My new favourite art prize is the Szpilman Award, which exists to promote “such works whose forms consist of ephemeral situations.”

The idea of canonising art whose very nature is fleeting is compelling, in a quixotic kind of way. Meanwhile, the works themselves are understated and charming, yet illustrate the seemingly infinite potential to see the world slightly askew that is offered to each of us afresh every moment.

IMAGE: 2010 winner, Treebute to Yogya, by Sara Nuytemans and Arya Pandjalu, took the form of a performance in which a bike gang drove through the city of Yogyakarta wearing helmets filled with soil and planted with a tree.

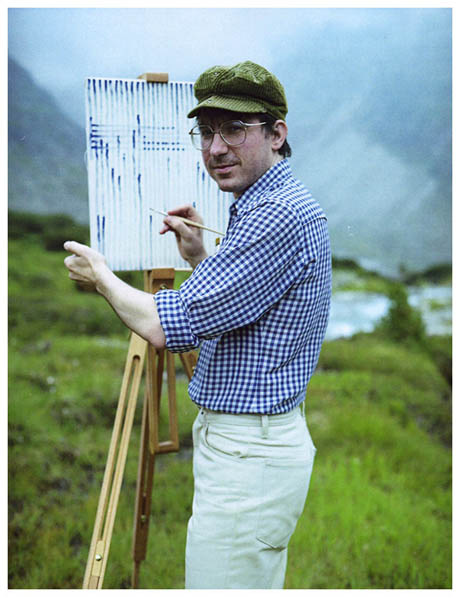

IMAGE: 2009 winner In den Zilltertaler Alpen, in which the artist Hank Schmidt in der Beek “stands in the manner of a plein air painter surrounded by mountain scenery and paints the pattern of his shirt on canvas.” Photo by Fabian Schubert.

IMAGE: Berndnaut Smilde, Nimbus, “a wonderful and well-composed cloud in a room” and a 2010 finalist.

This year’s winner, Slovakian artist Jaroslav Kyša, was recognised for his urban intervention, The Barrier, which used food to form a flock of pigeons into a temporary, living barrier in front of a branch of Primark, in London.

As Americans gear up for the annual Black Friday festival of shopping that has all but overshadowed turkey and pumpkin pie as the central focus of the Thanksgiving holiday, there is something wonderfully unsettling about watching London’s bargain-hunters have to force their way through an equally single-minded, jostling mass of winged vermin.

IMAGE: Jaroslav Kyša, The Barrier

Kyša’s work reminded me of Robert Sullivan’s excellent book, Rats, which examines another of the city’s least welcome inhabitants as man’s “mirror species” — a parallel universe through which to understand those aspects of human nature, history, and urban environments that are more comfortably overlooked.

City rats live on rubbish — the food we discard — and thus their habitats form a kind of inverted guide to the city’s edible landscape: a map of all the food we don’t eat. According to Sullivan,

Some of the health department rodent-control field-workers say that a severe rat infestation depends on at least one good chicken place in a neighbourhood; people buy chicken, take it out, and leave trails of chewed wings and bits of breasts.

Indeed, although people commonly believe the entire subway system is full of rats, Sullivan is at pains to point out that “rats are not everywhere in the system; they live in subways according to the supply of discarded human food and sewer leaks.” Sewers themselves, the final loop in the city’s digestive system, helped today’s ubiquitous brown rat colonise the city — before their development, brown rats preferred to live in burrows on farms.

IMAGE: Sewer rats!

In his chapter titled “Food,” Sullivan describes the pioneering work of Martin W. Schein, who was the first to scientifically show a positive correlation between the number of rats and the amount of garbage, using Baltimore as a test case. Schein apparently hoped “one day to be able to predict the number of rats in an area from pounds of refuse,” but moved onto studying turkeys before achieving this goal.

However, his findings did include a list of rat dietary preferences and dislikes. Under the heading “Garbage Rats Liked,” we find scrambled eggs, macaroni and cheese, corned beef hash, fried chicken, and white bread — all currently enjoying a renaissance due to the popularity of nursery-nostalgic comfort food. Conversely, “Garbage Rats Didn’t Like As Much” could just as easily describe the contents of a salad bar: beets, celery, cauliflower, cabbage, and carrots.

IMAGE: Rat buffet.

In a fascinating side-note, post-Schein studies have shown that rats also develop a “local food dialect,” or an appreciation of the ethnic foods of the neighbourhood in which they live. For example, though Schein reported that rats preferred sweet to spicy foods, an exterminator in East Harlem told Sullivan that “the rats there have learned to enjoy spicy garbage.”

The larger point, however, is that food — its consumption, excretion, and disposal within the city — has, unintentionally, for the most part, shaped the urban pestscape. As exterminator mogul Barry Beck tells Sullivan, “They design buildings to support pigeons and for infiltration by rodents because they don’t think about it.”

IMAGE: Jaroslav Kyša, The Barrier

Beck dreams of a day when he will be brought in at the planning stage, to analyse weaknesses and “build out pests without pesticides.” Meanwhile, Jaroslav Kyša’s Barrier is a more tangible reminder that food is a powerful force for cross-species urban design — but, also, that the unwanted animals that live alongside us have much to tell us about our cities and ourselves.