VIDEO: CROPS, Gerco de Ruijter, 2012.

Dutch photographer Gerco de Ruijter’s stop-motion film, CROPS (previously featured on BLDGBLOG), cycles through a seemingly endless sequence of centre pivot-irrigation crop circles, as seen by satellite.

As BLDGBLOG notes, as the stills succeed each other, their flickering variations in crop colour, furrow frequency, and pivot position occasionally seem to “promise a strange new form of time-keeping, with the irrigation equipment itself ticking like a stopwatch,” and at other times look more like “a record spinning wildly on its platter.”

Each circular plot is shown at the same size, cropped to fill the square frame — the fallow corners marking the difference between the economic logic of irrigation technology and the grid structure imposed on the landscape by the U.S. survey.

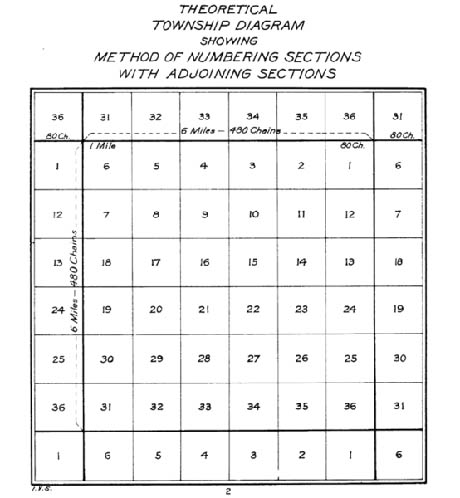

IMAGE: U.S. Bureau of Land Management, via Wikipedia.

These overlooked corners make up a not insubstantial percentage of a farmer’s available land. On a typical 160 acre “quarter section” in the American mid- and southwest, tessellating pivot circles will leave up to 24 acres, or 15 percent of each field, thirsty.

IMAGE: Pivet [sic] Irrigation near the One Hundred Circle Farm and the McNary Dam on the Columbia River, Washington, Emmet Gowin, 1991.

The question of wasted corners is addressed in this fascinating oral history of Robert Daugherty, the farm manufacturer who bought Frank Zybach’s 1952 patent for the first centre-pivot irrigation machine and made the technology work at a commercial scale:

Talk to a farmer about his square 160 acre field and we want to put a circle in it, [he says,] “What are we going to do about the corners?” Well, we can’t do anything about the corners.

That was in the beginning. Today we can certainly solve that problem because we have the means of putting an attachment on the end of a typical system. It will swing out and retract as the system goes around so that the corners are covered.

Well, the problem with that is that arm that swings out and all the equipment that goes with it is quite expensive. So, farmers don’t generally buy those unless they are growing valuable crops. And some crops like potatoes, as an example, where you’re talking somewhere between $2- and $3,000 per acre. Then, it makes sense to put on a corner system.

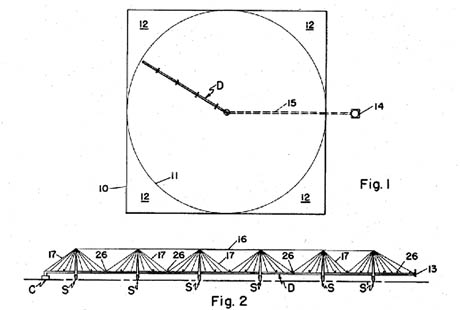

IMAGE: Frank Zybach’s original patent drawing.

IMAGE: Bob Daugherty’s company, Valmont Industries, Inc., has offered a corner system since the 1970s.

User feedback aired in online farming discussions, such as AgTalk or The Combine Forum, seems to concur: the circle has yet to be satisfactorily squared. Corner swing arms are expensive, in part because they follow a low-voltage wire that has to be be buried around the entire perimeter of the field, and they are also significantly less reliable. The result is a delicate equation that balances land value, potential yield without irrigation, water availability, and crop prices to determine whether the corners are worth the hassle of a corner swing system or not.

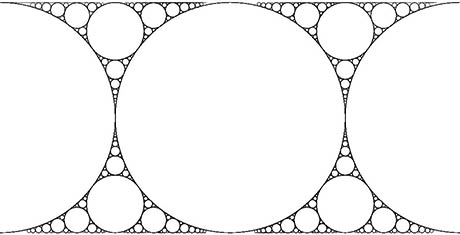

Mathematics offers another possible solution: Farey-Ford circle packing, a tessellation technique that reportedly has “many interesting properties” in fields as abstruse as hyperbolic non-euclidean geometry and number theory. In agricultural terms, this translates to: “Put a small pivot in the corners, you will be happier and will have time to take the kids fishing instead of working on the corner arm,” according to “spudz52,” a farmer in St. Anthony, Idaho, commenting on an AgTalk thread.

IMAGE: Farey-Ford circle packing via the Illinois Geometry Lab.

Elsewhere, a Utah farm family has found a niche leasing corners from their neighbours to grow less thirsty crops or graze cattle. Hay & Forage Grower reports on the Bunderson siblings, “Corner Kings of the Southwest,” who have built a larger-than-average farm entirely out of discontinuous pivot discards:

Since 2005, the Bundersons have been leasing 20 corners on 10 pivot circles from a local crop farmer to grow alfalfa and alfalfa-grass hay. The corners vary in size from eight to 10 acres. In all, the Bundersons work 190 acres spread out over a four- to five-mile radius.

And, increasingly, ecologists are preaching the potential of pivot corners. In a simplified landscape of monoculture crop circles, the corners can restore complexity: left as native perennial grassland or managed as early successional habitat, these concave triangles can provide valuable habitat for bees, birds, and predatory insects to support crop pollination and natural pest control. Sewn together across an agricultural landscape, the corners can even offer movement corridors for migrating species.

Perhaps pivot corners could become the SETI@Home of agricultural biodiversity: the large-scale, distributed provision of ecosystem services, humming quietly away in the leftover spaces of industrial crop production.

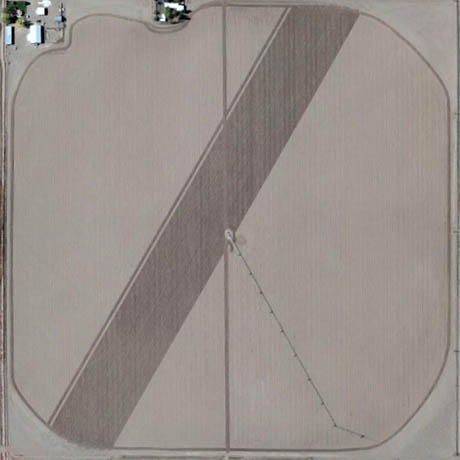

UPDATE: After reading this post, deRuijter went back through his archive of Google Earth images, looking for the strange pivot circles he had previously discarded because “the circles were just too big and they seemed squeezed from the sides.”

On some, you can actually see the corner swing arm, following its wire track to extend the circle.

De Ruitjer even found an example of “circle packing”: smaller pivots, filling in between the larger plots:

But these fixes are the exception, rather than the rule. Writing on his blog, de Ruijter confesses he is as surprised by the quantity of corner land left over as I was: “For me, living in the Netherlands, this is hard to understand. A Dutch farmer will do anything to use every percentage of the land he owns.”