Despite persistent urban myths to the contrary, chewing gum is, technically speaking, edible. However, doctors do agree that it is not usually wise to swallow it, due to the risk of “gum-based gastrointestinal blockages.” Given that in 2005, Americans chewed, on average, 160-180 pieces or about 1.8 lbs of gum per person, per year, with relatively few swallowing incidents, the resulting post-masticatory waste probably adds up to more than 250,000 tons annually.

Inevitably, disposing of this sticky mass poses some challenges.

IMAGE: Seattle’s “gum wall,” one of the city’s “top attractions,” via.

In 2003, a UK Parliamentary briefing note titled Chewing Gum Litter framed the issue in practical terms:

Most consumers dispose of their chewing gum responsibly. However, where chewing gum is dropped onto pavements it sticks firmly to the surface as it dries. Chewing gum does not break down over time and so the deposits gradually accumulate.

Pounded smooth by pedestrians, discarded chewing gum debris thus forms the dominant decoration of the urban floor, a soot-black snot speckled across asphalt or paving stones’ shades of grey. Writing in The Guardian in 2005, journalist Tim Adams reported that an incredible ninety-two percent of Britain’s urban paving stones have gum stuck to them.

IMAGE: London’s splotchy streets, via the BBC.

For most of us, this black-on-grey dapple is so ubiquitous as to be invisible; it scarcely registers as litter. Intriguingly, shortly before his suicide, writer, chemist, and Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi became mildly obsessed with the gum beneath his feet, analysing it to create an alternative cartography of alimentary intention:

Gum can be found everywhere, but a more attentive examination reveals that it reaches maximum density in the vicinity of the most frequented bars: the chewer who is headed there is forced to spit out to free his mouth. As a result, the stranger, not familiar with the city, could find these places following the direction of the more thickly massed gum blobs, in the same way as sharks find their wounded prey by swimming in the direction of increasing concentrations of blood…

IMAGE: An area of heavy concentration in New York, via.

However, for those of an equally observant, but more hygienic, bent, dead gum blotches form a particularly intractable irritant; an urban disfigurement that is more pervasive than graffiti, cigarette butts, or even fast-food litter. Last summer, London’s Mayor, Boris Johnson, compared his reaction to this “awful self-inflicted impetigo” to the emotions Leonardo da Vinci would experience if he saw “black stubble on [the Mona Lisa’s] lovely cheeks and chin,” or the feelings of Wimbledon’s groundskeeper if “200 moles had simultaneously erupted through the grass of Centre Court.”

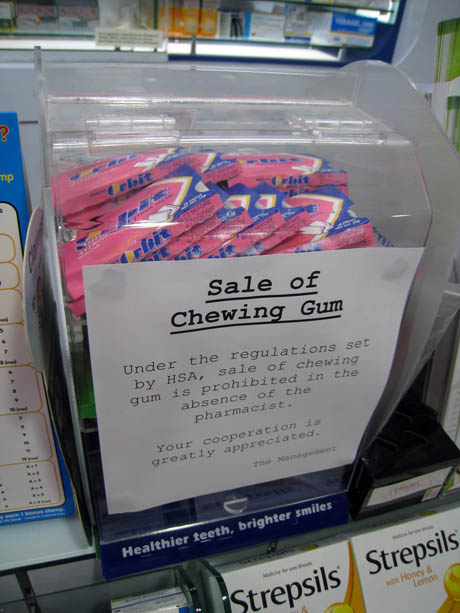

What’s more, the options for dealing with it are all somewhat unsatisfactory, although they vary in their effectiveness, practicability, and cost. On the prevention side, the city-state of Singapore has provided the best-known and most draconian example by banning the sale, import, and chewing of gum altogether in 1992. When BBC reporter Peter Day suggested that, in fact, chewing gum stuck to the pavements “might be a sign […] of creativity,” former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew quickly set him straight: “If you can’t think because you can’t chew, try a banana.”

IMAGE: “Medicinal” chewing gum on sale in a Singapore pharmacy, via LoLo Eatable.

However, the experiment was terminated in 2002, after just ten years, when intense lobbying pressure by Wrigley’s forced Singapore to allow the sale of “medicinal” gum as a pre-condition to signing a free trade agreement with the United States.

That same year, in the United Kingdom, where gum litter and hoodie-wearing are treated as serious social nuisances and tackled with a Bratton-esque “broken windows” fervour, Defra (the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs) proposed a voluntary scheme to restrict the sale of chewing gum in areas with particularly heavy deposition — a half-hearted attempt that was quickly shot down by gum manufacturers and local authorities alike.

IMAGE: Gum targets attached to lamp-posts and disposable GumVelopes are just two of millions of designs that attempt to solve the gum litter problem through prevention.

Lacking the cojones to pass and enforce an outright ban, the UK has resorted to a mix of behavioural nudges (including specially designed gum disposal bins and boards) and sticks, such as the hiring of “gum-wardens” capable of imposing £50 on-the-spot fines for gum littering. When Tim Adams of The Guardian spoke with Nick and Trevor, Maidstone City Council’s erstwhile gum-wardens, back in 2005, their efficacy seemed somewhat limited:

The key to successful gum-wardening, Nick explains, is not to walk purposefully, but to amble. In this way, they cover maybe eight miles a day. However, in the six weeks that they have been patrolling the city’s pedestrianised shopping area, with the back-up of 24-hour CCTV, so far Nick and Trevor have seen one man in the act of dropping gum. They threatened him with a £50 fine, though, in the end, they could not make the fine stick because it was not clear whether ‘the target’ had dropped his gum on public or private property.

IMAGE: The gum-warden team policing the streets of Oxfordshire, via the BBC.

In accordance with the unfortunate truth that it is easier to surmount almost any technological challenge than to change human behaviour or interfere with corporate profits, the holy grail of gum litter prevention is the development of non-sticky or biodegradable gum.

Last October, after years of research and with more than £5 million spent on the quest by Wrigley’s alone, scientists at Bristol University launched a chewy, tasty spearmint gum that dissolves into a fine powder after six months of sidewalk exposure. I have yet to see Rev7 gum on sale, but the company has successfully secured a round of venture capital financing, and CEO Roger Pettman told Forbes that “interest so far from convenience store operators has been ‘very promising.'”

IMAGE: Gum removal in Winchester, via.

While we wait for its biodegradable cousin to take off, removal remains the only 100 percent effective option for those who find Johnson’s “monstrous plague of chewing gum blotches” sufficiently revolting to justify spending between £0.45 and £1.50 per square metre to steam, spray, dissolve, or scrape the urban skin clean. In 2005, Defra estimated that local authorities spent a total of £150 million per year on gum removal, or three times more per gum blotch than each stick or piece cost when fresh. London spends £8,500 a pop to de-gum Trafalgar Square alone.

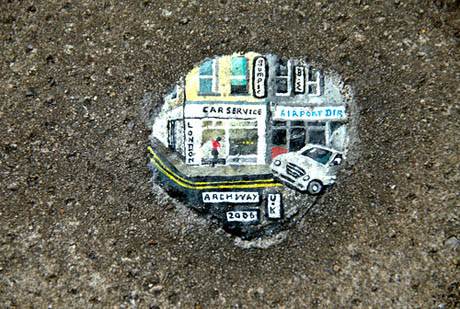

IMAGE: Ben Wilson at work in Muswell Hill, via Flickr user nevilley.

IMAGE: Ben Wilson painting a chewing gum blotch, via Flickr user Jansos.

A strict cost-benefit analysis of gum removal might tend toward a net negative, especially in Britain’s current age of austerity, which is why I was charmed to see Ben Wilson’s gum paintings featured in The New York Times last month. Although he began his artistic career as a sculptor working mostly in wood, the Times reports that, for the past six years, Wilson has devoted himself to painting thousands of tiny pictures on the discarded, flattened gum blobs of London’s pavements:

He developed a technique in which he softens the gum with a blowtorch, sprays it with lacquer and then applies three coats of acrylic enamel. He uses tiny brushes, quick-drying his work with a lighter as he goes along, and then seals it with clear lacquer. Each painting takes between a few hours and a few days, and can last several years if the conditions are right.

IMAGE: Ben Wilson’s chewing gum art, via Flickr user Grahamc99.

IMAGE: A collection of Ben Wilson’s works, via Flickr user Judepics.

Some of his vibrant miniatures appear abstract, or purely decorative; others depict local landmarks or symbols; and still others broadcast personal messages in public: Wilson explains to the Times that he receives requests to commemorate births, deaths, young love, and even shop closings:

To mark the closing of a Woolworth’s a couple of years ago, Mr. Wilson crowded every employee’s name onto a piece of gum, along with a good-luck message from the managers. He painted another in which the employees thanked their customers. The two pictures are still there, even though the store is gone.

IMAGE: Yarn-bombing in Denver, spotted last weekend on my way to the MCA to judge cocktails.

IMAGE: My first sighting of yarn-bombing, on 14th Street between 2nd and 3rd, New York City, in autumn 2009.

Ben Wilson’s gum paintings reminded me irresistibly of another recent and lovely urban intervention: yarn bombing, in which guerrilla knitters decorate fly-posters with fuzzy frames, barbed wire with crocheted spiderwebs, and scaffolding pipes with striped cozies. In both cases, the application of individual artistry and craft to the functional décor of the contemporary urban landscape renders the invisible, visible, while tranforming the civic into the personal. As Wilson explains:

The only imagery that children see around them are billboards and TV; every part of their environment is out of bounds or sold off. That’s why they don’t care about their streets. This is a small way of connecting people.

IMAGE: A Ben Wilson streetscape on the street, via Flickr user Salimfadhley.

The appropriation of chewing gum litter in the creation of a distributed artwork that provides local colour, pride, and even memory is, in my opinion, the highest end to which a stick of Wrigley’s could ever aspire. After all, Ben Wilson’s paintings not only compel us to actually notice the reality of our gum-strewn streetscape, inviting us, like Primo Levi, to mine it for reflections on our culture’s habits and choices, they also inspire us to reconsider every aspect of the urban environment as an opportunity to add unexpected beauty.

What other overlooked possibilities do the otherwise unloved chain-link fences, steam stacks, and Jersey barriers of the modern metropolis offer?