London’s wholesale food markets are of such venerable antiquity that New Spitalfields, a fruit and vegetable market that “started life in the thirteenth century in a field next to St Mary Spittel on the edge of the Square Mile,” can be casually described as “one of the City’s younger markets.”

IMAGE: Traders at New Spitalfields Market, from BBC Two’s Markets series.

Things have changed, however, since the days when every joint of beef, fillet of plaice, potato for the accompanying chips, and any other perishable foods on Londoners’ plates would have passed through New Spitalfields and its elder siblings on its way from farm to table. As food producers and food vendors have grown, and industrial growers increasingly deal directly with Sainsbury’s, the role of the wholesale market in the middle has shrunk.

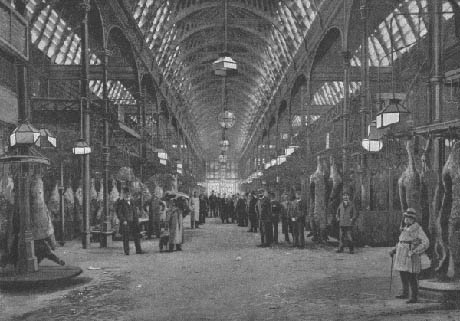

IMAGE: Smithfield meat market, as depicted in The Queen’s London: a Pictorial and Descriptive Record of the Streets, Buildings, Parks and Scenery of the Great Metropolis, 1896, via.

IMAGE: Smithfield Market today, via the Association of London Markets.

This summer, BBC Two produced an excellent mini-series of three hour-long documentaries looking at the ways in which traders at New Spitalfields, Billingsgate fish market, and Smithfield meat market have adapted — or not — to changes in London’s foodscape.

Despite the fact that each of the markets has experienced a steep decline in the volume of food that passes through its gates — a 2002 report by the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs estimated that, within the past decade, the tonnage of fish sold at Billingsgate had shrunk by approximately fifteen percent, and the tonnage of meat at Smithfield was down by an even more significant twenty-six percent — I was surprised to learn how large a role they still play in London’s food supply.

IMAGE: Billingsgate market, photograph by Hema.

The food that Londoners eat at home does indeed come, for the most part, from supermarkets, but the wholesale markets still account for twenty percent of the city’s food supply, with brokers up before dawn each day to buy fresh fish, meat, fruit, and vegetables for hotels, restaurants, pubs, schools, street market stalls, and even prisons. Like all good markets, London’s wholesale markets are still vast, busy, and slightly overwhelming, filled with an extraordinary diversity of both people and produce, colourful language and arcane ritual, and a sense of controlled chaos.

Billingsgate, the first wholesale market profiled in the BBC series, seemed to be the most optimistic of the three, despite the fact that it was recommended for closure in the 2002 DEFRA report and, at the time the BBC was filming, was grappling with a controversial plan to change its historic bylaws to allow fish to be carried by anyone, rather than the traditional licensed porters.

IMAGE: Billingsgate fish market, via the blog of the former Master Draper of the Worshipful Company of Drapers of London.

Traditionally, the fish porters had a job for life — and one that, for many, had been handed down several generations: as the BBC’s narrator intoned above images of a white-coated army pushing trolleys piled high with styrofoam boxes, “Men like this have been moving fish since Elizabethan times.” Or, as Geoff, who had been portering alongside his father for eighteen years, said, “I’d’ve got less for murder.”

IMAGE: Billingsgate fish market, from BBC Two’s Markets series.

Although trading at the market starts at 2am, fish cannot be moved until the bell sounds at 5am, at which point the porters cover up to thirteen miles in just a few hours, receiving a fixed retainer and supplemental “bobbin” payments based on the amount of fish they carry. The term “bobbin,” the BBC explained, refers to the particular leather hats that porters used to wear to carry the fish on their heads, which featured a deep brim to catch the run-off from the wooden crates.

IMAGE: Billingsgate fish market, from BBC Two’s Markets series.

Meanwhile, inside the market’s deep-freeze — Britain’s largest — the men work in pairs in case one develops hypothermia. Outside, cart minders work for tips and cups of tea, guarding customers’ purchases until they can be moved.

The humour and haggling skills on display were remarkable: Roger Barton, who has sold fish at the market for fifty-one years, compared pollock to someone “sitting at home in a tracksuit watching Jeremy Kyle and eating a burger,” and dismissed a supplier’s excuses briskly, noting that “when they were coming over from Dunkirk, they never worried about the weather.”

IMAGE: Roger Barton with two of his employees at Billingsgate fish market, from BBC Two’s Markets series.

However, we also learned that Billingsgate has just a few women in its 300-strong workforce, and that, today, up to seventy percent of its customer base is Chinese. “If it wasn’t for them, it wouldn’t be worth opening,” according to Barton.

IMAGE: Queer gear at New Spitalfields market, from BBC Two’s Markets series.

These themes recurred at Smithfield and New Spitalfields, the second and third markets in the BBC series. At New Spitalfields, Kevin, an exotic fruit expert, surveyed his array of rambutans and pitayas, noting that “years ago, they used to call it queer gear, but it’s all everyday stuff now.” Meanwhile, after a lifetime in the celery trade, Bill had decided to sell his stall to Polish mushroom importers rather than try to adapt to Britons’ changing tastes.

IMAGE: A vintage celery poster left on the wall by the departing stall owner, from BBC Two’s Markets series.

At Smithfield, too, everyone acknowledged the importance of “the Muslims and the ethnics” who made up the majority of their customers, but the market seemed to be stuck in a time warp (or, in the words of one trader, “an oasis from the PC world outside”), with men sharing naked cell phone photos amidst racist banter.

The BBC followed Dee, a single mum who was the first woman to try working the 2 to 8am shift among the meat-cutters at the back. By the end of an hour of gripping TV that included a horrifying initiation ceremony involving blood, eggs, and offal, she’d given up. Her boss, asked about the harassment, shrugged and admitted, “That’s Smithfield market, unfortunately.”

IMAGE: Biffo, one of the Smithfield meat market’s colourful characters, from BBC Two’s Markets series.

Given the anachronisms and pervasive sense of faded glory, it was hard not to fear for the markets’ continued survival. However, this wouldn’t be the first time London’s markets have been prematurely condemned.

A quick look at George Dodd’s The Food of London, a survey of the means by which the city was fed in 1856, is instructive: barely a sentence after noting that “SMITHFIELD will ever remain a great landmark in the history of London,” he describes “its decline and fall,” detailing “complaints against Smithfield as a spot unsuitable for a cattle-market” and the alleged “roguery of the cutting-butchers,” while still marveling at the “exciting and even savagely picturesque” nature of the proceedings.

IMAGE: Exterior of New Spitalfields market after trading is finished for the day, from BBC Two’s Markets series.

Ultimately, the 2002 DEFRA report recommended that Smithfield and Billingsgate be closed, and the now-valuable land “be released for alternative uses.” Meanwhile, the report concluded that, as “catering has become the engine of the London markets,” the remaining wholesale markets (New Spitalfields, New Covent Garden, and Western International) should abandon their specialities to serve as one-stop shops for the hospitality trade:

Caterers will increasingly seek to improve their efficiency and that means that consolidation of supplies will need to take place at some stage earlier in the supply chain than their kitchens. They will seek to collect their supplies from sites that offer a full product range or require their supplies be delivered in consolidated loads. […] It is recommended that London should be serviced by three composite markets for meat, fish, fruit and vegetables based at the sites of Nine Elms, Spitalfields and Western International.

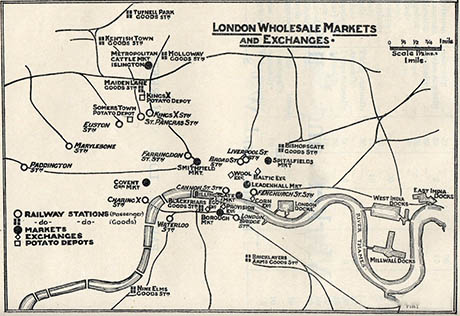

IMAGE: London’s wholesale markets, potato depots, and exchanges in 1930, from Markets and Fairs of England and Wales Part VI, London, by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, HMSO, London, 1930, via. Billingsgate is obscured at the bottom right, and Spitalfields is still in its former, more central location, as is Covent Garden.

This conclusion seems reasonable, but also short-sighted. First of all, it diminishes the markets’ role in price formation, by which I mean the way that Billingsgate, for example, allows a large enough proportion of the city’s supply and demand for different kinds of seafood to converge to establish a “fair” price (at least in market terms).

The BBC focused on the exotic fruits and Kosher meats increasingly demanded by the markets’ customers, which, I think, points to a more promising future direction for specialised markets that can concentrate small-scale production and catering custom to create economies of scale.

IMAGE: Artisanal pickles, via.

In a foodscape that seems increasingly hospitable to boutique producers and niche markets (as evidenced by the rash of artisanal pickles, gluten-free goods, and goat milk desserts for sale in London), what if New Spitalfields took the lead in sourcing wild-foraged foods, heirloom varietals, and artisanal chutneys, alongside its sacks of potatoes, apples, and onions?

This would certainly help small-scale producers reach new markets, but restaurants, catering companies, and ethnic shops would surely also appreciate the convenience and added value of being able to offer their customers unusual or regional specialities in reasonable quantities, without the hassle of tracking them down themselves.

As an example, in the New York City region, mid-size farmers are currently arguing that Hunt’s Point, the city’s wholesale market, should use its forthcoming renovation to begin aggregating regional produce, which would help New York State apples achieve the distribution and economies of scale required to become as common in New York City’s grocery stores as apples from Washington State or New Zealand.

IMAGE: Susan Ho’s company, Tea Aura Inc., developed its tea-infused cookie business at the Toronto Food Business Incubator, a city initiative run by Foodprint Toronto panelist Michael Wolfson. Photo by Brett Gundlock/National Post.

Meanwhile, the advantages of having inspectors, waste disposal, and even shared frozen storage on a single site could be extended to the markets’ future customers: why not build culinary incubators nearby, so that catering start-ups benefit from proximity to vendors as well as shared commercial kitchen facilities?

IMAGE: Billingsgate Fish Market: Delivery Vehicles in Lower Thames Street (1930), from Markets and Fairs of England and Wales Part VI, London, by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, HMSO, London, 1930, via.

Issues of transport and access are more complicated, but, certainly, larger composite markets are not a problem-free solution, as the high rates of asthma in the Hunts Point neighbourhood of the Bronx demonstrate.

The BBC documentaries showed that, increasingly, buyers are purchasing by phone rather than coming in everyday in person; perhaps some investment in infrastructure to combine deliveries, build a robust online or phone business, and improve transit or even build part-time “food lanes” (like the city’s recent dedicated Olympic lanes) between the wholesale markets, as well as to the city centre, could help solve the most pressing challenges.

Of course, these are just ideas — they need plenty of research and data to become anything more useful than that, not to mention significant investment to implement. Still, London’s wholesale markets are too important — in terms of their heritage and people, certainly, but also because of their current and future role in feeding the city — to be allowed to fall away in favour of Sysco.

NOTE: I’m looking forward to exploring the topic of market cities in much more depth at the fantastic-sounding 8th International Public Markets Conference in Cleveland, Ohio, on September 21-23, which I will be attending as a guest of its organisers, the Project for Public Spaces, and the local visitors bureau, Positively Cleveland. You can register to attend here, as well as expect reports on the proceedings (and perhaps better informed ideas!) from me here.

Previously on Edible Geography: The Axis of Food.