IMAGE: Bompas & Parr’s Parabolic Sherry is available for purchase at the Pop Rock Moon Shop.

If you’re in London on Sunday, don’t miss “A Brief History of Drinking in Space” with Sam Bompas of Bompas & Parr and David Lane of The Gourmand:

To date, there has been relatively little consumption of alcohol in space and on the moon, but that could be set to change. With space tourism taking off, new lunar missions on the horizon and manned expeditions aiming further into space – with all its stresses – could a new era of zero gravity libations be next? From Buzz Aldrin’s legendary Holy Communion on the moon to sherry experiments aboard Skylab and ceremonial ‘vodka’ consumption aboard the ISS, we’ll discuss the secret history of a slightly tipsy space age and ask what role our favourite poison will play in the future colonisation of the moon.

Better still, the £5 ticket price includes the chance to sample Bompas & Parr’s Parabolic Sherry, a limited edition, plastic-pouched tipple based on Skylab-era research about alcohol in space.

The story behind NASA’s brief embrace of extraterrestrial sherry is a curious one. In the early seventies, the agency’s focus was shifting from short, Moon-focused missions to possibility of longer-term inhabitation of space. A revamped menu was among the most pressing challenges: food on the Gemini and Apollo programs came in dehydrated cube form, or squeezed from a pouch, and was universally regarded as inedible. According to Ben Evan’s book, At Home in Space: The Late Seventies into the Eighties, in May 1969, Don Arabian, NASA’s spacecraft project manager, tried living on Apollo fare for three consecutive days, and subsequently reported that he had “lost the will to live” and that, in particular, “the sausage patties tasted like granulated rubber.”

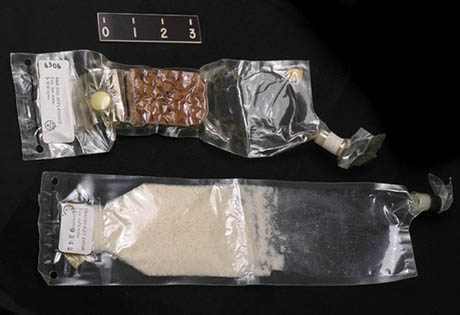

IMAGE: Apollo-era space food, via.

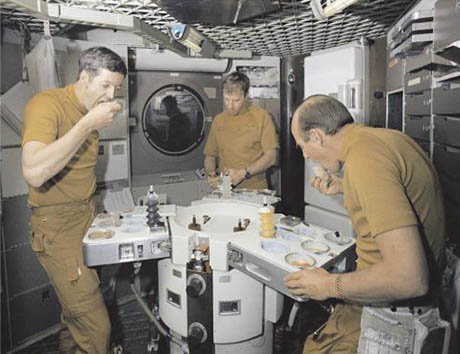

After a year of working on the food program for Skylab, the United States’ first space station, Evans reports that “the situation had improved significantly: the station would include both a freezer and an oven and foods would be provided in five varieties — dehydrated, intermediate moisture, ‘wet-packed,’ frozen, and perishable.”

Spaghetti, prime ribs, ice-cream, and — for a brief moment — alcohol were all on the menu.

The tough role of Space Sommelier fell to Charles Bourland, who spent more than three decades at NASA Johnson Space Center developing food and food packages for spaceflight, and shared his recipes and reminiscences in The Astronaut’s Cookbook:

My boss was Mormon and consequently, the job of heading the wine selection process for the Skylab missions fell to me. Selecting a wine was an interesting project for the people in the food laboratory, and we had no shortage of volunteers for the taste panel.

After consulting with several professors at the University of California at Davis, it was decided that a Sherry would work best because any wine flown would have to be repackaged. Sherry is a very stable product, having been heated during the processing. Thus, it would be the least likely to undergo changes if it were to be repackaged.

The winner of the space Sherry taste test was Paul Masson California Rare Cream Sherry. A quantity of this Rare Cream Sherry was ordered for the entire Skylab mission and was delivered to the Johnson Space Center. A package was developed that consisted of a flexible plastic pouch with a built-in drinking tube, which could be cut off. The astronaut would simply squeeze the bag and drink the wine from the package. The flexible container was designed to be fitted into the Skylab pudding can.

IMAGE: “Skylab’s first crew — from the left, Joe Kerwin, Paul Weitz, and Pete Conrad — prepare and eat food in a mockup of the wardroom in the spring of 1973.” Photograph from At Home in Space: The Late Seventies into the Eighties by Ben Evans.

An article in The Milwaukee Journal, dated August 1, 1972, gleefully reported the news that “the era of prohibition is about to end in space.” Dr. Malcolm Smith, a nutritionist on Bourland’s team, explained that the wine chosen was American, that astronauts were rationed to just four ounces every four days, and that “the question of whether wine promoted better health was still open.”

I would tend to believe that there is some value besides pure energy, either in the calming effect or promoting digestion. Somewhere in there, there’s probably a beneficial effect from wine.

And yet the sherry never went to space.

IMAGE: Food Lab personnel Jane McAvin and Gloria Mongan test food packages on the zero G plane (NASA photograph).

First of all, early tests in NASA’s low-gravity, “Vomit Comet” plane, designed to see whether the packaging worked in weightless conditions, produced unfortunate results, as Bourland recalled in his official oral history:

As it turned out, the odors released by the wine, combined with the residual smell of years-worth of people getting sick on the plane, had an unplanned effect on the crew. Many grabbed for their barf bags.

In response, NASA surveyed the crew as to whether they wanted the sherry on board, and “it was about half and half. They didn’t really care.”

The final nail in the drinks cabinet coffin came when Skylab 4 commander, Gerry Carr, mentioned the presence of alcohol on the menu in a public lecture, and NASA received a flurry of angry letters from the general public. As the Milwaukee Journal article reports, the team had anticipated that the sherry plan might not go over well:

“Let’s just say that no one here is enthused about publicizing this thing any more than necessary,” said scientist-astronaut Edward G. Gibson, who will fly on the third Skylab mission. “The problem is that you have got some extremists around and we (astronauts) kind of represent a form of purity. As soon as you taint that purity with alcohol, they really get upset,” Gibson said.

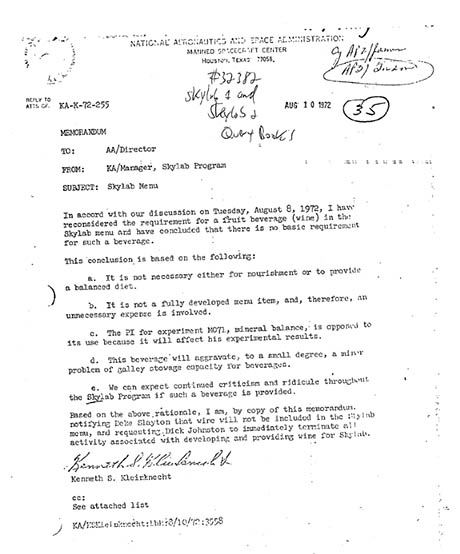

Gibson’s comments were prescient. The official end of NASA’s alcohol program came just ten days later, in a memorandum from Kenneth S. Kleinknecht, Skylab’s manager in Houston, to Chris Kraft, director of the Johnson Space Center:

In accord with our discussion on Tuesday, August 8, 1972, I have reconsidered the requirement for a fruit beverage (wine) in the Skylab menu and have concluded that there is no basic requirement for such a beverage.

This conclusion is based on the following:

a. It is not necessary either for nourishment or to provide a balanced diet.

b. It is not a fully developed menu item, and, therefore, an unnecessary expense is involved.

c. The PI for experiment MO71, mineral balance, is opposed to its use because it will affect his experimental results.

d. This beverage will aggravate, to a small degree, a minor problem of galley stowage capacity for beverage.

e. We can expect continued criticism and ridicule throughout the Skylab Program if such a beverage is provided.

Based on the above rationale, I am, by copy of this memorandum, notifying Deke Slayton that wine will not be included in the Skylab menu, and requesting Dick Johnston to immediately terminate all activity associated with developing and providing wine for Skylab.

IMAGE: The sherry death knell, as seen in a faxed response to a 2006 Freedom of Information Act request by space historian Jennifer Ross-Nazzal.

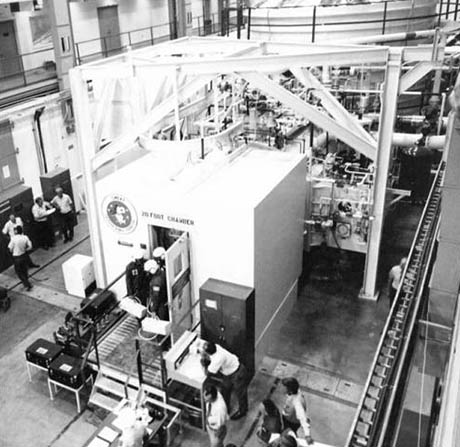

IMAGE: The SMEAT chamber. Photograph from Homesteading Space: The Skylab Story.

The good news is that the sherry did not go to waste. At the time the fateful decision was being made, a crew of astronauts were preparing to spend fifty-six days in a vacuum chamber, simulating a Skylab stay as closely as possible. The experiment was called SMEAT (Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test), and in Homesteading Space: The Skylab Story, astronauts Owen Garriott and Joe Kerwin, writing with co-author David Hitt, describe the role that sherry played in it:

Fortunately for the SMEAT crew, however, by the time the decision was made to remove the sherry from the Skylab menus, the SMEAT menus had already been made out, and it was too late to go back through the process of completely rebalancing the various nutritional factors that would have to be changed if the sherry was removed. “We had it,” Crippen said, “and we really looked forward to it.”

Of course, not all countries share the United States’ prohibitionist tendencies. Russia, has its own, differently dysfunctional relationship to alcohol, which, as Mir space station resident Alexander Lazutkin explained to NBC, means that cognac is prescribed to cosmonauts on extended missions in order “to stimulate our immune system and on the whole to keep our organisms in tone.”

IMAGE: Russian cosmonauts celebrating with cognac after dealing with a fire emergency on the Mir space station. Alexander Lazutkin is on the far right. The picture was taken by NASA astronaut Jerry Linenger, who did not drink.

As it turns out, there is some scientific evidence for the benefits of alcohol in space. A 2011 paper published in the journal of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology concluded that resveratrol, a phenolic compound found in red wine, “could be envisaged as a nutritional countermeasure for spaceflight,” following an experiment that hung rats upside down to simulate the bone density loss that accompanies zero-gravity living.

Sadly, both cognac and sherry are made from white wine grapes, and contain very little resveratrol. But, as Sam Bompas and David Lane point out, with longer term missions to Mars on the horizon, as well as Virgin Galactic-style space joyrides, perhaps it’s time for a new crew of Space Sommeliers to step up. If you manage to get to the event on Sunday, please report back!