IMAGE: Memory Lane, courtesy Grove Care, Ltd.

Among the facilities at the Blossom Fields care home near Bristol is “Memory Lane”: a reconstructed 1950s street where residents, many of whom suffer from Alzheimer’s or dementia, can mail letters in a George VI Post Box, make calls from a restored phone box, enjoy a pint (or, more often than not, a cup of tea) in the White Horse Inn, or pop into the greengrocers for some shopping.

Blossom Field’s Memory Lane is perhaps the most elaborate example of an increasingly popular technique in dementia care: retro-decorating.

As The Guardian explained, in an article about Surrey county council’s efforts to decorate old people’s homes with period advertisements for Bisto gravy granules and Tunnock’s Caramel Wafers, people with dementia often suffer from short-term memory loss, making the distant past seem more familiar and reassuring than the forgotten present. In response, “retro-decorating schemes see modern technologies replaced by older versions, surrounding dementia sufferers with objects from the past to trigger their memory, and using colour and light to make daily tasks simpler.”

Over the past few years, care homes across the UK have thus begun snapping up Bush transistor radios and bakelite phones at car boot sales and on eBay, as well as putting out a call for members of the public to donate mahogany furniture, posters, and “tea sets, fruit bowls, and ornaments” from the 1950s and 60s.

IMAGE: A resident looks through the greengrocer’s window. Photograph via.

Blossom Field’s Memory Lane has taken the trend one step further, however, with the construction of an entire “reminiscence village.” In addition to offering a comfortingly familiar environment filled with memory triggers, Memory Lane is also designed to manage what the Alzheimer’s Society refers to as a common compulsion among sufferers to walk about. As Christopher Taylor, the home’s senior manager, explained, “People with dementia wander. We want to give a purpose to their movement. It provides a destination.”

The shops and pub in Memory Lane are not intended as accurate historical reconstructions (the pub, for starters, would require a thick fug of cigarette smoke to achieve olfactory authenticity), but rather as stage sets for the involuntary performance of memory.

However, the most interesting aspect of Memory Lane, at least for Edible Geographers, is the centrality of food and drink.

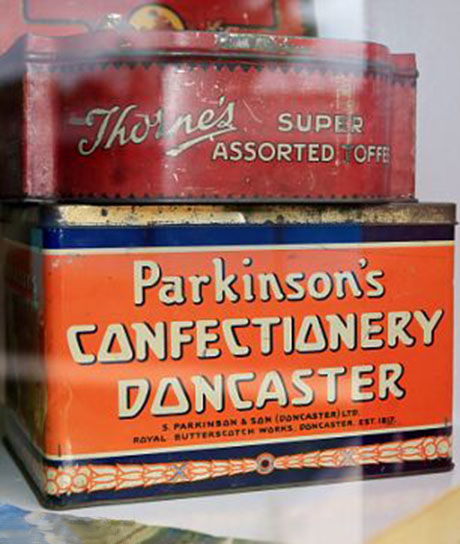

IMAGE: Tins of sweets in the greengrocer’s. Photograph via.

Two out of the three simulated environments — the pub and greengrocer’s — sell food and drink directly, while the Post Office features a display of ration books, a pamphlet of near-Biblical significance to anyone trying to feed a family in U.K. during the 1940s and 1950s.

Indeed, I first heard of Memory Lane during an episode of The Food Programme on BBC Radio 4, in which host Sheila Dillon and nutritionist Clare Millar — who is trying to promote a return to wartime food habits — sat down to talk with elderly residents Pat and Anna about their own, quite vivid memories of eating in post-war Britain.

IMAGE: Ration books on display in the Post Office. Photograph via.

From Pat and Anne’s reminiscences, as well as descriptions of Memory Lane in the British media, it seems evident that residents really do find that these small activities — weighing fruit on the old-fashioned greengrocer’s scales, buying tuppence-worth of toffee from a tin, or setting a pint down on a vintage beer mat (an increasingly endangered species itself) — prompt a much larger recall. One 86-year-old former engineer was particularly taken with a tin of Nuttall’s Mintoes, explaining to a Telegraph journalist that his mother used to run a sweet shop: “We sold ice cream and Everton toffees. […] It’s good to have your memory jogged. Once one thing comes back, then other things follow.”

Fascinatingly, the bananas hanging in the greengrocer’s window have proven to be a particular point of conversation. “For most of our patients they were a rarity [when they were young],” manager Christopher Taylor told The Telegraph. “People are talking about how they’d share one banana between the whole family.”

The time-machine properties of food smells, made famous by Proust’s madeleine, have recently been shown by scientists to have potential in treating dementia. Indeed, last year, fragrance and flavouring company Givaudan began trialling its custom-blended “Smell a Memory” kits, including the scent of “Mom’s Home Cooking,” with hospital-bound dementia patients in Singapore.

IMAGE: Givaudan’s “Smell a Memory” kit: vials of meaningful smells, custom-blended in collaboration with residents of a Singapore nursing home. Photograph via.

But, as Blossom Hill’s Memory Lane demonstrates, the larger food environment is equally rich in triggers, many of which vanish from society without notice, but could very well hold the key to deeply embedded memories. I can only imagine what hearing the particular bleep of a bar-code scanner or the clatter of a thermal receipt printer will invoke, in my old age. And will the Memory Lane of 2060 feature a Starbucks and a Tesco?