As a coda to my previous post, I should note that before their adoption of apple ensachage and photographic tattoos, the nineteenth-century fruit growers of Montreuil had already adopted innovative peach growing techniques to produce the most coveted stone fruits in the world.

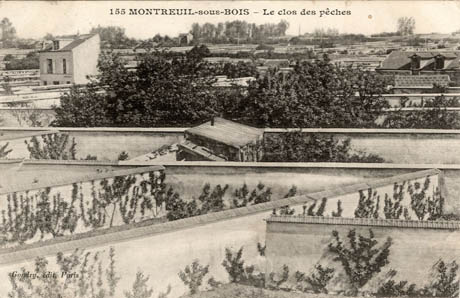

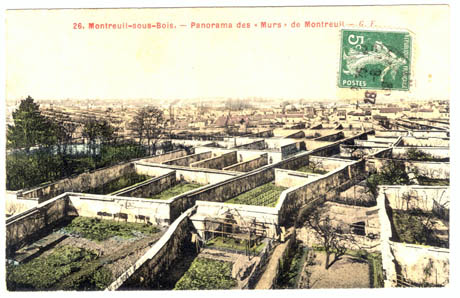

IMAGE: Postcards from the era show Montreuil’s seemingly infinite solar courtyards, Vues de Montreuil à la grande époque des Murs à pêches from the collection of the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil.

Their secret lay in the construction of a honeycomb of solar walls. As Suzanne Freidberg writes in Fresh, the Montreuillois enclosed rectangular plots “in walls of plaster — a material that absorbs heat much more effectively than brick — and oriented them all north-south, so as to capture the most sunlight.”

IMAGE: Vues de Montreuil à la grande époque des Murs à pêches from the collection of the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil.

This gridiron of sun traps were surprisingly effective, according to Freidberg:

Indeed, both day and night the gardens were warmer than their surroundings by several degrees Celsius. In this microclimate Mediterranean fruits thrived. Peaches ripened a month before others on the market, when prices were still sky-high. In addition, the villagers trained their espaliers to stretch out across the east-facing walls like giant fans cradling each peach in a perpetual sheltered sunbath. This design produced not only unusually big and beautiful fruits but also more of them from each tree.

IMAGE: Vues de Montreuil à la grande époque des Murs à pêches from the collection of the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil.

IMAGE: Harvesting Montreuil’s peaches — the best in France, and, some would argue, the world. From the collection of the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil.

French horticulturalists, unable to believe that illiterate peasants had come up with this system on their own, suspected they had stolen the idea from the king’s garden at Versailles. Nonetheless, observers marveled at the sight of solar walls applied at the scale of infrastructure, re-designing the landscape and microclimate of an entire village. Freidberg translates the comments of a contemporary visitor, Pierre Jean-Baptiste Legrand d’Aussy:

It’s a really interesting spectacle to look down from the surrounding hillsides on this immense multitude of gardens, carved up every which way by walls covered with trees and verdant vines. You think you’re looking at a hive of bees…

IMAGE: Vues de Montreuil à la grande époque des Murs à pêches from the collection of the Société Régionale d’Horticulture de Montreuil.

Looking at panoramic postcards of Montreuil from the end of the nineteenth century, with fully three-quarters of the town’s territory transformed into plaster-walled solar courtyards for peaches, it’s tempting to compare the landscape with the sea of greenhouses have similarly reformatted El Ejido, in the Almeira province of Spain, today.

IMAGE: El Ejido’s saladscape, via.

The desert landscape that previously served as the backdrop for Sergio Leone’s “spaghetti westerns,” as architect Keller Easterling notes in her chapter on El Ejido in Enduring Innocence: Global Architecture and Its Political Masquerades, is now a sea of plastic — the largest concentration of greenhouses in the world, hot-housing summer vegetables all winter long.

The nineteenth-century plaster wall of Montreuil is paralleled, in El Ejido, by the adaptation, in the 1970s, of a flat-roofed, “parallel type,” plastic-sheeting and wire structure used locally for growing table grapes. Just as in Montreuil, this single structural unit became the “germ,” in Easterling’s formulation, for a new landscape-scale agricultural infrastructure, reshaping the region’s ecology and its economy.

IMAGE: El Ejido from above, via.

IMAGE: Satellite imagery of the El Ejido peninsula, via.

Of course, the tiled suntraps of El Ejido have not only transformed a single town, but an entire peninsula — the 80,000 contiguous acres of parallel plastic greenhouses are clearly visible from space. In addition, while the fruit growers of Montreuil drew on their wives and children to provide cheap labour, the greenhouses of El Ejido rely on seasonal or illegal workers from North Africa, in a complicated and exploitative relationship that, as Easterling writes, has ignited a “tomato war” — “a translocal valve of labor, race, and migration problems in Europe.”

Unpacking the economic, ecological, and geopolitical forces that conspire to transform a “germ” into a highly engineered landscape, worthy of postcard and satellite photography, as well as our marveling attention — and then, as was the case in Montreuil and as seems inevitable in El Ejido, given its aquifer depletion, to dismantle it half a century later, is a fascinating exercise. The lucrative market in counter-seasonal produce has spurred ever more sophisticated architectures of climate modification — including, of course, my personal obsession, cold storage — marching across the urban hinterlands in formation…