While I was writing about Scandybars yesterday, I kept thinking that I had read something interesting about the relationship between sandwiches and the architectural cross section not too long ago. As usual, my prematurely senescent memory refused to offer up any more information, but then, as I packed up boxes of books in preparation for what feels like my millionth move, I picked up my copy of Sandwich, a supplement to the Fall 2010 issue of Meatpaper.

Nestled between an interview with the 11th Earl of Sandwich (the 4th Earl is credited with popularising the consumption of meat between bread) and a meditation on why Thom Yorke would wait with a pack of sandwiches as well as a gun in the Radiohead song, “Talk Show Host,” is an essay by architect Nicholas de Monchaux, whose recent book, Spacesuit, is one of the best things I’ve read this year.

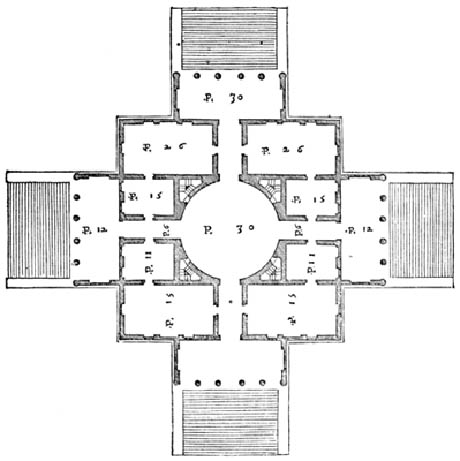

IMAGE: Palladio’s Villa Rotonda in section, via.

IMAGE: Palladio’s Villa Rotonda in section.

In his essay, de Monchaux discusses art historian Rudolf Wittkower’s suggestion that the idealised proportions of Renaissance buildings such as Palladio’s Villa Rotonda can only be understood through the section — a vertical cut that “reveals a precisely perfected layering of space and substance that was contained by what might seem to have been an overwhelming or inscrutable façade.” Drawing on philosopher Mircea Eliade’s The Sacred and the Profane, de Monchaux then suggests that while plan view is inherently mundane and grounded (from planum, or the bottom of the foot), the section reveals the divine harmony of vertical space.

IMAGE: Egg salad and turkey avocado BLT sandwiches from Pret A Manger, photo by my favourite chroniclers of lunch, Front Studio.

Extrapolating from Renaissance churches to the shelves of Pret A Manger, de Monchaux suggests that the “secret truth of the sandwich is revealed on its sectioning”:

[Leon Battista] Alberti’s reflection on perfect proportion in building equally applies to the perfect sandwich, which will “awake sublime sensations … in such a way that every part has its absolutely fixed size … and nothing could be added or taken away without destroying the harmony of the whole.”

“And,” de Monchaux concludes, “it is only through the cut that this mystery is revealed.”