IMAGE: Das Currywurstfeld, in Berlin, as seen from above.

Germany’s Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR) is the federal government agency responsible for studying and assessing food, products, and substances in terms of consumer health and safety. As such, it issues reports on nanosilver in cosmetics, determines the health risk of the cocaine content in Red Bull Simply Cola, and studies the possible dangers of shipping container fumigants.

It also dabbles in landscape design, building plant labyrinths to communicate risk:

From 28 August to 3 October, the Curried Sausage Field is open to visitors on Diedersdorfer Weg in Berlin. This is BfR’s second didactic plant labyrinth. Following on from the major success of the first one shaped like a cow in the summer of 2009, BfR extends an invitation this year to visit a 5-hectare labyrinth shaped like a curried sausage.

IMAGE: Examining an exhibit at the Deutsches Currywurst Museum. Photo by AP, via the Wall Street Journal.

Currywurst, for those who have not had the dubious pleasure, is Germany’s iconic fast-food — the equivalent of British fish and chips or the American hamburger.

It consists of fried slices of sausage (skin optional — apparently it was unavailable in the communist East), submerged under a reddish-brown sauce of ketchup or tomato paste mixed with curry powder, frequently accompanied by chips and mayonnaise. According to popular belief, it was invented in the rubble of post-war Berlin by the entrepreneurial Herta Heuwer, who lived in the British occupied sector and supplied thirsty soldiers with alcohol in return for ketchup, Worcestershire sauce, and curry powder from the NAAFI stores.

While wandering the 2.5 km of winding paths within the BfR’s Currywurstfeld, the dish is deconstructed and its component parts examined individually. Naturally, given the labyrinth’s architects, the signage pays particular attention to a variety of health hazards encountered during a currywurst’s preparation and consumption:

In the labyrinth shaped like a huge curried sausage, attention focuses on production, ingredients and preparation. Individual sections contain more detailed information about the sausages, chips, ketchup, mayonnaise, and curry powder.

What different spices are contained in curry powder? What are ketchup and mayonnaise made from? Answers to these and other questions are provided in the labyrinth. At the end, the question about how healthy the curried sausage dish is, of course, answered too.

IMAGE: Images from the BfR’s Currywurstfeld brochures and worksheets.

IMAGE: The currywurst warns against consuming raw meat on this BfR worksheet.

From what I can gather (based on these worksheets (pdf) and my GCSE German), a visitor’s exploration of the wrong turnings a currywurst can take on its journey from pig, tomato, and potato to your plastic fork is limited to pretty standard food safety lessons. At regular intervals throughout the maze, panels and interactive installations advise on the importance of handwashing, avoiding cross-contamination of cooked and raw meat, and correct storage for potatoes, tomatoes, and mayonnaise, as well as the likelihood that deep-frying your chips will create acrylamide.

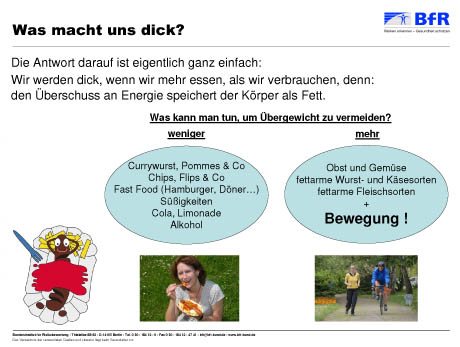

The final stop on the journey asks “What makes us fat?,” and shows an illustration of a smiling currywurst and a photo of a slim woman eating one, alongside instructions to consume less fast food in favour of more fat-free sausages and cheese, fruit and vegetables, and exercise.

IMAGE: “What makes us fat?”: the ultimate question for currywurstfeld visitors.

Last year’s didactic plant labyrinth — the RisiKuhLabyRind — was dedicated to the exploration of maize. Intriguingly, it was shaped in the form of a cow’s internal organs. However, the lessons taught were limited to the sort that could be happily endorsed by Monsanto or Archer Daniels Midland: the wealth of food and non-food products derived from corn, the need for pesticides to protect maize crops, and the miraculous transformation of corn into milk through its use as cattle feed.

IMAGE: The RisiKuhLabyRind, as seen from above.

IMAGE: Images from the RisiKuhLabyRind opening ceremonies in 2009.

The didactic plant labyrinth initiative was developed by the BfR in collaboration with the University of Kassel, as a way to use the powers of freier Natur to stimulate all our senses, making these lessons memorable “even for city children.”

It’s an interesting idea: after all, there is some research to suggest that walking the labyrinth encourages right brain activity, in addition to the common New Age and religious associations of labyrinths with mental clarity, heightened well-being, and personal transformation. Meanwhile, fans of the Edible Schoolyard initiative testify to the power of multi-sensory, garden-based lessons to reach even the most disaffected children.

IMAGE: The labyrinth at Chartres.

Nonetheless, I can’t help but be disappointed at the educational messages embedded within the labyrinth’s architecture. After all, while a labyrinth’s twists and turns do make the perfect metaphor for curry sausage and cow’s intestines, they also match the convoluted journeys our food takes within the industrial food system, and our (frequently extraordinary) distance from its source.

Didactic plant labyrinths are simply too good an idea to waste on marketing corn-fed beef or promoting handwashing, when instead they could be demonstrating the multiple pathways through which the soybean infiltrates today’s food culture, or the economic nodes and exchanges of America’s consolidated meat industry.