Dutch artist Esther Polak spent frustrating years in art school trying to depict pastoral landscapes: dragging an easel out into the meadows near where she grew up; experimenting with oil paints, pastels, and photography. The results, as she tells it (at the ElectroSmog International Festival for Sustainable Immobility in March) were unsatisfactory.

IMAGE: Dutch dairyscapes, (left) Jacob van Ruisdael, View over Harlem, (right) Vermeer, The Milkmaid.

Part of the problem, she explains, is that “most of this part of The Netherlands looks like a green meadow — but, actually, you’re looking at a landscape of milk production.”

Then one day, some friends took Polak out on a boat that was equipped with GPS. She decided to experiment with the technology, equipping volunteers with PDAs back in 2002, before ubiquitous mobile computing, in order to produce user-portraits of Amsterdam. With a sense of the technology’s potential, she then returned to her original obsession: figuring out how to depict the landscape in a way that also revealed the industrial and agricultural processes that gave it shape.

IMAGE: NomadicMILK installation.

NomadicMILK, Polak’s most recent work, is currently on display as part of an exhibition called Whose Map Is It?, at the Institute for International Visual Arts in London. In it, she “tracks the daily routes of two milk related economies in Nigeria”: the routes of the Fulani, “nomadic herdsmen who move with their cattle in annual migrations in search of water, fodder and markets”; and the distribution networks of PEAK milk, a Dutch company whose condensed milk cans and milk powder sachets are “available on every street corner in Nigeria.”

IMAGE: Peak Milk products on shelves in Nigeria (photo from Polak’s blog).

IMAGE: Mr. Idiris and his family (photo from Polak’s blog).

Between January and December 2009, Polak spent months in Nigeria, recruiting a herdsman, Mr. Idiris, as well his most cooperative cow, Purdy, and his sister-in-law, Binta, who travels to local markets to sell nonno, a yogurt drink made from the milk Mr. Idiris collects.

IMAGE: Binta, Mr. Idiris’s nonno-producing and vending sister-in-law (photo from Polak’s blog).

IMAGE: Purdy, the chosen cow (photo from Polak’s blog).

She also signed up Audu, a truck driver who transports imported milk solids from Lagos harbour to the Peak milk factory, and Usman, whose lorry carries Peak milk from the factory to a distribution centre in Abuja, and then to shops and supermarkets in the Kubwa suburb of the city.

IMAGE: Milk products arrive at Lagos harbour (much of the supply is shipped from The Netherlands) (photo from Polak’s blog).

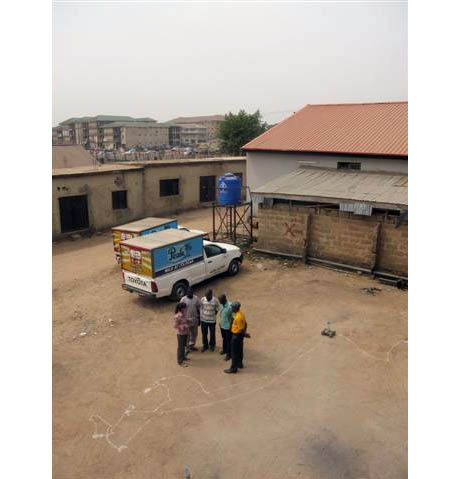

IMAGE: Polak with a Peak milk truck (photo from Polak’s blog).

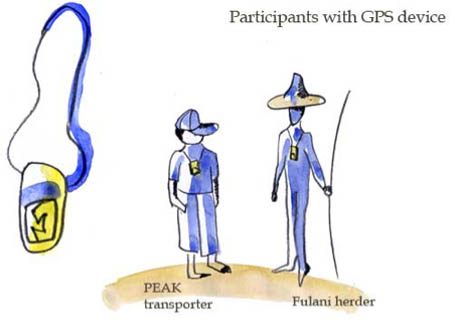

Each participant — including the cow — wore a GPS transponder as they went about their journeys, which recorded Mr. Idiris’s migration between the dry season and wet season pasturage, as well the shorter daily paths of one day’s herding or a Peak milk delivery round.

IMAGE: From Polak’s sketchbook.

Cumulatively, these traces map the path of two different dairy economies through the Nigerian landscape, as a result of the individual mobility of each actor in milk’s journey.

They intersect just once, when Usman’s delivery route supplies Peak milk to a shop directly opposite the spot where Binta typically ends her distribution round, selling the nonno that she makes from the milk Mr. Idiris’ cows produce.

IMAGE: Mr. Idiris’ herding movements plotted on the same sheet as Usman’s route bringing Peak milk from the harbour at Lagos to the distribution centre in Abuja (from Polak’s final monoprint series, for sale here).

There is something quite amazing about layering the logic of nomadic herding routes, based on inherited traditions, annual and daily climatic variations, and the mobility of indigenous livestock, onto the same landscape as the more recently developed patterns of international shipping, truck transportation, and supermarket inventory control. As Polak notes, “No matter how different their lifestyles might seem, the two groups can be considered colleagues in a shared workplace.”

IMAGE: Binta’s walk to market overlaid onto Audu and Usman’s separate truck drives from the harbour to the Peak milk factory, and Usman’s distribution round in Kubwa, Abuja (from Polak’s final monoprint series, for sale here).

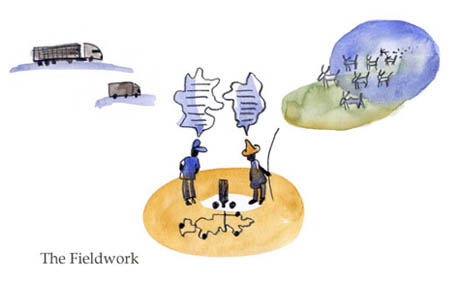

Rather than simply presenting these maps, however, Polak’s project revolves around the way each person involved in this greater milk journey understands their own movement within it.

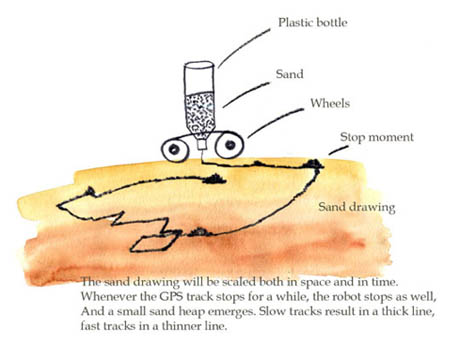

To that end, she spliced together a toy robot on wheels and a plastic bottle filled with locally-gathered white sand, in order to create an ingenious Heath Robinson-eque device that redraws each journey exactly as it happened, albeit at a much reduced scale and a speeded-up timeframe.

IMAGE: The sand-drawing robot, from Polak’s sketchbook.

IMAGE: Narrating their routes, from Polak’s sketchbook.

After Polak received the GPS unit back from each participant, she invited them to their narrate their route as the robot slowly translated the data into uneven lines of sand on the ground. Her final installation combined those narratives, in the form of video-recordings, displayed alongside robot-created prints of the tracks:

The robot is used to draw the sand tracks over pieces of canvas, in exactly the same way as it was done during the workshops in Nigeria. After the sand drawings are finished, graffiti spray-paint is used to color the background. A couple of hours of drying makes it possible to remove the sand with a soft piece of cloth. This reveals a razor-sharp white image of the tracks where every grain of sand stands out as a white and uniquely placed pixel.

IMAGE: Binta’s route, solo (from Polak’s final monoprint series, for sale here).

IMAGE: Robot with plastic bottle of sand (photo from Polak’s blog).

IMAGE: Polak with the sand-drawing robot (photo from Polak’s blog).

Despite my unending enthusiasm for maps, the video-narratives (excerpts of which are available online) are actually perhaps the most arresting part of Polak’s project.

For each participant, the process of seeing their journey unfold, in miniature, on the ground in front of them seems to trigger an initial bemused amazement, followed by a flood of anecdote. Mr. Idiris starts gesticulating wildly at one point, showing Polak and her translator where he had to go round in circles for hours looking for a lost cow. Binta, his sister-in-law, explains why she chose to go to the fruit market in Kubwa to sell her nonno, rather than the one in Dutse.

IMAGE: Mr. Idiris describes his rainy season route (photo from Polak’s blog).

IMAGE: Mr. Idiris explains how he lost a cow and had to spend days searching for it (photo from Polak’s blog).

Usman watches the robot perform his route with some truck driver friends — all university graduates. Initially somewhat baffled, they quickly start comparing notes about how they pass the time on the road, and which rest stops to avoid for fear of being robbed. At one point, the robot stops moving, and Polak wonders if it is broken — but then Usman remembers that he was stuck in a traffic jam for several hours, due to a fire in an overturned oil tanker.

IMAGE: Usman and Polak discuss his route (photo from Polak’s blog).

IMAGE: Lagos traffic on the Peak milk route (photo from Polak’s blog).

IMAGE: Car accident on the Peak route (photo from Polak’s blog).

Similarly, when Mr. Idiris describes his migration to the wet season pasturage, he explains that he initially headed north to Kaduna, even though he had heard something about a religious crisis there on the radio. Half way there, he met some other Fulani people who explained the danger was real, which caused an abrupt change in course.

IMAGE: Mr. Idiris explains a decision to migrate his herd to a new location, in order to avoid a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak (photo from Polak’s blog).

The robot tracks are thus both personal and systemic, capturing fluctuating ground conditions and individual decision-making processes, as well as the underlying mobilities of the two dairy economies.

IMAGE: Binta watches as her route is recreated (photo from Polak’s blog).

IMAGE: At the Peak milk depot, Usman and friends discuss their journeys (photo from Polak’s blog).

IMAGE: Usman and Mr. Idiris and family watch video footage of themselves narrating their routes (photo from Polak’s blog).

Bizarrely, Polak’s mapped juxtaposition of the traditional nomadic mobility of the Fulani with Peak’s globalised mobility has the effect of making the two economies seem more connected than their very different physical reality — cows and traditional dress versus shipping tankers and traffic — would otherwise suggest.

During their video-narratives, Usman starts talking about the health benefits of nonno, especially the nonno of your home village, while Binta tells Polak that she likes the rich and creamy flavour of Peak milk. A project that seemed as though it was all about contrasting two competing dairy economies — traditional versus industrial — actually ends up communicating the intensely personal spatial experiences embedded in each drop of milk, however it was produced.

[NOTE: Thanks to Dechen Pemba of the excellent blog High Peaks Pure Earth (one of the only places on the internet to read Tibetan commentary from within China, in translation) for the tip. Esther Polak’s earlier work, tracing milk produced in Latvia as it journeys across the E.U., is also worth checking out.]