Call off the search for the new kale: we’ve found it, and it’s called kelp! In this episode of Gastropod, we explore the science behind the new wave of seaweed farms springing up off the New England coast, and discover seaweed’s starring role in the peopling of the Americas.

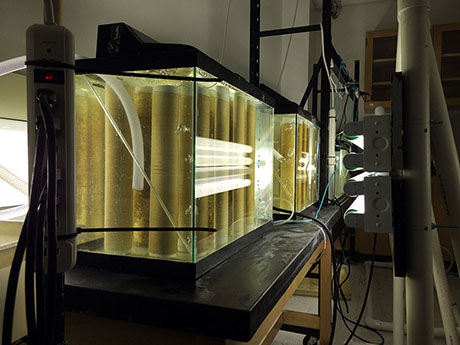

Charles Yarish’s seaweed lab at the University of Connecticut, Stamford.

The story of seaweed will take us from a medicine hut in southern Chile to a high-tech seaweed nursery in Stamford, Connecticut, and from biofuels to beer, as we discover the surprising history and bright future of marine vegetables. Along the way, we uncover the role kelp can play in supporting U.S. fishermen, cleaning up coastal waters, and even helping make salmon farms more sustainable.

D. J. King’s crew haul up the kelp line, attached to a buoy.

Seaweed growing in Charles Yarish’s lab.

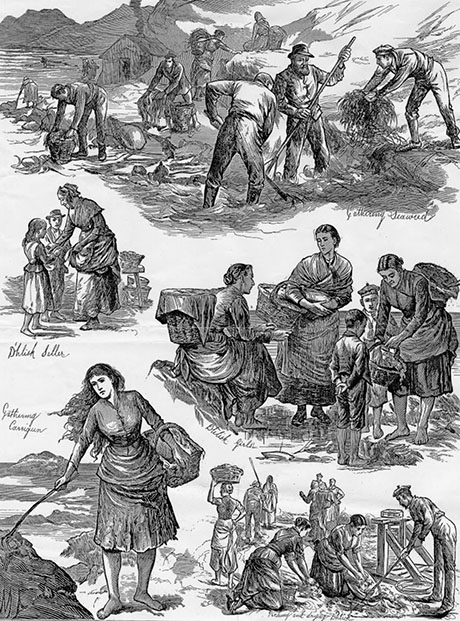

As a wild food, foraged from the rock cliffs and littoral strand of the world’s coastlines, seaweed has been an important food, fuel, and fertilizer since ancient times. In Japan, seaweed was such an crucial part of the diet that legislation in AD 703 confirmed the right of the Japanese to pay their taxes to the Emperor in kelp form. According to Scottish kelp scientist Iona Campbell, traces of it have been found in Orkney island cremation sites dating back to the Bronze Age. Even further back in history, archaeozoologist Ingrid Mainland has confirmed that the use of seaweed as a fodder for sheep in the Orkneys, which still continues today, dates to the Neolithic period, roughly 5,000 years ago.

“Irish Distress: gathering seaweed for food on the coast of Clare,” from the Illustrated London News, May 12, 1883.

Surprisingly, scientists have found even older seaweed remains in the Americas, from 12,500 years ago. Five chewed cuds of Gigartina, a red seaweed, mixed with Boldo leaves, a medicinal herb and mild hallucinogen, were found on the floor of a medicine hut at Monte Verde, Chile—one of the oldest human habitation sites in the Americas. In the episode, Jack Rossen, the archaeobotanist who excavated the site’s fragile plant remains using dental picks, explained how the site’s age and location, combined with the four different species of seaweed found in the medicine hut and in residential areas, led to the development of an entirely new theory to explain how humans arrived in North America.

Rossen also pointed out that the Monte Verde findings led to a re-evaluation of the importance of plants in the diet of hunter-gatherers—and thus also of the role of women in those early human communities.

We’ve always had the stereotype of early people being hunters, big-game hunters. And now we’re thinking more that plants would have been a much more reliable resource; they just didn’t get preserved as well at most sites. And maybe archaeologists, when archaeology was dominated by men, just liked the idea of being big tough hunters, instead of wimpy plant gatherers.

As it turns out, women have also played a pivotal role in transforming kelp from wild to farmed food. Basic seaweed cultivation techniques began to be developed in Japan beginning in the mid-seventeenth century. But, despite becoming a staple food of the Japanese, the basic biology of edible seaweed species remained almost completely unknown until two centuries later, when pioneering British scientist Kathleen Drew-Baker saved the country’s nori farming industry.

Cynthia recording the sound of seaweed sex in Charles Yarish’s lab.

In 1948, a series of typhoons combined with increased pollution in coastal waters had led to a complete collapse in Japanese nori production. And because almost nothing was known about its life cycle, no one could figure out how to grow new plants from scratch to repopulate the depleted seaweed beds. The country’s nori industry ground to a halt, and many farmers lost their livelihoods.

Meanwhile, back in Manchester, Dr. Drew-Baker was studying laver, the Welsh equivalent to nori. In 1949, she published a paper in Nature outlining her discovery that a tiny algae known as Conchocelis was actually a baby nori or laver, rather than an entirely separate species, as had previously been thought. After reading her research, Japanese scientists quickly developed methods to artificially seed these tiny spores onto strings, and they rebuilt the entire nori industry along the lines under which it still operates today. Although she’s almost unknown in the U.K., Dr. Drew-Baker is known as the “Mother of the Sea” in Japan, and a special “Drew” festival is still held in her honor in Osaka every April 14.

Spools seeded with baby kelp, growing in Charles Yarish’s lab.

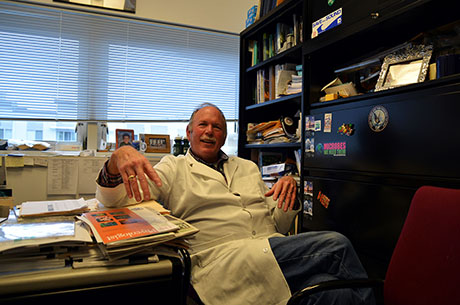

Charles Yarish in his office.

In the United States, Charles Yarish should probably be called the “Father of the Sea.” The University of Connecticut marine biologist has spent the past forty years studying the biology of seaweeds, and then applying his research to develop revolutionary new techniques for growing seaweed off the coast of North America. His innovations have helped make make kelp an economically viable crop for the fishermen and shellfish farmers of New England, whose livelihoods have been threatened by a combination of over-fishing, pollution, and warming waters.

Listen to this episode of Gastropod for a visit to Yarish’s lab to learn what he accomplished, and how seaweed farms can help soak up pollution from aquaculture, such as salmon farming, as well as from agricultural run-off and sewage. You’ll also hear how seaweed is something of a superfood; research in China has even demonstrated that it contains compounds that lower cholesterol and blood glucose levels in mice. Now the only remaining challenge is to convince Americans to eat it: Gastropod visits chef Elaine Cwynar‘s kitchen at Johnson & Wales University to sample creative new recipes.

Charles Yarish’s seaweed nursery.

This is the last episode of the first season of Gastropod. Co-host Cynthia Graber and I will be back with more food- and farming-related stories explored through the lens of science and history in the New Year. Thank you for listening!