The concept of terroir will be familiar to most Edible Geography readers; recently, we also explored the idea of “merroir,” or tasting place in sea salt. But what about aeroir—the atmospheric taste of place?

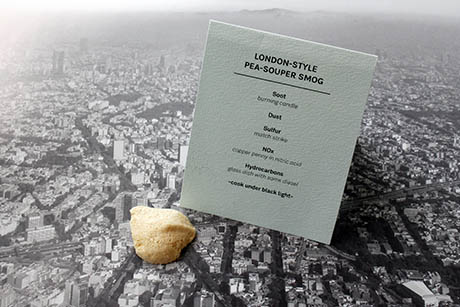

IMAGE: A London-style Peasouper Smog Meringue. Photo by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy.

This afternoon, the Center for Genomic Gastronomy and I will be offering New Yorkers a chance to taste aeroir, with a side-by-side tasting of air from different cities. With the support of the Finnish Cultural Institute in New York, we have spent the past few months designing and fabricating a smog-tasting cart, complete with built-in smog chamber, as well as developing a range of synthetic smog recipes.

Having made its debut at a meeting of the World Health Organization in Geneva a fortnight ago, the cart will be stationed on Rivington Street, just off the Bowery, from noon to six today. We will be serving up free smog meringues from three different locations as part of the New Museum’s IDEAS CITY street festival.

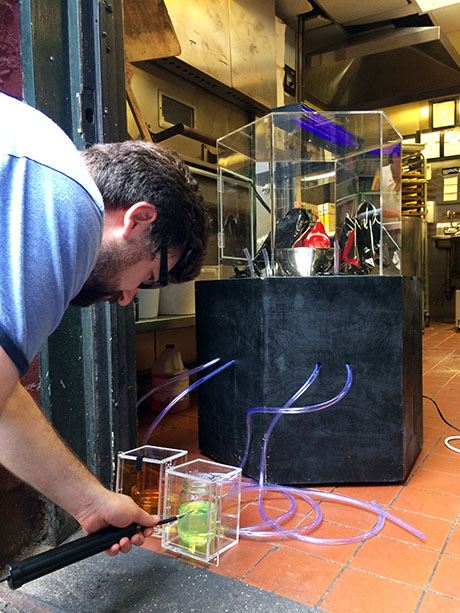

The cart builds on an earlier project by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy. In 2011, after reading that an egg foam is ninety-percent air in Harold McGee’s bible of culinary chemistry, On Food and Cooking, the Center took whisks, mixing bowls, and egg whites out onto the streets of Bangalore, using the structural properties of meringue batter to harvest air pollution in order to taste and compare smog from different locations around the city.

IMAGE: Harvesting urban air pollution using egg foams. Photo by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy.

I’ve been a fan of the Center’s work for a while (I included their publication, Food Phreaking #001, in my best books list for 2013), and, inspired by their smog meringue project, I began to speculate about the concept of “aeroir,” and the idea that urban atmospheres capture a unique taste of place.

As we started to work together, I visited the atmospheric process chambers at the Bourns College of Engineering, at the University of California, Riverside, to see how scientists actually recreate smog conditions in the lab, in order to study the relationship between emissions and atmospheric chemistry.

IMAGE: Mobile smog chamber, UC Riverside CE-CERT. Rows of UV lights are used to “bake” the smog. Photo by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: Deflated Teflon bags hand in the large atmospheric emissions chamber room at UC Riverside CE-CERT. The mirrored walls reflect UV light to ensure the smog “bakes” evenly. Photo by Nicola Twilley.

During my visit, a group of students was setting up an agricultural smog, which is characterised by ammonia and amines from feedlot manure lagoons and other organic waste. These combine with NOx and incompletely combusted hydrocarbon emissions from cars, power plants, and industry to give the Central Valley of California, for example, some of the worst air quality in America.

We watched as a team injected precise amounts of different precursor chemicals into a gigantic Teflon chamber, where they would be cooked under hundreds of UV lights in order to catalyse the reactions that create smog. The students were hoping to characterise those reactions, in order to understand the entire chain of chemical processes leading to smog formation, and then design and test ways to prevent or mitigate against it.

With advice from Professor David Cocker and Mary Kacarab at UC Riverside, the Center for Genomic Gastronomy and I worked out how to build a DIY, mini-smog chamber. We then developed and tested recipes using readily available precursor ingredients in create a variety of different smogs.

IMAGE: Smog tasting cart set up in Geneva, at a meeting of the World Health Organisation. Photo by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy.

IMAGE: Emissions from these precursor chemicals are pumped into the cart’s chamber and exposed to UV light to create a synthetic smog. In this image, pine needs and orange peel provide terpenes to simulate a biogenic smog. Photo by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy.

After running around New York City in order to source our precursor ingredients (a huge thanks to Kent Kirshenbaum, chemistry professor at NYU and co-founder of the Experimental Cuisine Collective), we spent Thursday afternoon and evening in the kitchens of Baz Bagel (excellent bagels, amazing ramp cream cheese, and truly lovely people) assembling the cart, mixing different chemical precursors, and then “baking” them under UV light to form a London peasouper, a 1950s Los Angeles photochemical smog, and a present-day air-quality event in Atlanta.

We chose these three places and times to showcase three of the classic “types” that atmospheric scientists use to characterize smogs: 1950s London was a sulfur- and particulate-heavy fog, whereas 1950s Los Angeles was a photochemical smog created by the reactions between sunlight, NOx, and partially combusted hydrocarbons. Present-day Beijing often experiences London-style atmospheric conditions, whereas Mexico City’s smog is in the Angeleno style.

IMAGE: Diesel and NOx, two precursor chemicals. Photo by Nicola Twilley.

Meanwhile, at its worst, Atlanta’s atmosphere is similar in composition to that of Los Angeles, but with the addition of biogenic emissions. An estimated ten percent of emissions in Atlanta are from a class of chemicals known as terpenes, from organic sources such as pine trees and decaying green matter. We had also hoped to create a Central Valley smog as well, but time got the better of us.

Each city’s different precursor emissions and weather conditions produce a different kind of smog, with distinct chemical characteristics—and a unique flavour.

IMAGE: Whisking meringues inside the smog chamber at Baz Bagel on Thursday. The long gloves were sourced at a sex shop, hence the fetching black vinyl. Photo by Gabe Harp.

As it turns out, Arie Haagen-Smit, the man known as the “father” of air pollution science, was originally a flavour chemist who rose to prominence thanks to his work on pineapples. Nadia Berenstein, the flavour historian I interviewed for a recent episode of Gastropod, pointed me to a speech Haagen-Smit gave in the 1950s, explaining his shift in research from fruit flavours to smog science to a room full of his former colleagues. In it, he explains, “I am engaged at the present time on a super flavor problem—the flavor of Los Angeles.”

I can confirm, based on Thursday night’s bake-off, that the different cities’ smogs do, indeed, taste different (and yet equally disgusting).

IMAGE: Gabe Harp piping “London” mini-meringues in the kitchen at Baz Bagel. Photo by Nicola Twilley.

Inhaling smog over extended periods is extremely damaging to human health. In New York City, which has the 12th worst ozone levels in the nation according to the American Lung Association’s Annual “State of the Air” report, air pollution levels are highest in neighborhoods that are majority non-white and low-income—a particularly insidious form of environmental injustice. By transforming the largely unconscious process of breathing to the conscious act of eating, the smog-tasting cart aims to create a visceral, thought-provoking interaction with the air all around us.

One of my collaborators, Zack Denfeld of the Center for Genomic Gastronomy, reports that during previous installations and performances of the Center for Genomic Gastronomy’s Smog Tasting project, the most frequently asked question has been: “Is this safe to eat?” His typical response is, “Well, is it safe to breathe?”

Unsurprisingly, there is not a lot of research on the impact of eating polluted air, as opposed to the more common method of exposure, breathing it. However, the scientists we have spoken to have pointed out that the human digestive system is more robust and better able to deal with these chemicals than our respiratory system—and that the trace amounts captured in a mini-meringue make for a very small dose, in any case.

IMAGE: Zack Denfeld pumping precursor emissions into the smog chamber. We didn’t assemble the entire cart at Baz Bagel, due to space constraints. Photo by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: Smog “baking” in the chamber at Baz Bagel. Photo by Nicola Twilley.

In any case, our hope is that the meringues will serve as a kind of “Trojan treat,” creating a visceral experience of disgust and fear that prompts a much larger conversation about the aesthetics and politics of urban air pollution, as well as its health and environmental effects. Eat at your own risk!

This smog-tasting cart is intended as the start of a larger collaboration exploring the concept of “aeroir.” After all, air is the site at which we have an intimate, constant interaction with a geographically specific manifestation of urban planning, economic activity, environmental regulation, and meteorological forces. We hope to develop a multi-sensory series of installations, devices, and performances to make that interaction sense-able.

For example, we imagine that air quality could function as a kind of culinary constraint that inspires new kinds of regional cuisine, aided by the development of smog flavour wheels. Working with scientists who are measuring how smog affects the human sense of smell, as well as chefs, we could imagine developing a menu of street food pairings for particular atmospheric conditions.

Equally, we hope to partner with engineering labs to create novel wearable technologies that add olfactory and trigeminal stimulation to any eating experience—a sort of “smog seasoning.” Aeroir may well be the missing ingredient that makes tacos taste the same in the restaurant back home as they did on the streets of D.F.

The overlap between culinary technology and atmospheric conditions is literal as well as metaphorical. During my visit to UC Riverside, I visited their new Cooking Emissions Laboratory at UC Riverside to explore new research into the impact of “burger smog” on urban air quality—something I will be reporting on at greater length in the coming weeks.

IMAGE: Atlanta-style smog meringues as served in Geneva. Photo by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy.

With their original smog meringue insight, the Center for Genomic Gastronomy opened up a powerful method to translate quantitative environmental data and the scientific understanding of pollution and physiology using the images, metaphors, and tools of food and cuisine. It’s a thrill to work with them to explore its potential.

The smog-tasting cart will be serving smog meringues on Rivington Street between Bowery and Chrystie from noon today until 6 p.m. (or whenever supplies run out), as part of the New Museum’s IDEAS CITY street festival, directed by the legendary Joseph Grima. Our participation is made possible thanks to the support of the Finnish Cultural Institute in New York, as part of their 25th Anniversary program, which focuses on the theme of urban nature. Scott Wiener, pizza tour leader extraordinaire, connected us to Baz Bagel, who let us use their kitchen when the day’s bagel rolling, boiling, and baking was done. Scientists David Cocker, Mary Kacarab, Kent Kirshenbaum, and Darby Jack have been all been exceedingly generous with their time and expertise as well as very tolerant of our weird approach to their field of research. As always, thanks also to Geoff Manaugh, who accompanied me on my visit to UC Riverside and helped discuss the concept of aeroir.