The maple syrup season was late this year, and so am I in posting these images of a late March visit to two sugar-making operations in the Hudson Valley.

The first sugar shack we visited, Soukup Farms in Dover Plains, NY, is a third-generation maple producer with an old-school, wood-fired sap evaporator.

IMAGE: The sugar shack at Soukup Farms. All photographs by Nicola Twilley.

IMAGE: Loading firewood into the evaporator at Soukup Farms.

I asked them if they were burning maple wood, and received a horrified stare in response: this is not cannibal syrup.

The small shed was a maple sauna: a toasty, fairy-tale fug of sweet steam above a faint note of wood smoke. At the tail-end of a long, hard winter, with the snow still lingering stubbornly on the ground, it was hard to imagine a better place to be.

IMAGE: A maple cloud above the evaporator at Soukup Farms.

Having inhaled brunch, we set off down the road to visit Soukup’s more high-tech neighbour, Madava Farms.

IMAGE: Barrels of maple syrup in cold storage at Madava Farms.

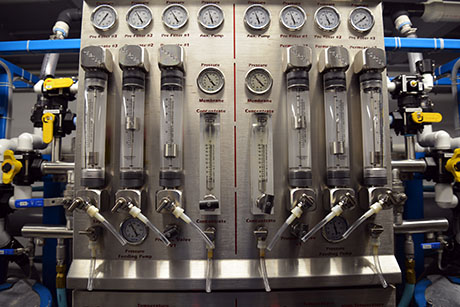

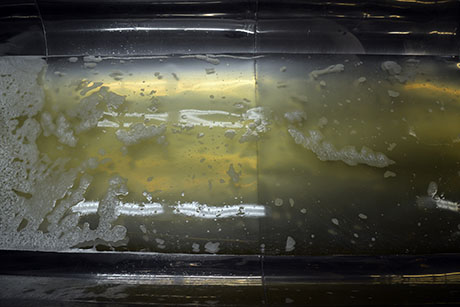

One of the largest maple syrup producers in the country, Madava Farms’ sugarhouse is more ski resort-chic than rustic shack. But what it lost in atmosphere, it made up for in spectacle: the green, foamy sap, like diluted dish soap, filling the collection tanks; the spaceship-worthy shiny dials and levers of the reverse-osmosis machine; and the gelatinous, sickly chartreuse of the resulting pre-boil syrup.

IMAGE: Sap collection tank at Madava Farms.

IMAGE: Reverse-osmosis machine at Madava Farms.

IMAGE: The concentrated sap, after reverse-osmosis but before boiling.

Maple syrup is simply the concentrated form of maple sap, with the water boiled off or separated by membrane suction. It takes between 40 and 50 gallons of sap to make a gallon of syrup, though the sap is also increasingly pasteurised and bottled for sale as “maple water.”

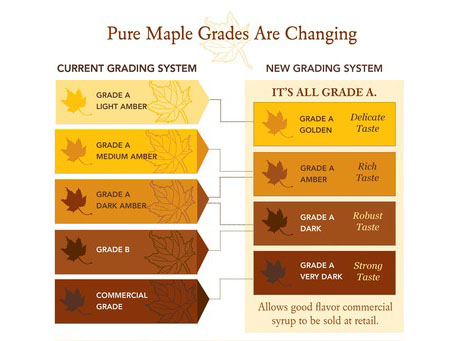

Reverse-osmosis and maple water are just two of the many ways the traditional maple business is changing. Last year, the International Maple Syrup Institute released a new set of standards for syrup grading, although adoption has been slow.

Maple syrup grades reflect the amount of sugar in the sap, which varies over the course of the season. Sap that is 2 percent sugar and 98 percent water will be lighter in colour by the time it has been concentrated to 66 percent than sap that starts off at 1 percent, because the sugar will be less caramelised. On the other hand, the hundreds of trace compounds that give maple its flavour will also be more concentrated in the darker syrup.

Traditionally, the lighter, more delicate-flavoured syrup was sold as Grade A Light Amber, while the darker stuff was confusingly classified as Grade B, implying to the average consumer that it was of lesser quality, despite actually having more maple flavour.

IMAGE: Traditional USDA colour standards for maple syrup, ranging from Grade A Light Amber on the left to Commercial Grade on the right, as seen in the window of Soukup Farm’s sugar shack.

IMAGE: A label created by Butternut Mountain Farm in Vermont explains the difference between the old and new grading systems, via.

In keeping with our current cultural tendency toward grade inflation, under the new system, everything gets an A.

Grade A Light Amber becomes Grade A Golden (Delicate Taste) while Grade B becomes Grade A Dark (Robust Taste). The new system doesn’t go into effect in New York State until January 1, 2015, so we bought one of the last bottles of Grade A Dark Amber.

IMAGE: Tapped trees at Madava Farms.

Madava Farms also allows visitors to wander through its maple forest, which is a truly astonishing sight: more than 20,000 maple trees plumbed together into one sprawling vascular system, with miles of blue and green plastic tubing gleaming like spider silk in the late afternoon sun.

IMAGE: Tubing lines catch the light at Madava Farms.

Plastic tubing began to replace the traditional bucket and tap system in the 1960s: rather than simply wait for sap to spill out of its own accord, the airtight tubing connects each tree to a whirring vacuum pump, sucking the sugary water up under pressure.

The maple forest becomes a super-organism, as each tree’s internal plumbing is connected to a larger, landscape-scale hydraulic infrastructure.

IMAGE: The tubes converge into larger, black rubber pipes…

IMAGE: … that flow into the to the collection house.

The trail ends at the collection house, where thousands of miles of artificial tree veins converge on the motorised heart at the centre of the system, sap spurting rhythmically into a stainless steel tank.

It is a sight that couldn’t be further from the rustic warmth of Soukup Farms, but has a chilling, post-natural wonder all of its own.

IMAGE: The vacuum pump at the heart of Madava Farms’ maple forest plumbing.

Although purists complain about this new “techno-syrup,” researchers at the University of Vermont’s Proctor Maple Research Center say that the vacuum tubing collection increases yield without damaging the tree. It seems as if it would be labour-saving, too—the maple farmer no longer has to collect each bucket individually—but installing thousands of miles of plastic tubing each January and keeping it leak-free (squirrels are a particular pest) takes a full-time team of half a dozen specialists at Madava Farms.

Technology aside, the entire phenomenon of maple syrup is semi-miraculous: a physiologically unique phenomenon in which sap flows independent of the usual leaf transpiration or root pressure mechanisms. Instead, in a complicated and only recently understood process, freezing temperatures at night create ice in the maple tree’s xylem, trapping gas in the vessels through which the plant normally transports water. When the ice melts in the heat of the day, the gases expand, creating the positive pressure that propels sap up the xylem, and—if the tree is tapped—out.

Weirdly, almost all other tree species lack this mechanism. Several species (willow, aspen, elm, ash, and oak) don’t exude sap at all, due to differences in the structure of their xylem. Other syrup-producing tree species, such as birch, rely on a build-up of root pressure from warming forest soil, which makes the birch sap season later than that of the maple.

Sadly for New England forest lovers and pancake aficionados alike, climate change is disrupting the spring cycle of freezing nights and warmer days upon which the maple syrup industry depends. After all, one anomalous extended warm spell can cut the season short, as the trees bud. Similarly, as happened this year, an unusually long cold snap can eat into the start of the spring run.

The University of Vermont’s scientists think they have developed a system to sidestep global warming’s worst implications, but it involves harvesting sap from uniform rows of beheaded saplings rather than mature trees, looped together into a hydraulic forest. I recommend appreciating this peculiar form of infrastructural magic while you still can.