IMAGE: A city on a trike, Worksman Cycles, Queens, New York (all photos by Nicola Twilley unless otherwise noted).

The oldest bike manufacturer in the U.S., Worksman Cycles, also happens to be the home of two American food vending icons: the Good Humor ice cream tricycle and the New York City hot dog cart. What’s more, if you live in New York city, chances are that your last delivery pizza or egg roll traveled to your door in the front basket of a Worksman bike, and if, instead, you live in the Connecticut suburbs, you may well have enjoyed a cold Bud purchased from a Worksman-made drinks trolley during your evening Metro-North commute.

IMAGE: Shaping metal components by eye.

I recently visited Worksman with a class of students from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, as part of a studio that Geoff Manaugh of BLDGBLOG and I are teaching this spring called “The City of Mobile Services.” It’s a topic I’ve been researching (and muttering about putting together some sort of pamphlet about) since 2008, when the food truck trend was just getting going. I spent a day with a bookmobile in London, with the Grow Truck mobile tool-share service in New York City, and with Let’s Be Frank, a gourmet hot-dog stand that rolls around the westside of Los Angeles, and I became increasingly interested in the way these mobile services reconfigured the static physical, economic, and edible geography of the city.

IMAGE: A typical food cart in action in New York City, complete with pigeon.

Meanwhile, at both Foodprint NYC and Toronto, Sarah Rich and I found ourselves talking about food carts, as a fascinating case-study of the way economic and regulatory forces play out at the street level to shape an urban, mobile food delivery system.

IMAGE: The factory windows are tinted a rather lovely blue, a legacy of its wax-handling past.

Located in a former birthday candle factory in Ozone Park, Queens, Worksman Cycles’s bread-and-butter business is actually the heavy-duty front- or rear-loading trikes used by companies such as Boeing or Exxon to move parts back and forth along their vast production lines. In fact, one of Worksman’s industrial tricycles had a cameo roll-on in a Hyundai ad during this year’s Super Bowl.

IMAGE: A Worksman Cycle industrial tricycle, painted yellow for visibility on the factory floor, gets a cameo during Hyundai’s Super Bowl advertisement.

The solid construction that equips a tricycle to haul engine parts around a factory floor happens to also be ideally suited to the rigours of selling hot-dogs in New York City’s mean streets — indeed, Worksman’s Bruce Weinreb told us that their carts frequently emerge from collisions in better shape than the car or lorry that hit them.

IMAGE: Bruce Weinreb demonstrates the thickness of a Worksman wheel rim, one of the only cart elements that is not manufactured from scratch on site. Behind him, a worker is inserting thirty-six spokes into a wheel rim, four at a time.

Worksman was founded in 1898, by Morris Worksman, an immigrant with a shop in what subsequently became the footprint of the World Trade Center, amidst the horse-drawn congestion of Lower Manhattan. He became convinced that tricycles (which, like their wheeled cousin, the car, were still a relatively new invention at the time) would make an excellent urban replacement for horses: longer-lasting, less expensive to maintain, and completely emissions free (as opposed to the 2.5 million pounds of manure New York City’s horses produced, per day, in 1900 — an escalating crisis that, according to delegates at the city’s first urban planning conference in 1898, meant that the city’s streets would soon be nine-feet deep in the stuff).

IMAGE: The original ice cream cart, designed by Worksman in collaboration with Good Humor. Photo via the Worksman website.

Morris began creating wheeled vending and delivery carts for local merchants, inventing a new gear system for Harley Davidson motorcycles along the way. The company struck design gold in the 1930s, however, when the newly formed Good Humor ice cream company came up with the idea of distributing its products on tricycles equipped with sleigh bells. Schwinn, a slightly older and larger bicycle company (still in operation, but no longer manufacturing in America) turned down the business, but referred Good Humor to Worksman, who developed the iconic front-load ice-cream tricycle, complete with dry-ice shelf and specially tuned chime bells, and still manufacture it today.

IMAGE: Worksman still sells these “Good Humor-Style Brass Tuned Ice Cream Chime Bells for Ice Cream Sales” for $79. Photo via the Worksman website.

IMAGE: Ice-cream cart boxes at the Worksman factory. The traditional front-load dry ice ice-cream tricycle costs $2,149 new, and, Bruce assured us, will more than pay for itself over a hot summer’s vending.

Worksman cannot claim design credit for its other contribution to the mobile food landscape of America: the classic diamond-patterned stainless steel New York City hot dog cart was developed by Ed Beller in the 1940s, based on the form of earlier wooden hot Frankfurter push carts. Beller bought the wheels for his umbrella-topped stainless steel boxes from his Lower Manhattan neighbour, Morris Worksman, and, in 1996, Worksman acquired Beller’s company (called Admar) and brought its production in-house.

IMAGE: This photograph from 1910 shows a wooden New York hot-dog cart. Despite the difference in material, the cart has much the same form as its contemporary stainless steel descendants. Photo: Brown Brothers via The New York Times.

IMAGE: Admar’s first stainless steel hot-dog carts, photo via Worksman.

IMAGE: A row of classic Worksman hot dog carts on the factory floor.

A basic hot dog cart, with a sterno heater rather than propane, costs less than $4,000, and can be ready in ten weeks from order. For generations of immigrants, a push cart has represented the first micro-entrepreneurial rung on the ladder to a better life — famously, Goldman Sachs and Bloomingdale’s both began as street vending businesses. Hot-dog cart vending is largely a Bangladeshi trade now, with some Dominicans, having been dominated by Egyptians in the seventies. Manufacturing the carts is also an immigrant business: Bruce told us that when he joined Worksman, the welders were all Greek — former employees of Aristotle Onassis’ shipyards — whereas now they are majority Indo-Caribbean.

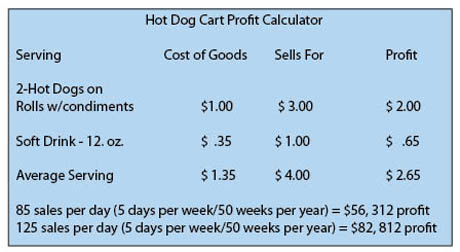

IMAGE: Worksman’s hot-dog profit calculator.

As if immigrant entrepreneurship was not all-American enough, Worksman goes a step further by keeping its manufacturing in New York, and sourcing almost all of its raw materials from the U.S., making it unique in both the bicycle and vending cart businesses. In 1900, ten million bikes were made in the U.S., whereas this year, American bike sales are projected at between twelve and thirteen million, but domestic production will not exceed 10,000 — most of which are made in Queens, at Worksman.

IMAGE: City of Mobile Services student George models a sushi delivery bike.

IMAGE: An American flag hangs on the factory floor, behind two Metro-North drinks trolleys in for refurbishment.

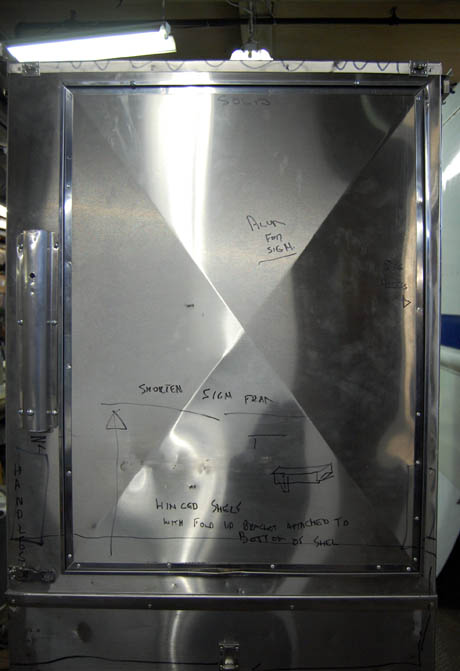

Evolution in the design of mobile food units is slow, in part because of the restrictive public health prescriptions that define “sanitary construction” in the Rules of the City of New York. These outline specific overall dimensions, as well as minimum sink capacity, acceptable food coverings, venting requirements, and more. Even when variation is allowed — for example, the city agrees that carts can be made of something other than stainless steel, providing it is “approved by the department, impermeable, readily cleaned and resistant to scratches and dents” — most cart purchasers seem to think it is not a risk worth taking.

IMAGE: This machine stamps sheets of stainless steel with the traditional diamond pattern favoured by New York City’s food cart vendors.

IMAGE: This hot-dog cart is more expensive than the classic model, but offers much-needed protection from the elements.

IMAGE: Applying the finishing touches to a kebab cart.

IMAGE: Welding bike frames by hand.

Everything is made to order (Worksman carries no inventory) and production is barely automated. Every single wheel is trued by hand, and every single tire is put on each of those wheels by hand. In fact, one of the biggest recent design changes Bruce could think of was to the colour of their ice-cream tricycles, which used to be the battleship grey of leftover liquid paint. Their paint guy in Brooklyn switched to powder coating, and mentioned one day that this new technology meant that Worksman could now choose any colour they liked. After much internal debate, they chose black.

IMAGE: Wheel-making is the most time-consuming and tricky part of bike manufacture.

IMAGE: One man puts tires on every wheel that Worksman produces.

There is slightly more design freedom in carts that don’t have to be “street-legal,” and Worksman makes a variety of party hot-dog and popcorn carts for resorts and the like. As more companies jump on the food cart trend, Worksman is designing high-end jelly bean carts for hotel room service (making the required adjustments for a tighter turning circle) as well pseudo-carts for one-off promotions by KFC and Kate Spade.

IMAGE: This Brooklyn Brewery bike is specially measured to hold two six-packs securely.

IMAGE: A Worksman “party cart.”

On the business end, Bruce told us that Worksman is gradually shifting away from the low-margin hot-dog cart business toward higher-end food trucks. These customers (mostly recent MBAs, reports Bruce) arrive with a second-hand truck, their own graphic designers, and an ambitious business plan, and typically pay between $40,000 to $100,000 for a rebuild that takes four to five months.

IMAGE: Omar and Chris explore the gutted interior of an Insomnia Cookies truck.

Bruce bemoaned the fact that Worksman had missed out on the cycle rickshaw market in New York, but given that they also sell power back to the grid at weekends from a solar array on the factory roof, and host signal boosters from every carrier on a tower in their courtyard, their business appears to be not only in good shape, but refreshingly diversified.

IMAGE: Worksman Cycles factory, complete with mobile phone tower.

IMAGE: A fleet of proto-trikes awaits the next step in their manufacture.

And it’s amazing to trace back New York City’s fleet of shiny steel food carts to this blue-lit, family-run, slightly ramshackle factory in Queens — a vital node in the peripheral, static infrastructure that enable the city’s mobile economy to function.

[NOTE: Thanks to Bruce Weinreb of Worksman Cycles for a wonderful tour, to my co-instructor, Geoff Manaugh, for setting up the trip, and to our students for their great questions. You can follow the studio progress online here, and my own intermittent posts on the subject will all be filled under the City of Mobile Services category.]