Golf, with a couple of hacks, can be a surprisingly delicious-looking game.

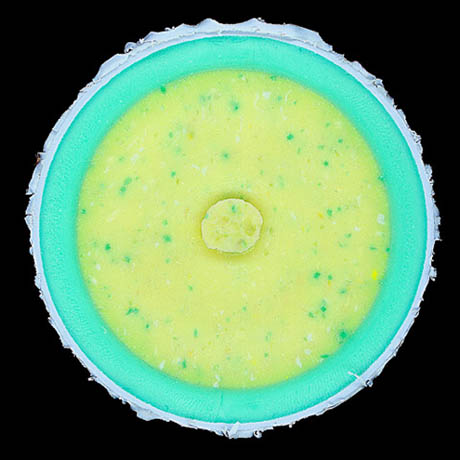

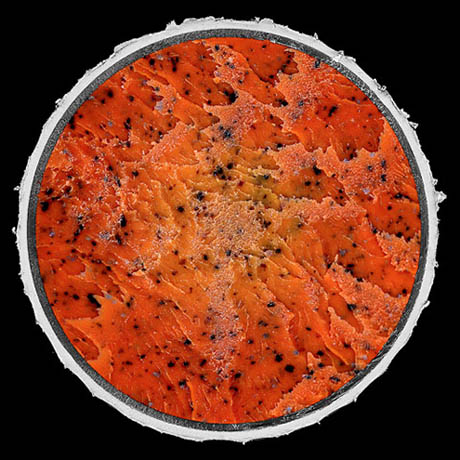

Cutting golf balls in half, for example, reveals delightfully bonbon-esque interiors.

All golf ball cross-section photographs by James Friedman.

These cross-sections are the work of Ohio-based photographer James Friedman, who does not actually play golf.

The variety of colours and flavours adds to the pick & mix effect, with watermelon gummy candies, scoops of raspberry ripple chip, and even what looks to be a sour mix gumball. Others veer into the territory of abstract art, with a surprising similarity to the colour field works of Kenneth Noland.

As it happens, the interior of at least some golf balls would seem to be edible*, with Golfsmith noting that “Titleist, for example, has used a salt water and corn syrup blend” in their liquid core balls. However, the majority of today’s golf balls have a synthetic rubber core, which, Golfsmith adds, “may be mixed with bits of metal, such as tungsten or titanium — or a plastic-like material such as acrylate.”

Not all balls are created equal: the more layers, the better, it seems. “As of 2012,” according to Golfsmith, “the most complex balls contain five pieces, including the cover.”

A ball’s internal construction is a key factor that determines which ball a golfer should choose. One-piece balls are strictly for practice. Average golfers are generally fine with two-piece balls, which are durable and will roll farther than multilayered balls. Balls of three or more pieces – which also feature softer covers – are generally for advanced players. They’re lighter and easier to spin, allowing pros and low-handicappers to stop the ball on the green, for example.

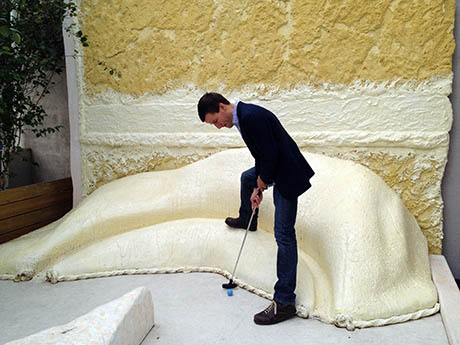

Meanwhile, last summer, jellymasters Bompas & Parr reinvented miniature golf with a sugary theme. As they point out, “novelty golf and exciting food are long time bed-fellows.” After all, El Bulli, “the world’s best restaurant,” started life as a miniature golf course.

IMAGE: I dragged Steve Twilley and Geoff Manaugh along for a round of Bompas & Parr crazy golf last summer. Photos by Nicola Twilley.

Bompas & Parr recreated cake versions of the seven wonders of London in fondant and piped icing to form a challenging nine-hole crazy golf course on the rooftop of Selfridges, in London. Complete with Bakewell-scented scorecards and a real-life tea room, the installation recreated some of the long-lost, pleasure-garden atmosphere of the 1920s and 30s Selfridges rooftop, which originally also featured a rifle range, perhaps for those suffering from post-miniature golf rage.

Curiously, Selfridge’s first rooftop miniature golf was built in 1930, as part of a massive boom in crazy golf construction following the 1929 stock market crash. According to Bompas, “as businesses collapsed, miniature golf courses sprouted across the globe, with 25,000 opening in 1930 in the U.S. alone.”

As the global economy entered the Great Depression, crazy golf’s appeal was apparently irresistable, with The Nation explaining in 1930 that:

When the pseudo-Klieg lights are playing full upon the humble householder from Hackensack, the man not only experiences that comfortable country-club feeling superinduced by drooping plus fours and prehistoric posture: he may also be able to capture the illusion that he is John Barrymore at work.

Harpers magazine, writing in the same year, reiterated the point:

Thanks to the miniature courses, every man can say that he plays golf…breaking in at last on that sport of the minor aristocracy – its appeal in a year of hard times was hard to resist.

IMAGE: Geoff conquers hole #6. Despite his triumphant air, it should be noted that I actually won the round. Photo by Nicola Twilley.

Indeed, according to Bompas, the game’s popularity was viewed as a minor economic miracle in an otherwise gloomy market, with trade journals such as Concrete and Electrical World ebullient over the quantities of materials and light required to fuel and operate this rapid proliferation of crazy golf courses.

As is perhaps unsurprising for sport whose courses are themselves a simulacra of Scotland’s glacial landscape, the resonances of golf’s equipment and its scaled-down version turn out to be curious indeed, ranging from macro-economics to novelty cuisine, via abstract art and gummy candy.

NOTE: James Friedman’s photographs of golf balls in cross-section discovered via the Manhattan User’s Guide.*DO NOT EAT THE INTERIOR OF GOLF BALLS!