From inner-city food deserts to car-centric suburbs, aspects of the physical environment are frequently cited as a contributing factor to the rise of obesity in the developed world. However, new research, published earlier this year in the International Journal of Obesity and summarised online at the Public Library of Science (PLOS) blog, Obesity Panacea, found a surprising correlation between elevation and obesity in the United States.

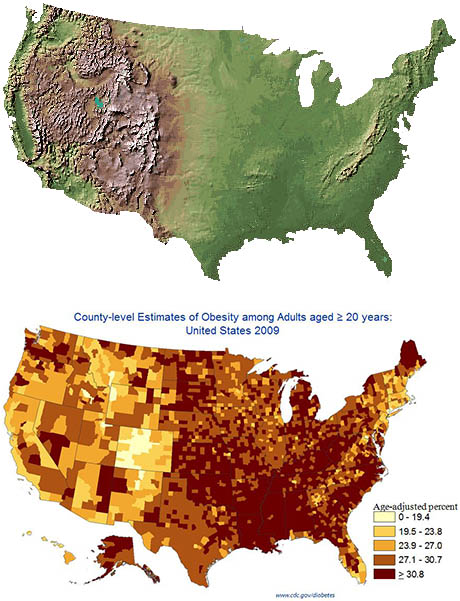

IMAGE: Above, a topographical map of the USA, from the USGS National Elevation Dataset; below, a Centers for Disease Control map showing age-adjusted obesity prevalence by county.

As the paper’s lead author, Dr. Jameson Voss of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, points out, mapping obesity prevalence in America reveals distinct, and hitherto unexplained, geographic variations:

Obesity appears most prevalent in the Southeast and Midwest states and less prevalent in the Mountain West. Despite significant research into the environmental determinants of obesity, including the built environment, the explanation for these macrogeographic differences is unclear.

Intriguingly, those areas in which less than a quarter of the population is obese map almost exactly onto the more mountainous regions of the country—the Appalachians, the Rockies, and the Sierra Nevada. And, indeed, after controlling for diet, activity level, smoking, demographics, temperature, and urbanisation, Voss and his colleagues found “a four- to five-fold increase in obesity prevalence at low altitude as compared with the highest altitude category.”

To repeat: Americans who live less than five hundred metres above sea level are more than five times as likely to be obese as their counterparts who live at or above 3,000 metres — even when diet, physical activity, and socio-economic status are all taken into account. Mountain-dwelling Americans, Voss found, weigh in a full 2.4 points lower on the Body Mass Index, on average, than their lowland compatriots.

Voss himself admits to being surprised at the magnitude of the correlation, and he cautions that correlation does not prove causation. However, he does note that a handful of other studies have also demonstrated a link between differences in elevation and body weight.

Among 617 Tibetans, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and BMI were inversely related to elevation, in a range from 1200 to 3700 m above sea level. Similarly, in an endogamous Indian population, women living in the plains were overweight, whereas those living at elevations above 2400 m were of normal weight. Similarly, dogs were found to have lower rates of obesity in the Mountain West than in lower elevation areas of the United States.

He also points out that clinical trials, in addition to observational studies, have shown that hypoxia (due to a reduced oxygen supply, as is the case at altitude) can cause weight loss. Indeed, hypoxia has been demonstrated to induce anorexia in obese rats.

The physiological mechanisms and evolutionary reasons behind this are complex and still somewhat uncertain: Voss speculates that “protection against obesity in hypoxic environments may be biologically adaptive, whereby hypoxia alters the near term survival tradeoff between the benefit of increased energy storage and the cost of excess body weight.”

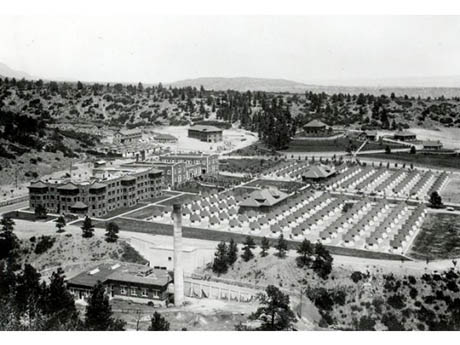

IMAGE: The Woodmen Sanitorium, complete with individual cabins shaped like teepees to maximise air circulation, Colorado Springs, Colorado. Photograph courtesy the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum, via The Colorado Springs Gazette.

Of course, this not the first time that topography has been proposed as therapy in the face of an intractable epidemic. Before the discovery of the antibiotic streptomycin, doctors used to prescribe a “mountain cure” for tubercular patients, in the hopes that an extended spell in the clean, cold air would help heal their diseased lungs. In the early twentieth-century, there were seventeen sanatoriums in the Pikes Peak region of the Rocky Mountains alone, to the extent that, in Colorado Springs, according to the director of the local history museum, “Tuberculosis was our industry.”

Given the implications of Voss’s study, it seems as though mountainous regions may be able to promote themselves as health resorts once again, luring in those for whom WeightWatchers, Atkins, and the 5:2 regime have all failed.

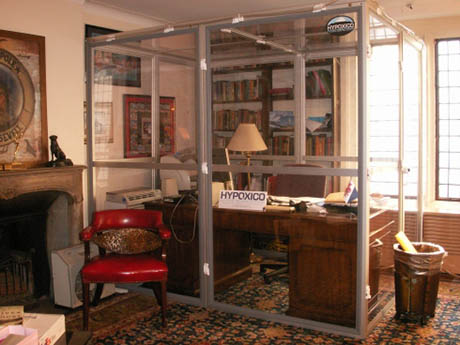

Perhaps doctors will offer their morbidly obese patients the option of relocating to Denver or Boulder, in lieu of a gastric bypass. Or, more likely, health insurers, already reeling from the burden of America’s obesity epidemic, will reimburse customers for the installation of a domestic altitude simulation chamber, such as those currently marketed to elite athletes by companies such as Hypoxico, that “allows you to work or sleep at the altitude of your choosing in the comfort of your home.” Meanwhile, during the day, a mask and wheeled hypoxic generator mean that you can bring the mountains with you.

IMAGE: An at-home Hypoxico chamber, adjustable to 3,800 metres of simulated altitude.

The virtual elevation of an entire nation: the next step in anti-obesogenic design?