These colour lithographs were originally made in 1850 at the request of Walter S. Sherwill, an army officer who served as a British “boundary commissioner” in Bengal. According to Ptak Science Books, these particular reproductions were taken from an article exploring the economic and infrastructural marvels of the Indian opium trade in an 1882 supplement to Scientific American.

They show the main opium receiving, production, and distribution center of the East India Company in Patna, a town in the north-western Bihar province of India. From these vast mixing rooms and examining halls, the Company claimed to produce roughly 13,000,000 pounds of opium annually, which was then shipped down the Ganges to Calcutta, and from there to China.

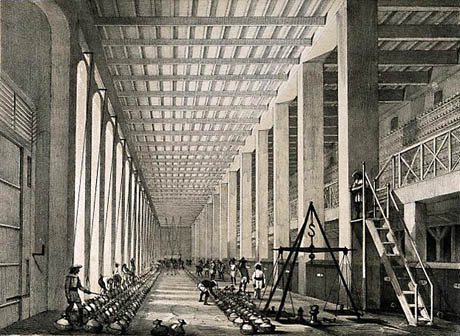

The image above shows the Examining Hall of the opium factory, where, Scientific American reports, “the consistency of the crude opium as brought from the country in earthen pans is simply tested, either by the touch, or by thrusting a scoop into the mass. A sample from each pot (the pots being numbered and labelled) is further examined for consistency and purity in the chemical test room.”

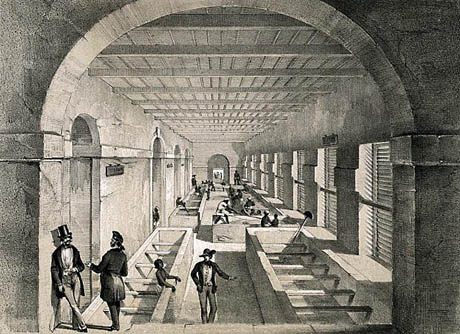

In the Mixing Room (above), which otherwise looks like a somewhat spartan bathhouse, “the contents of the earthen pans are thrown into vats and stirred with blind rakes until the whole mass becomes a homogeneous paste.” Next stop, according to Scientific American, is the high-ceilinged Balling Room, where the opium paste is shaped into small spheres:

In the Mixing Room (above), which otherwise looks like a somewhat spartan bathhouse, “the contents of the earthen pans are thrown into vats and stirred with blind rakes until the whole mass becomes a homogeneous paste.” Next stop, according to Scientific American, is the high-ceilinged Balling Room, where the opium paste is shaped into small spheres:

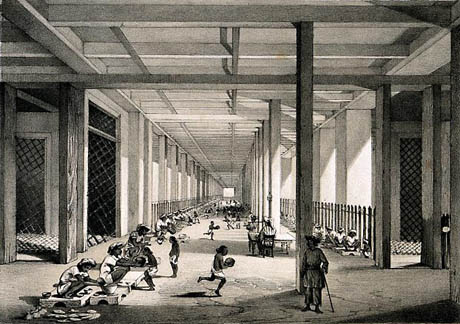

Each ball-maker is furnished with a small table, a stool, and a brass cup to shape the ball in a certain quantity of opium and water called ‘Lewa,’ and an allowance of poppy petals, in which the opium balls are rolled. Every man is required to make a certain number of balls, all weighing alike. An expert workman will turn out upwards of a hundred balls a day.

After this, the balls are taking to the Drying Room, where each is placed in an individual earthenware cup. The image below shows “men examining the balls, and puncturing with a sharp style those in which gas, arising from fermentation, may be forming.”

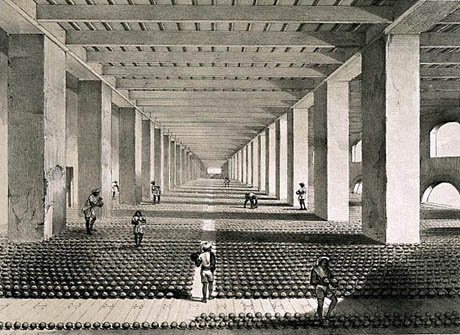

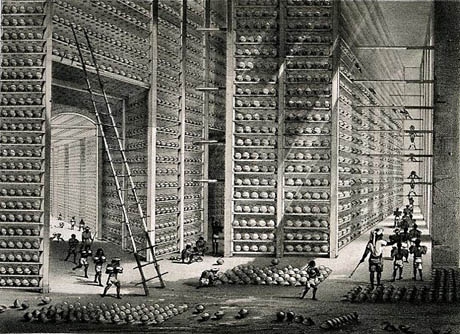

The finished opium balls are stored before shipping in the Stacking Room, where “a number of boys are constantly engaged in stacking, turning, airing, and examining the balls. To clear them of mildew, moths or insects, they are rubbed with dried and crushed poppy petal dust.” Finally, the balls are transferred into cardboard boxes and loaded into ships bound for Calcutta.

This factory — “the architecture of 13,000,000 pounds of opium production,” as Ptak Science Books calls it — is part of a larger British colonial landgrab fueled, at least in part, by pursuit of the immense profits to be earned from an unrestricted drug trade. As Amitav Ghosh, in an interview about his novel, Sea of Poppies, explains, “The Ghazipur and Patna opium factories between them produced the wealth of Britain. It is astonishing to think of it but the Empire was really founded on opium.”

While the buildings at Patna now house a government printing press, the Ghazipur opium factory to which Ghosh refers both was and still is the largest opium factory in the world. It has remained pretty much unchanged since Rudyard Kipling described it in 1888, according to a report in the Bihar Times, and has generated a profit every year since it was founded in 1820. The USA and Japan are the largest opium importers, apparently, having inherited the crown from the Soviet Union following its collapse.

In any case, both factories, as well as the fields of poppies that surrounded them, and even the skyscrapers of Hong Kong, form a living archaeology of the incredible economic influence, infrastructural legacy, and spatial impact of the opium trade. Curiously, in Afghanistan today, one of the reasons why opium is more economically attractive to farmers is infrastructural and architectural: drug traffickers pick up the poppies at the farms, whereas growing a food crop would require farmers to build storage facilities and transport their produce to market.

It’s also interesting to consider these grand, temple-like opium factories alongside contemporary spaces of drug production: the foreclosed tract homes that house America’s meth labs, or the tunnels carved out as part of the U.S.-Mexico border smuggling wars. Perhaps a more accurate analogy is Jeff Wilcox’s “vision” for an industrial-scale marijuana farm and processing facility on a 7.4 acre business park in Oakland (already rewired by PG & E to supply banks of power-hungry grow lamps), as opposed to the unregulated encampments of barbed wire, plastic tubing, and leaky generators currently hidden in Mendocino and Humboldt County’s redwood forests.

Thanks to the PLoS Neuroanthropology blog for the link to the Ptak Science Books post.