended to make York Place into a palace splendid enough to host the King. They succeeded well beyond Wolsey’s intentions: when Wolsey fell from favour, due to his inability to secure the papal annulment Henry VIII needed in order to marry Anne Boleyn, the King decided to move in.

IMAGE: Whitehall Palace, circa 1670s. Painting by Hendrik Danckerts. The Bridgeman Art Library, via the BBC.

IMAGE: Fisher’s ground plan of the Palace of Whitehall in London in 1680, showing the wine cellar north of the Great Hall, via Wikipedia.

York Place became the Palace of Whitehall, the principal residence of the English monarchy in London for nearly two hundred years, and Wolsey’s expansive cellar (he apparently received the first delivery of Champagne ever exported to England) became King Henry VIII’s Wine Cellar, the name by which it is still known today.

Curious as to how a Tudor wine cellar had become entangled in the bowels of Britain’s military headquarters, I left a message on the Ministry of Defence switchboard to see whether it might be possible to visit. To my surprise, a charming officer called me back straightaway, and told me that he’d be happy to escort me as he was quite keen to see the wine cellar himself, having regularly passed signage for it on his way to the gym.

IMAGE: The exterior of Henry VIII’s wine cellar in the MoD basement, photograph by Nicola Twilley.

We met at reception, passed through an airlock, and took a series of narrow back staircases and corridors to arrive at the large, fluourescent-lit concrete void in which Henry VIII’s cellar now floats, umbilically attached to its new host by a large aluminium HVAC duct.

IMAGE: The exterior of Henry VIII’s wine cellar in the MoD basement, photograph by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: The exterior of Henry VIII’s wine cellar in the MoD basement, photograph by Nicola Twilley.

In 1698, laundry left to dry over an open fire started a blaze that burned the Palace of Whitehall to the ground. It was never rebuilt, and the land was leased, first for townhouses in the eighteenth century, and then, when Parliament decided to centralise the major departments of state in the 1850s, for purpose-built government offices. The wine cellar remained intact but largely forgotten until the War Office, which later became the Ministry of Defence, began work on a new building in the 1930s.

IMAGE: Interior of Henry VIII’s Wine Cellar. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: Brick vaulting, Henry VIII’s Wine Cellar. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

Writing in a 2010 issue of the AA Files Andrew Crompton describes the design of the poetically named MoD Main Building, which was “so slow in coming out of the ground that it became know as the Whitehall Monster.” In addition to the understandable delay caused by World War Two, Crompton ascribes its astonishing twenty-one year construction to the fact that the MoD Monster has “embedded within it a series of spaces that seem to have more to do with sympathetic magic than functional architecture.”

Included among these embedded spaces are a Gothic crypt, a crooked staircase that leads nowhere, “five very fine eighteenth-century interiors” — the first ever preserved outside of a museum — and, of course, Henry VIII’s long-lost wine cellar.

IMAGE: Interior of Henry VIII’s Wine Cellar. The barrels are historical reconstructions to represent how wine was stored in Tudor times. Henry VIII’s court consumed something like 300 barrels of wine each year, mostly exported from France and delivered to the palace by river. Interestingly, the wine was drunk very young by today’s standards — an August harvest might be on the table by November — and it was carefully blended with water, honey, and spices to mask its increasing sourness, as half-drunk casks allowed air into contact with the wine, which gradually oxidised into vinegar. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

Incorporating the wine cellar into the new building was not simply a matter of building around it. In the intervening years, the road level had sunk, leaving the cellar half-exposed above ground. To make matters worse, the cellar did not sit entirely within the footprint of the Ministry of Defence building, but instead protruded slightly from its western edge, obstructing the proposed route of the new Horse Guards Avenue.

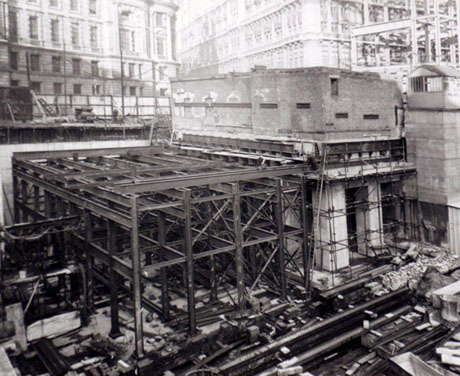

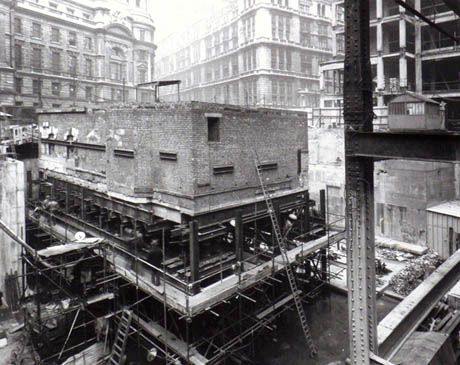

IMAGE: Moving Henry VIII’s wine cellar. Crown Copyright.

IMAGE: Moving Henry VIII’s wine cellar. Crown Copyright.

An interpretive panel on a ramp outside the cellar explained that the “decision was made to keep the Cellar on its historic site” — more or less – but that, due to the softness of the Tudor bricks, the seventy-feet long, thirty-feet wide structure could not simply be dismantled and reassembled a few feet lower down and further west. Instead, the general contractors, Trollope and Colis, “embalmed the Cellar in protective layers of concrete, steel and brick and placed it on mahogany cushions, carriage rails and steel rollers.”

The structure was moved 43.6 feet to one side onto a specially designed steel frame and a 20ft hole was then dug on its original site. The 1000-ton building was then lowered on screw jacks and then moved back 33 ft 10 inches to its present position. This prodigious piece of engineering skill was completed without any damage to the structure.

IMAGE: Interior of Henry VIII’s Wine Cellar. Photograph by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: Photograph from David Moore’s The Last Things series, which documents a Ministry of Defence Crisis Command Bunker buried beneath the Main Building, widely supposed to be PINDAR, via Wired.

Nineteen feet down and nine feet to the west of its original site, Henry VIII’s cellar floats incongruously in the labyrinthine concrete sub-basements of the Ministry of Defence like some kind of gallstone, the crystallized accretion of the site’s history. And thus this last fragment of Henry VIII’s splendid palace lies, preserved by burial, alongside hidden bunkers that anticipate nuclear apocalypse, and, of course, the Ministry of Defense gym.

Many thanks to Major Nick Barton for the tour.