Dogs still occupy a variety of roles in the human food system, from sheep herding to barbecued delicacy. What is less well known is that before the advent of gas or electric ovens, dogs also provided a convenient power source for kitchen appliances.

IMAGE: A doggy treadmill, yours for only $639, via Rachel Laudan.

Inspired by a contemporary advertisement for a doggy treadmill, food historian Rachel Laudan has posted some fantastic historical images of dog-powered butter churns (offered in the Sears catalogue as recently as the early twentieth-century), as well as the special, now extinct, breed of dog employed to turn meat in front of the fire in kitchens from Tudor to Victorian times.

IMAGE: “If you keep a dog, make him ‘work his passage.'” A dog-powered butter churn advertised in a Sears catalogue from the early twentieth-century, via Rachel Laudan.

According to Ivan Day, whose collection of antique British cooking equipment is unsurpassed, spit-roasting beef in front of an open hearth is “the finest technique ever devised for cooking meat.” Bee Wilson, describing the process in her excellent new book, Consider the Fork, explains that a true roast cooks slowly over several hours:

The food cooks at a significant distance from the embers, rotating all the while. The rotation means that the heat cannot accumulate too much on any single spot: no scorching. […] Both the flavours and textures were out-of-this-world superb.

IMAGE: Sirloin of beef roasting in front of a contemporary hearth, via Food History Jottings.

To roast effectively, a cook needed to find the sweet spot — the optimum distance from the fire for roasting without charring — and make sure the food was firmly attached in order to rotate with the spit. Beyond those concerns, Wilson writes, “there was one more challenge facing the roaster, and it was the trickiest by far: how to keep a hulking piece of meat in perpetual motion for the hours it needed to cook.”

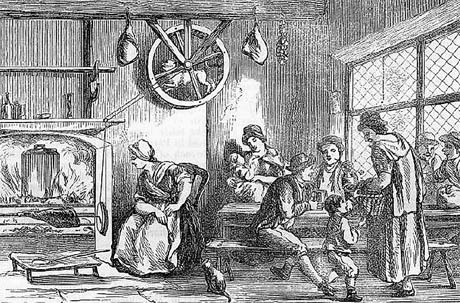

Originally, Wilson writes, the job of turnspit was usually assigned to a luckless boy, occasionally as young as five years old, who frequently worked naked or semi-clothed due to the heat. She gives the example of John Macdonald, a Scottish orphan who was demoted from his first job rocking a baby’s cradle to become a turnspit in a gentleman’s home, before rising up through the ranks to become a footman.

However, “over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Britain,” Wilson notes that boys had gradually been replaced by animals — primarily dogs, although apparently some cooks preferred to use geese, crediting them with greater stamina and less (troublesome) intelligence.

IMAGE: The Turnspit dog, from Reverend J. G. Wood’s Illustrated Natural History, published in 1853, via Wikipedia.

The existence of a special dog bred for kitchen service was mentioned as early as 1576, in an English book on dogs. According to the BBC, the turnspit was recognised by taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus as a separate breed in 1756. Based on contemporary references, it was a terrier of some sort, developed from badger-hunting dogs.

Turnspits were long in the body, like a sausage dog, with droopy ears and short, strong legs that Darwin remarked upon as an example of a desirable genetic trait nurtured through selective breeding.

IMAGE: A turnspit dog at work, in an illustration from c. 1800, via Wikipedia.

“Stuck in a wheel around 2.5 feet in diameter, suspended high up against a wall near the fireplace,” writes Wilson, turnspit dogs “were forced to trundle round and round. The treadmill was connected to the spit via a pulley.”

Abergavenny Museum claims to have “the last surviving specimen of a turnspit dog, albeit stuffed,” in its collection. However, Wilson reports that “dog wheels were still being used in American restaurant kitchens well into the nineteenth century,” when, in the face of early animal rights lobbying, they were often replaced with young black children.

IMAGE: Whiskey, the last turnspit dog, is item A.193.0 in the Abergavenny Museum collection.

IMAGE: Abergavenny Museum’s collection also includes this example of an eighteenth-century turnspit dog wheel, from Coed Cernyw, Monmouthshire.

“In the end,” she writes, “it was not kindness that ended the era of the turnspit dog but mechanisation.” Clockwork, steam, and dynamo-driven spit-jacks were “the gleaming espresso machines of their day: the single kitchen product on which the most complex engineering was lavished.”

Over the years, then, technological advances led to the turnspit breed dying out, and the spit and range itself eventually became obsolete, replaced by the electric or gas oven of today. “The small electric motor,” concludes Rachel Laudan, “is a much better way to dispose of all those time-consuming, tedious, and tiring kitchen chores assigned to women, servants, or dogs in the past.”

IMAGE: Another fantastic illustration from Rachel Laudan’s post: Nicholas Potter’s “Enterprise Dog Power” Treadmill (1881) for powering butter churns.

But, given the United States’ current canine obesity epidemic, a carbon-neutral, Brooklyn-based, artisanal, raw milk butter-churning co-op, running entirely on pet power, surely cannot be far away…

[NOTE: Apologies and thanks are due to Patrick M. James, who first alerted me to the existence of turnspit dogs a couple of years ago — and who I didn’t believe, even after Wikipedia corroborated his story!]