Roadkill cuisine has been making headlines this spring, after the Montana House of Representatives passed a bill (by 99 votes to 1) that allows the state’s motorists to collect and eat the deer, elk, moose, or antelope that was unlucky enough to get in their way. Apparently, food banks in the state already collect freshly killed wild animals from the highways, clean and dress them, and distribute them to the poor, so Montana HB247 simply legalises common practice.

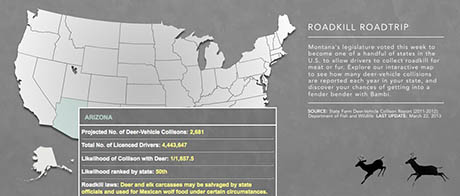

IMAGE: Screengrab from Marketplace’s interactive roadkill map. In Arizona, the state with the lowest probability of a deer/car collision, “deer and elk carcasses may be salvaged by state officials and used for Mexican wolf food under certain circumstances.”

As demonstrated by an interactive map created by Marketplace, several states already have similar laws on the books. Florida is the most permissive: according to Marketplace, “If you hit a deer, it’s legal to take it home and do whatever you want with it. You don’t need permission.”

Most states with roadkill bills do require drivers to notify the authorities; for example, in New York state, residents can salvage deer, moose, or bear from the highway, but only if the collision is reported and deemed to be accidental. A handful of other states expressly forbid the collection and consumption of roadkill, including, somewhat counter-intuitively, that well-known home of guns, “freedom,” and feral hogs, Texas.

In some rural counties in Alaska and Vermont, you can even add your name and number to roadkill phone trees: the state game warden will give you a call when there’s a fresh moose or deer “that’s not too smooshed.”

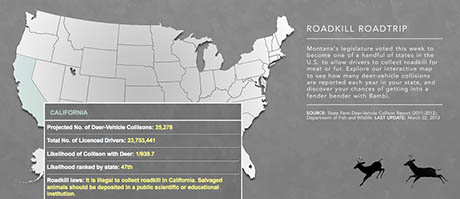

IMAGE: Screengrab from Marketplace’s interactive roadkill map. In West Virgina, the state in which a deer/vehicle collision is most likely, there are an estimated 30,203 of them each year. “If you report the fatality within 12 hours, it’s legal to remove and consume any and all roadkill. There’s even an annual roadkill cook-off.”

IMAGE: Screengrab from Marketplace’s interactive roadkill map. “It is illegal to collect roadkill in California. Salvaged animals should be deposited in a public scientific or educational institution.”

Opinions are sharply divided as to the desirability of eating roadkill.

PETA endorses it, saying that, “If people must eat animal carcasses, roadkill is a superior option to the neatly shrink-wrapped plastic packages of meat in the supermarket.” Fans point out that, as an alternative protein source, roadkill is free, naturally lean, raised without the energy and chemical-intensive inputs of farmed livestock, and avoids waste (though this last point seems moot, as there are several other species that are only too happy to dine on the flattened fauna that humans leave in their wake).

IMAGE: Opossum in Kansas City; photograph by Richard via Wikipedia.

As far as taste goes, Alaskan roadkill aficionados describe moose as “like hamburger, but with more flavour,” and savour the animal’s gelatinous nose, while British conservationist and regular roadkill consumer Jonathan McGowan sang the praises of the UK’s squashed birds and mammals to The Ecologist magazine last year:

I’m a sucker for deer and pheasant though, and I love fox. It’s delicious – like a very lean, sweet tasting pork. Similar to rat actually.

IMAGE: A moose crossing a road in Alaska; photograph by John J. Mosesso via Wikipedia.

However, not everyone is convinced. Critics point to the parasites and worms harboured by wild animals, and even fans admit to finding roadkill more appetising in the winter, when the cold acts as a natural refrigerant, halting decay. And, although pounding chicken or veal cutlets flat before cooking is a well-established technique in the French culinary canon, Marketplace reports that flattening an animal as you kill it does not produce such delicious results:

A deer that’s been slammed by a car might not have all that much edible meat. “Blood will go into that muscle and that meat is no good,” says Nick Bennett, who owns Montana Mobile Meats and processes wild game. Just how much meat you can get out of the roadkill depends on exactly where and how hard you hit it.

IMAGE: Deer near a deer crossing sign, Massachusetts; photo via The Sun Chronicle.

One of the more interesting aspects of the media coverage is discovering just how common car-animal collisions are. A spokeswoman for insurance company State Farm told Marketplace that they estimate “one and a quarter million drivers every year have some sort of altercation with a deer while in their car” in the United States. The Ecologist reports that “The Mammal Society estimates that some 100,000 foxes, 50,000 badgers and between 30,000 and 50,000 deer are killed on UK roads every year.”

IMAGE: Roadkilled deer on Route 170, South Carolina; photo by John O’Neill via Wikipedia.

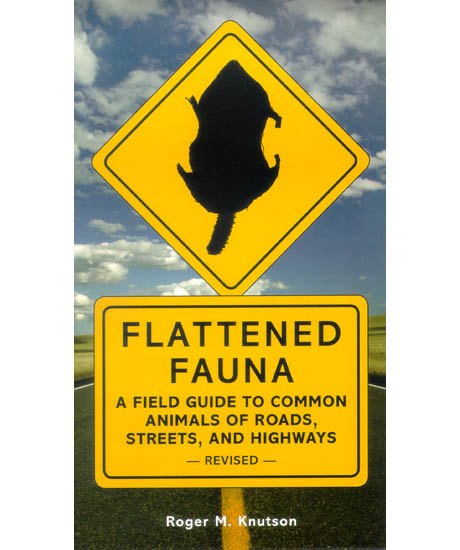

For retired biology professor Roger M. Knutson, the Michigan-based founder of the International Simmons Society for the study of flattened fauna, this ubiquity speaks to roadkill’s larger importance. In his book, Flattened Fauna: A Field Guide to Common Animals of Roads, Streets, and Highways, he notes that “those (up to now) non-descript spots and blotches of fur, feathers, and scales are the wildlife we see most often, yet nowhere has there been a guide to their identification.”

Knutson’s approach to the thirty-six most common North American roadkill specimens is that of a naturalist (albeit one with his tongue firmly in cheek), rather than a gourmet. As more and more people live in cities and biodiversity shrinks, squashed animals seem to be bucking the trend, rising in numbers — although, as Knutson laments, both historical and current data on roadkill is thin:

At a time when the total world fauna is surely shrinking in both absolute numbers and species complexity, the road fauna is clearly increasing. Before 1900, in the United States, its presence was recorded by only the most fragmentary references to the occasional horse-stomped snake. With the development in the twentieth century of a much elongated road network and dramatically increased traffic speed, the flattened fauna has increased in both species and total numbers.

Knutson cites an early count, in the “1938 classic, Feathers and Fur on the Turnpike,” in which New Englander James Simmons (in whose honour the Simmons Society is named) measured a density of 0.429 dead organisms per mile. A more recent study in Nebraska suggests that roadkill density may since have risen to 4.10 animals per mile. “This means,” Knutson notes, “that a trip of 1,000 miles could be the occasion for seeing, identifying, and even enjoying anywhere from 400 to 4,000 animals.”

IMAGE: The cover of Roger Knutson’s Flattened Fauna, “the definitive guide for the millions of people who seldom see a wild animal that has not been flattened by the dozens of vehicles ahead of them, and baked by the sun to an indistinct fur-, scale-, or feather-covered patty.”

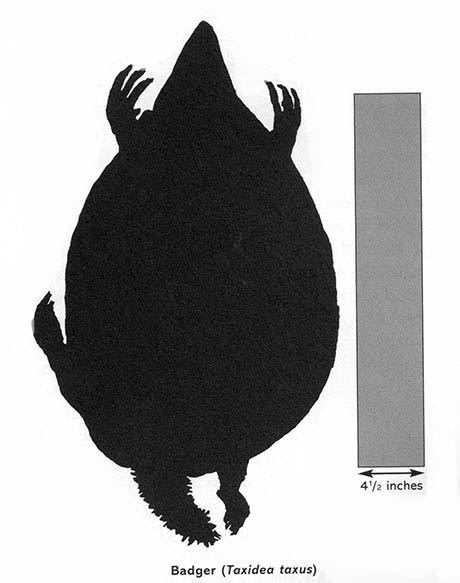

An extremely slim paperback, Flattened Fauna is nonetheless full of gems: Knutson’s sense of humour belies his detailed study of the “remarkable persistence” of muskrats on even the busiest motorways, the unfortunate tendency of cold-blooded snakes to seek large, flat, sun-warmed surfaces at night, and the particular silhouette or “form toward which” each different animal tends, in its two-dimensional afterlife (“genuine dorsi-ventral flattening is uncommon for rabbits,” for example). Indeed, the study of roadkill has a serious use, beyond entertainment value: as biologist Bob Brockie explained to Radio New Zealand’s This Way Up programme a couple of years ago, counting squashed animals on the road provides an excellent guide to shifts in population numbers and migration patterns.

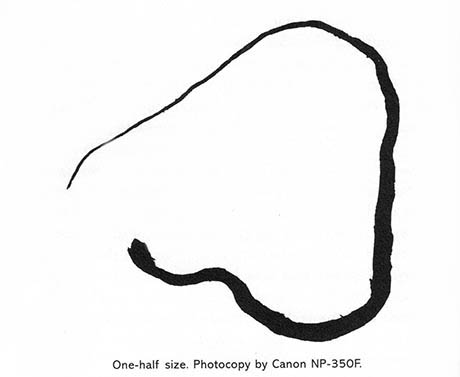

IMAGE: “The challenge,” writes Knutson, “is to distinguish snakes as a group from any of the numerous long, narrow, non-animal objects that litter the highway.” This photocopy, provided in his book, “represents most of the critical features of road snakes,” including its taper and curve (the result of a reflex action). From Flattened Fauna.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of both roadkill cuisine and roadkill safaris, however, is what it tells us about the car’s influence on our changing relationship with animals. In Flattened Fauna, Knutsen speculates that “if the road habitat and its major selective pressure — fast-moving vehicles — were to persist,” we might expect to see the emergence of characteristics related to successful highway negotiation. Indeed, though with a certain degree of scepticism, Knutsen quotes Victor B. Sheffer, author of Spires of Form, Glimpses of Evolution, who believes that “hedgehogs have learned genetically, within our century, to run from approaching automobiles instead of curling up in the defensive posture of their pre-auto ancestors.”

As for humans, as Knutson notes, many of us will drive at least two hundred miles, passing anything from five to twenty-five squashed animals, for every mile we walk in the natural world, observing live animals. Given our lifestyles, it seems only logical that we learn to extend our appreciation of animals to their two-dimensional forms — with, of course, the help of his book, “which is devoted to making the experience of seeing dead animals on the road meaningful, even enjoyable.”

IMAGE: The badger, “the largest, flattest creature to be found on the road,” is here compared to a standard road marking for ease of identification. From Flattened Fauna.

Meanwhile, having domesticated both ourselves and our food supply, we could perhaps argue that the underground popularity of roadkill cuisine is a technologically enhanced resurgence of our inner hunter-gatherers — even if the hunting is being done, for the most part, from the leather seats of a four-wheel drive. Although Montana’s new law has apparently been written to discourage intentional collisions, examples have been reported of roadkill poachers, who, rather than using a bow and arrow or gun, simply put a jam sandwich or sausage roll on the road as bait, and then lie low waiting for a passing vehicle to kill their dinner for them.

Hours of study have been devoted to understanding the ways in which cars have reshaped the built environment, our perception of space and time, and even the global atmosphere; perhaps roadkill provides a small, easily overlooked example of some of the ways they have also redesigned our relationship with the animal world?